Providing Patient Care

Providing Patient Care

When assessing an individual who is feeling ill but has not yet been diagnosed with an infection, general symptoms associated with the prodromal period of disease may be present due to the activation of the immune system. These symptoms include a feeling of malaise (not feeling well), headache, fever, and lack of appetite. As an infection moves into the acute phase of disease, more specific symptoms and signs related to the specific type of infection will occur.

A fever is a common sign of inflammation and infection. A temperature of 38 degrees Celsius (100.4 degrees F) is generally considered a low-grade fever, and a temperature of 101°F (38.3°C) or higher is considered a fever. Fever is part of the nonspecific innate immune response and can be beneficial in destroying pathogens. However, extremely elevated temperatures can cause cell and organ damage, and prolonged fever can cause dehydration.

Infection raises the metabolic rate, causing an increased heart rate. The respiratory rate may also increase as the body rids itself of carbon dioxide created during increased metabolism. However, be aware that an elevated heart rate above 90 and a respiratory rate above 20 are also criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) in patients with an existing infection.

As an infection develops, the lymph nodes that drain that area often become enlarged and tender. The swelling indicates that the lymphocytes and macrophages in the lymph node are fighting the infection. If a skin infection is developing, general signs of inflammation, such as redness, warmth, swelling, and tenderness, will occur at the site. As white blood cells migrate to the site, purulent drainage may occur.

Some viruses, bacteria, and toxins cause gastrointestinal inflammation, resulting in loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings to Report to Health Care Provider |

Vital Signs | Within normal range | New temperature over 100.4 F or 38 C. |

Neurological | Within baseline level of consciousness | New confusion and/or worsening level of consciousness. |

Wound or Incision | Progressive healing of a wound with no signs of infection | New redness, warmth, tenderness, or purulent drainage from a wound. |

Respiratory | No cough or production of sputum | New cough and/or productive cough of purulent sputum. Adventitious breath sounds (crackles, rhonchi, wheezing). New dyspnea. |

Genitourinary | Urine clear, light yellow without odor | Malodorous, cloudy, bloody urine, with increased frequency, urgency, or pain with urination. |

Gastrointestinal | Good appetite and food intake; feces formed and brown | Loss of appetite. Nausea and vomiting. Diarrhea; discolored or unusually malodorous feces. |

Infants do not have well-developed immune systems, placing this group at higher risk of infection. Breastfeeding helps protect infants from some infectious diseases by providing passive immunity until their immune system matures. New mothers should be encouraged to breastfeed their newborns.

On the other end of the continuum, the immune system gradually decreases in effectiveness with age, making older adults also more vulnerable to infection. Early detection of infection can be challenging in older adults because they may not have a fever or increased white blood cell count (WBC), but instead develop subtle changes like new mental status changes. The most common infections in older adults are urinary tract infections (UTI), bacterial pneumonia, influenza, and skin infections.

Several types of diagnostic tests may be ordered by a health care provider when a patient is suspected of having an infection, such as complete blood count with differential, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR), C-Reactive Protein (CRP), serum lactate levels, and blood cultures (if sepsis is suspected). Other cultures may be obtained based on the site of the suspected infection.

When an infection is suspected, a complete blood count with differential is usually obtained.

