Chap 3 Section 3 Defining Exercise

Chap 3 Section 3 Defining Exercise

Section 2

Introduction: Defining Exercise

Learning Objectives |

|

What is the difference between physical activity and exercise?

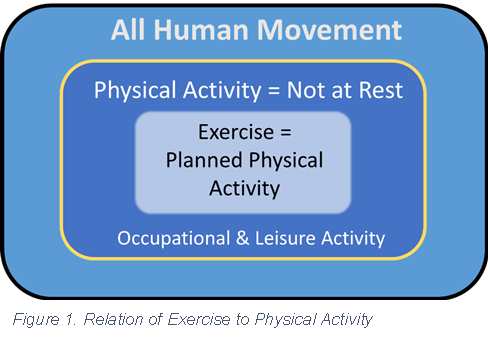

In the paragraphs above, you will find the terms “physical activity” and “exercise”. Often, these two terms are used interchangeably in public health messaging, the popular press, and social media but there are important differences. Using a “whole-and-part” relationship, exercise is a part of physical activity (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Relation of Exercise to Physical Activity

The American College of Sports Medicine (American College of Sports Medicine, 2022) provides the following definitions of physical activity and exercise:

Physical activity is “any bodily movement produced by the contraction of skeletal muscles that results in a substantial increase in caloric requirements over resting energy expenditure” (page 1).

Exercise is a type of physical activity “consisting of planned, structured, and repetitive bodily movement done to improve and/or maintain one or more components of fitness” (page 1).

To simplify, physical activity is any bodily movement made by the individual that is more than rest. In much of modern society, adults spend many hours a day in a resting or near-resting state while sitting or reclining. Exercise is a specific type of movement(s) with intentions towards a physical change. The implication here is a “workout”. The lines between physical activity and exercise can be blurry. For example, a shopper who wants to improve their health decides to park further from the grocery store entrance for a longer walk. Is this walk planned, structured, repetitive body movement with an intent to physically change? Yes, particularly if the shopper is sedentary and deconditioned. If this walk to the store is not physically demanding to the shopper, then it may be physical activity.

10,000 steps per day – what are the health benefits?

A popular message in public media is that taking 10,000 steps per day confers health benefits to adults. There is no U.S. public health recommendation for a step count threshold for health benefits, but the evidence in support of a recommendation is mounting. Interestingly, the origin of the 10,000 steps per day message may have been a marketing campaign for walking clubs in Japan, coinciding with the 1960 Tokyo Olympics. The brand name of the pedometer promoted at the time translated to ‘ten-thousand steps meter’ (Tudor-Locke & Bassett, 2004). Counting steps is appealing to the public in part because it is a simple measure of physical activity that ambulatory individuals can record and monitor using a pedometer, fitness tracker, or smartphone application. Furthermore, walking is a popular type of physical activity in the U.S., requires little equipment, and involves familiar motor skills. A step-count based goal also has limitations, most notably for persons who are not ambulatory. Side Note: fitness trackers such as the Apple Watch do not reliably measure physical activity for persons who use a wheelchair (Glasheen et al., 2021) and better solutions for this population are needed.

In the clinical encounter, it’s more important for the nurse practitioner to emphasize the importance of physical activity for health and less important to decide whether the patient describes physical activity or exercise. |

Bottom line: patients should avoid being physically inactive. |

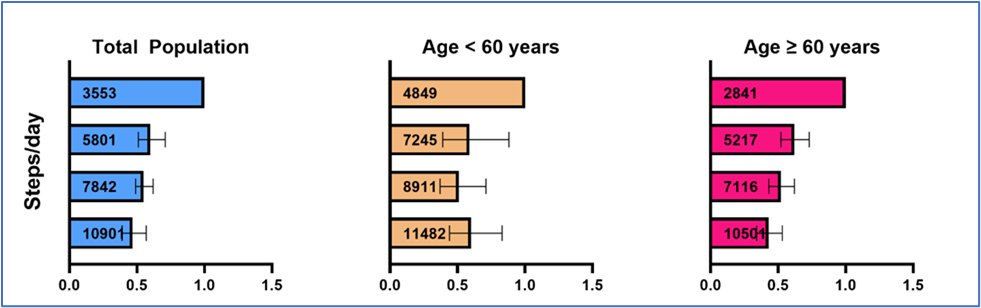

Compelling evidence from a meta-analysis of 15 prospective cohort studies from four continents (Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America) and including over 47,000 adults aged 18 years and older supports age-specific step count thresholds for all-cause mortality risk (Paluch et al., 2022).

Figure 4

Risk ratios for all-cause mortality by step count quartiles. Adapted from Paluch et al, 2022

As seen in Figure 4, the risk of mortality decreases with increasing step counts, but the association is different in younger than older adults. The hazard ratio for all-cause mortality plateaus (e.g., no further decrease in mortality/benefit) at approximately 6000-8000 steps per day in adults aged 60 years and older, whereas in younger adults the plateau was approximately 8000-10,000 steps per day. These data also suggest that increasing steps per day from about 3500 to 5800 is associated with the greatest reduction in mortality risk.

What is “aerobic exercise”?

In the U.S. physical activity guidelines, aerobic exercise refers to continuous movement that causes increases in heart and breathing rates. Aerobic exercise is also often called endurance, cardiovascular endurance, cardiopulmonary endurance exercise, or simply “cardio”. Physiologically, aerobic exercise refers to reliance on oxidative metabolic pathways to produce energy in the form of ATP (Brooks, 1996). Moderate-intensity exercise can be sustained for two minutes or more because the demand for energy production can be met through matched oxygen uptake. Higher-intensity (“vigorous”) aerobic exercise pushes the higher limits of heart rate and respiration. During aerobic exercise, energy for continued effort is produced through multiple pathways and substrates including glycogen, lipids, and amino acids that are stored in muscle, liver, adipose tissue, and/or blood (Brooks, 1996). Numerous mitochondrial adaptations, including size, number, and function, occur at the sub-cellular level (Memme et al., 2021). Because moderate- to high-intensity aerobic exercise is sustainable for longer periods of time, more total kilocalories can be expended per session compared to very high-intensity exercise. Muscle strengthening exercises, unless of very high intensity, also use some aerobic energy production.

The nurse practitioner can advise patients doing very little physical activity to increase steps gradually by walking and encourage patients who are walkers to keep up their beneficial habit. The number of steps a person walks in one mile varies by stride length, but 2000 steps is a reasonable estimate. |

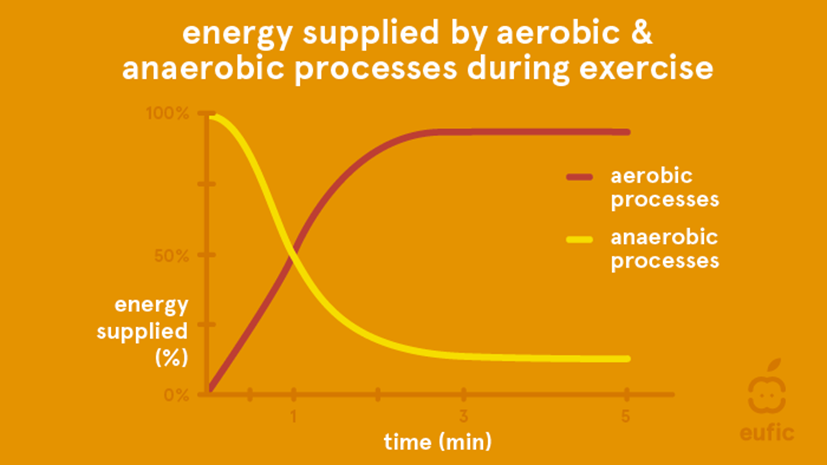

When exercise intensity is very high, such as in a speed event like the 100-meter dash, energy is non-oxidative (anaerobic) and supplied by muscle glycogen and plasma glucose. This is a limited energy supply, sustaining the high effort for less than one minute. Very high single effort (“explosive power”) exercise, such as throwing a shot put or lifting a very heavy weight in the gym, requires an immediate energy source provided by ATP and creatine phosphate stored in the activated muscles, lasting only a few seconds (Brooks, 1996). During an aerobic exercise session that lasts more than a few minutes, the predominant energetic pathway shifts from anaerobic to aerobic metabolism (Figure 5; European Food Information Council, (EUFIC) www.eufic.org), and both systems adapt to targeted exercise training. Some training formats, such as CrossFit (CrossFit, LLC, Scotts Valley, CA, USA), include exercises stimulating aerobic and anaerobic energy pathways.

Figure 5

Aerobic and anaerobic energy systems during exercise. (European Food Information Council)

What is HIiT?

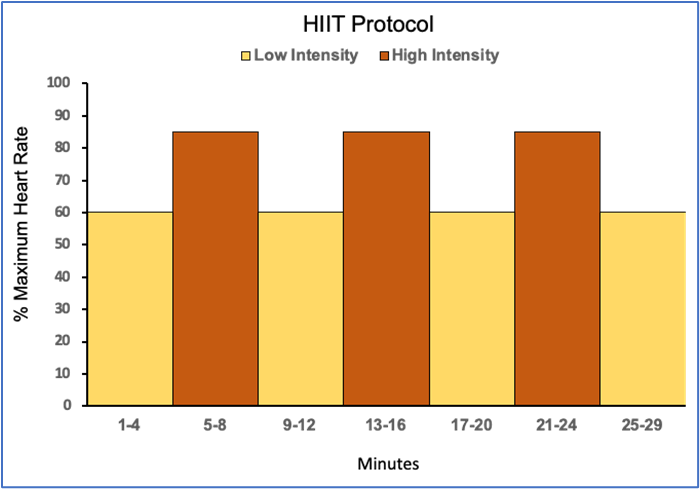

Figure 6. Example of a HIIT protocol for treadmill walking/jogging

HIIT is high-intensity interval training. Although HIIT is used to describe many types of exercise workouts in the fitness industry, it is specific to short intervals of high- to very-high intensity exercise such as running or cycling alternating with lower intensity recovery intervals. The adaptations to HIIT are often compared to continuous moderate-intensity exercise. From an exercise behavior perspective, one advantage of HIIT is that a given caloric expenditure goal can be reached in a shorter session than continuous moderate-intensity exercise. Some people find HIIT less boring than continuous exercise. Figure 6 depicts a HIIT protocol for treadmill walking or jogging that was developed for older sedentary adults. Lower intensity intervals (60% of maximum heart rate) were alternated with higher intensity intervals (85% of maximum heart rate); each interval was four minutes in duration. The number of intervals progressed over several weeks as did the heart rate target for the high-intensity intervals. A 5-minute lower intensity warm-up and cool-down would bookend the series of intervals.

There are many ways to modify a HIIT protocol, including the duration and intervals intensity of the intervals. The common factor in HIIT is that periods of near-maximal intensity exercise are followed by lower intensity recovery intervals. HIIT can be included as one part of an exercise training routine, for example, by alternating with continuous moderate-intensity exercise sessions during the week. Related to HIIT is sprint interval training (SIT), in which supra-maximal exercise for very short periods alternate with lower-intensity recovery periods.

In a meta-analysis comparing responses to HIIT with continuous moderate intensity exercise (Maturana et al., 2021), HIIT was associated with greater improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness (measured by maximal oxygen consumption; d=0.40, 95% CI=0.24-0.57, P< 0.001) and cardiovascular health (measured by flow-mediated dilation; d=0.54, 95% CI=0.05-1.03, P=0.031). The comparative effects of improving cardiorespiratory fitness by HIIT increased with age and were greater in adults with lower pre-training fitness (i.e., more deconditioned). The greater improvements in flow-mediated dilation with HIIT could be explained by higher endothelial shear stress with subsequent nitric oxide release and vasodilation. Conversely, decreases in HbA1c were significantly greater with continuous moderate intensity exercise than with HIIT (d=-0.27, 95% CI=-0.52- -0.01, P=0.040). Other clinical measures, including changes in body fat, blood pressure, blood lipids, inflammatory markers, and glucose tolerance were not significantly different in response to HIIT or continuous moderate intensity exercise. Subpopulations, sex, age, and variations in training protocols were taken into consideration in the meta-analysis (Maturana et al., 2021).

Exercise prescription: fundamental components

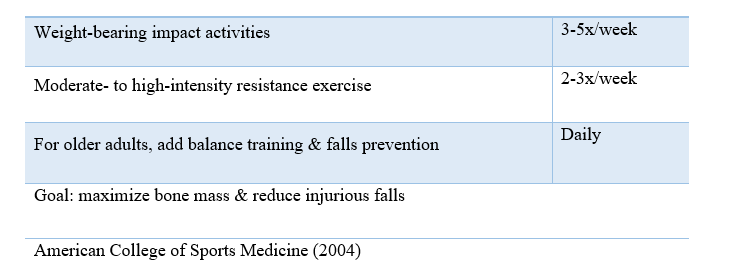

The nurse practitioner who seeks the best available evidence for the benefits of exercise in a patient population will encounter a wide variety of exercise types, intensity, duration, and other descriptors. The FITT Principle (Table 1) can be used to create an exercise prescription and to compare studies. In this acronym, F = frequency, I = intensity, T = time, and T = type (or mode) (American College of Sports Medicine, 2022). The framework can be applied to almost every type of exercise and patient population. An example of FITT for a healthy adult and a person with cancer-related fatigue (Table 1). The U.S. physical activity recommendations for adults have been applied in this example. Exercise intensity is reduced for the person with cancer-related fatigue; daily fluctuations in cancer-related fatigue would also be taken into consideration, and exercise time could be broken into multiple shorter sessions.

Table 1.

Application of the FITT Principle for Exercise Prescription

(American College of Sports Medicine, 2022)

Exercise intensity can be challenging to quantify but multiple options are available. First, a basic physiologic response to aerobic exercise is that heart rate and oxygen consumption increase linearly with increasing work demand. Although the maximal volume of oxygen consumed (VO2 max) at the highest possible exercise intensity is the gold standard for describing cardiorespiratory fitness, it is not easily measured outside of the research setting. Fortunately, heart rate is easier to measure and is used to set goals for exercise intensity. In Table 1, exercise intensity is expressed as a percentage of estimated maximum heart rate and by the rate of perceived exertion (RPE). In persons without known cardiovascular disease, maximum heart rate decreases with age, regardless of sex or whether the individual is highly trained or not (Tanaka et al., 2001). An adult can estimate their maximum heart rate using the well-known equation by Fox et al (Fox et al., 1971):

Maximum heart rate (beats/minute) = 220-age

More accurate equations for estimating maximum heart rate have been developed using rigorous laboratory-based measures and statistical methods, such as the following equation established by Tanaka et al. (Tanaka et al., 2001):

Maximum heart rate (beats/minute) = 208 – 0.7 x age

Table 2. Estimated Maximal Heart Rate (beats/minute) | ||

Age | 220- age | 208-0.7 x ageª |

20 | 200 | 194 |

30 | 190 | 187 |

40 | 180 | 180 |

50 | 170 | 173 |

60 | 160 | 166 |

70 | 150 | 159 |

a (Tanaka et al., 2001) |

As seen in Table 2, the commonly used “220-age” calculation (Fox et al., 1971) overestimates maximum heart rate for younger adults (< 40 years) and underestimates maximum heart rate for older adults (> 40 years), when compared to the equation by Tanaka et al. (Tanaka et al., 2001) The more accurate estimate of maximal heart rate also provides more accurate heart rate

ranges (i.e., “zones”) for submaximal exercise intensities.

Heart rate can be monitored using a fitness tracker, heart rate monitor (e.g., chest strap), or measuring pulse. Some fitness trackers allow the user to select an equation to estimate maximal heart rate and, subsequently, to set limits on “heart rate zones”.

The Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) is a scale that answers the question, “how hard are you working?” There are multiple RPE scales used in clinical and recreational settings. The RPE scores in Table 1 are from the 6-20 Borg Scale (http://www.borgperception.se), which has been used for decades. In RPE scales, numerical values are associated with descriptors, such as, 6= no exertion, 11=light, 15=hard, and 20=maximal exertion in the 6-20 Borg Scale. In a clinically administered exercise stress test, the stages of the test elicit an increasingly greater demand (i.e., greater work) on the cardiorespiratory system. Heart rate will increase with each stage and the participant will experience an increase in RPE. Other scales, such as the Omni Scale (Utter et al., 2004), use a 0-10 scale with descriptors (no exertion to maximal exertion) and RPE scales have been developed for specific clinical populations, such as the modified Borg 0-10 dyspnea scale (Kendrick et al., 2000) for persons with pulmonary disease. The 0-10 range has the advantage of being familiar to patients from other self-report scales commonly used in clinical practice (e.g., pain scales). RPE scales can also be used for resistance exercise (Robertson et al., 2003), although there is an added dimension of muscle-specific work, rather than the whole body. The RPE scale may be more useful and intuitive way to monitor exercise intensity for adults using medications that control heart rate, such as some beta-blockers.

Perhaps the most convenient way to monitor aerobic exercise intensity is the Talk Test. During aerobic exercise that elicits 64-95% of maximal heart rate (i.e., moderate intensity), the exerciser can carry on a conversation, count, or recite a sentence (Reed & Pipe, 2014, 2016). At a higher exercise intensity, cardiorespiratory demand exceeds the capacity to also speak, and the exerciser becomes “breathless” (e.g., more anaerobic), until exercise intensity decreases, or exercise is stopped. Here is a practical example of the Talk Test (Figure 7): two exercise buddies are walking a trail and enjoying conversation. When the trail steepens, cardiorespiratory demand increases and conversation becomes more difficult or may cease until the trail levels, cardiorespiratory demand decreases, and conversation can resume. A person with a chronic condition can use the Talk Test to monitor and adjust exercise intensity as needed, reducing intensity if they are experiencing a higher symptom burden, or increasing intensity when symptoms are less interfering.

Figure7

The talk test: talking is easy during light to moderate-intensity aerobic exercise but difficult during high-intensity exercise

Aerobic exercise for a sedentary adult: starting and improving

In the primary care setting, the nurse practitioner is unlikely to care for a patient who completed a clinic- or laboratory-based exercise stress test in which maximal heart rate was measured. For a deconditioned patient in stable health, a recommended initial exercise intensity is the standing heart rate plus 10-20 beats/minute, which is associated with an RPE in the range of weak/fairly light to somewhat strong/hard (Franklin et al., 2022). The patient should be able to pass the Talk Test while exercising. From this starting place, the patient can progress their conditioning over weeks by increasing exercise time and/or intensity as physiological and behavioral adaptations occur. Increasing aerobic exercise time first, then increasing intensity may reduce the risk of some overuse injuries. Aerobic exercise sessions can be performed on consecutive days. The exerciser can monitor their heart rate and/or RPE as they improve their conditioning.

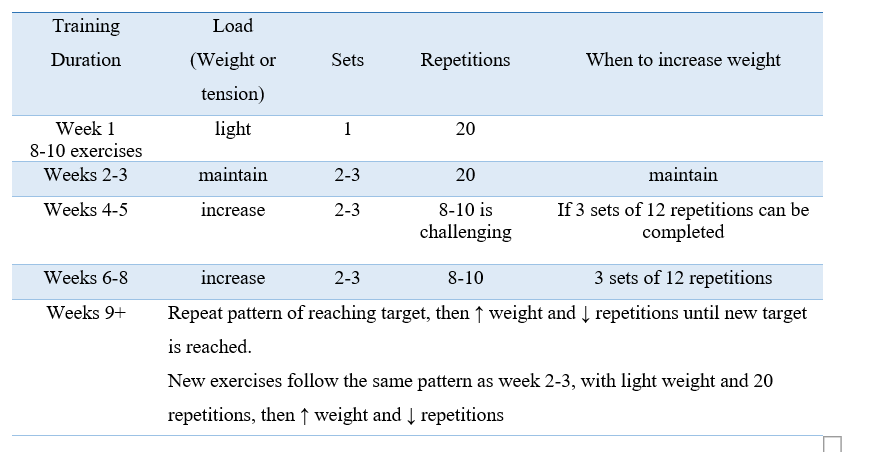

Resistance exercise for a sedentary adult: starting and improving

With regards to resistance exercise, progressive overload is applied to achieve increases in muscle strength (American College of Sports Medicine, 2022). Table 3 provides an overview of progressive overload for a novice, deconditioned person using machine or free weights, or resistance bands.

Table 3 Example of resistance exercise training progression

In this training plan, the exerciser selects 8-10 exercises and choose weights (or band tension) that can be lifted correctly up to 20 times in one set (light intensity). Over two to three weeks, the number of sets (of 20 repetitions) are increased, with about one minute of rest between each set, or in a circuit pattern (completing one set of multiple exercises exercise without rest, and then repeating the sequence). Once this starting weight (or tension) can be lifted 20 times for 2 or 3 sets without causing pain or discomfort, the weight can be increased. At this point, the exerciser has improved their conditioning and learned how to correctly complete the exercises, so the progression plan changes. Using a new greater weight (or tension) the repetitions are reduced to 8 and, as the individual becomes stronger, progresses to 12 per set (moderate intensity). When 3 sets of 12 repetitions can be completed, the pattern is repeated by increasing weight (or tension) and decreasing repetitions.

New exercises can be introduced to the training plan by using a weight (or tension) that allows completion of 20 repetitions, then continue to adjust as described above. An effective warm-up for resistance exercise is 5-10 minutes of range of motion exercises that activate the major muscle groups. Some examples of range of motion exercises are the cat-and-cow movement from yoga, shoulder, wrist, and ankle circles, and alternating side bends. Another warm-up technique is to complete one set of exercises with a lighter weight (or tension) before starting the more moderate intensity weight for two or three sets. Static stretching after the resistance exercise session aids in recovery. Include a combination of upper and lower body exercises in the resistance training plan and give the muscles about 24 hours of rest to allow full recovery before the next exercise session. Resistance exercise has limitless variations, but all have in common the basic principle of progressive overload.

Resistance equipment

Resistance equipment

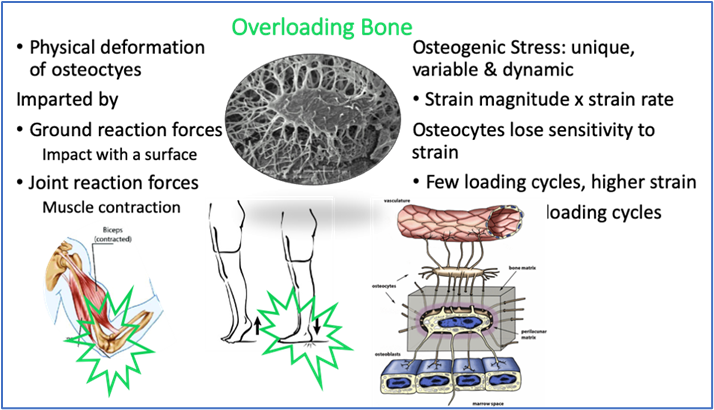

Bone-loading exercise

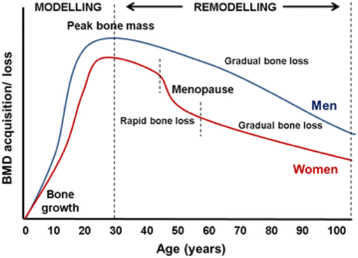

Bone-loading exercise is recommended to all adults to prevent the loss of bone with aging (Kohrt et al., 2004). Peak bone mass occurs in early adulthood in women and men and declines thereafter (Figure 8). In women, the decline in bone mass accelerates in association with the menopause (Kruger & Nell, 2017) Physical inactivity is detrimental to bone, as seen in bed rest studies and observations in astronauts. Low bone mineral density is associated with increased fracture risk in women and men.

When discussing physical activity with sedentary adults, whether they are healthy or have chronic conditions, choose a conservative starting place to avoid overuse injury and discouragement. |

START LOW AND GO SLOW |

Figure 8.

Bone mineral density (BMD) across the lifespan.

Kruger & Neil, 2017. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/ The-general-pattern-of-bone-development-and-loss-over-time-During-years-0-20-bone_fig2_318717217

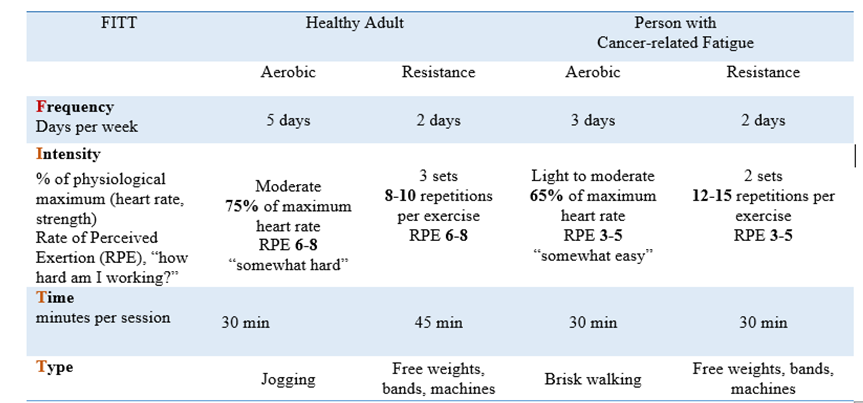

Exercise, by imposing mechanical stress, imparts strain in bone that can trigger cellular signaling for bone remodeling (Figure 9). Embedded in the mineral matrix of bone, the osteocyte functions as a mechanoreceptor, translating deformation from mechanical stress through a signaling network that modulates the actions of osteoblasts and osteoclasts to build and remove bone, respectively (Dallas et al., 2013). For exercise to effectively stimulate bone formation and improve bone strength, it must impart strain that is novel in terms of direction, magnitude, and rate compared to usual forces (Turner & Robling, 2005)

Figure 9

Forces during exercise stimulate osteocytes, leading to bone formation.

from Dallas et al, 2013 and NASA.gov/mission-pages/station/research/news/osteocytes

The types of exercise that seem to effectively stimulate bone formation in adults are weight-bearing impact exercises that impart ground-reaction forces such as jumping, tennis, and running, and resistance exercises (Table 4). During resistance training, the muscular contractions confer stimulus to bone via tendinous attachments and, possibly by muscle-to-bone molecular cross-talk (Bonewald, 2019). Aquatic exercise (Schinzel et al., 2023), yoga, and Pilates (Fernandez-Rodriguez et al., 2021) have not been found to increase bone mineral density but may complement, and/or improve self-efficacy for, targeted bone-loading exercise and impart other health benefits. The LIFTMOR (Watson et al., 2018, 2019) and LIFTMOR-M (Harding et al., 2020; Harding et al., 2017) trials support that supervised high-intensity, progressive resistance and impact exercise improve bone mineral density in middle-aged and older women and men with low bone mass. Additional information and resources for exercise and bone health can be found at the Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation website, https://www.bonehealthandosteoporosis.org.

Table 4. Exercise to Help Preserve Bone Health in Adults