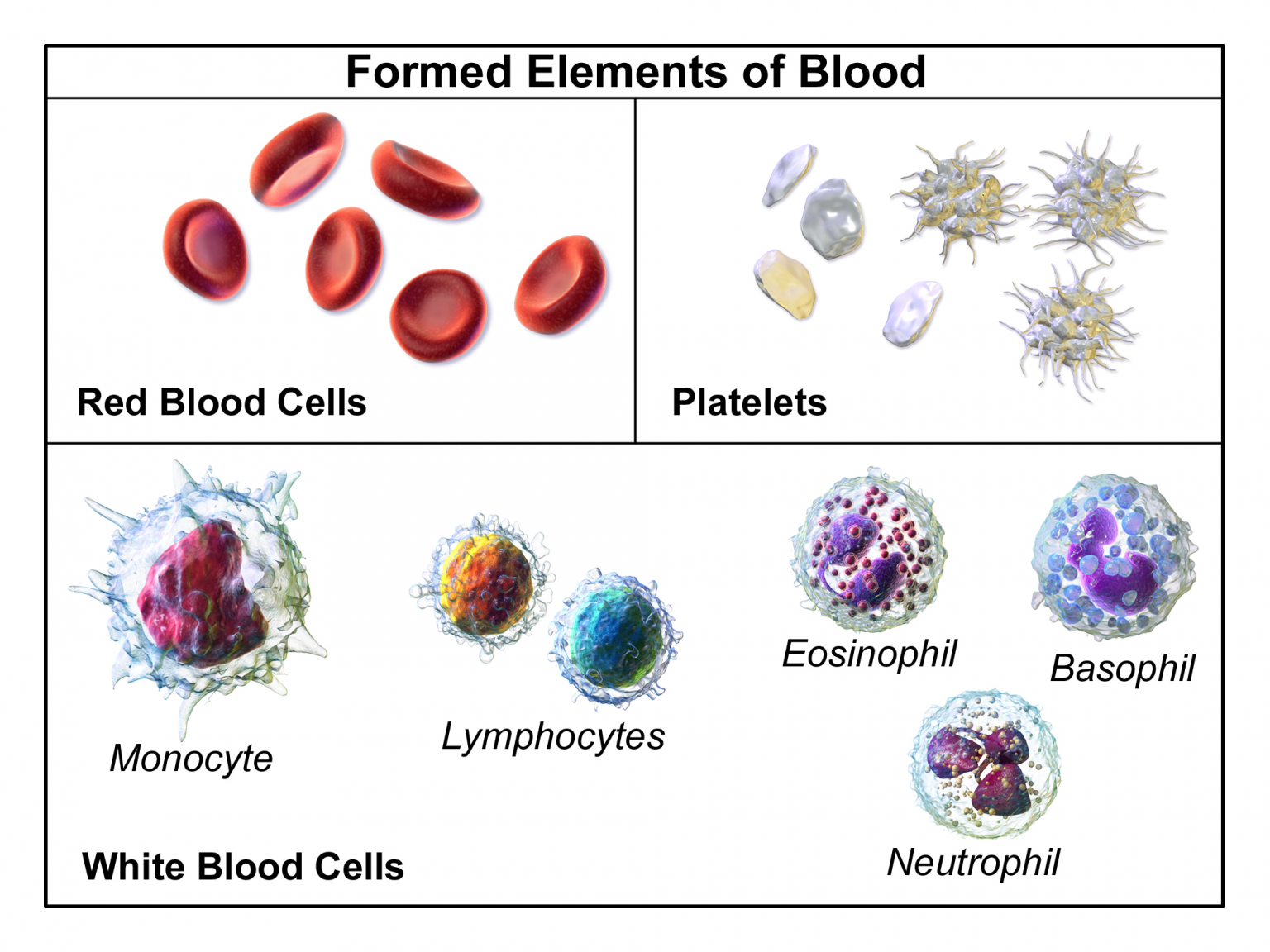

A complete blood count (CBC) includes the red blood cell count (RBC), white blood cell count (WBC), platelets, hemoglobin, and hematocrit values. A differential provides additional information, including the relative percentages of each type of white blood cell. See below for a picture of a complete blood count with differential.

Components of a Complete Blood Count with Differential

When there is an infection or an inflammatory process somewhere in the body, the bone marrow produces more WBCs (also called leukocytes), releasing them into the blood where they move to the site of infection or inflammation. An increase in white blood cells is known as leukocytosis and is a sign of the inflammatory response. The normal range of WBC varies slightly from lab to lab but is generally 4,500-11,000 for adults, reported as 4.5-11.0 x 109 per liter (L).[5]

There are five types of white blood cells, each with different functions. The differential blood count gives the relative percentage of each type of white blood cell and also reveals abnormal white blood cells. The five types of white blood cells are as follows:

- Neutrophils

- Eosinophils

- Basophils

- Lymphocytes

- Monocytes

Neutrophils make up the largest number of circulating WBCs. They move into an area of damaged or infected tissue where they engulf and destroy bacteria or sometimes fungi. An elevated neutrophil count is called neutrophilia, and decreased neutrophil count is called neutropenia.

Eosinophils respond to infections caused by parasites, play a role in allergic reactions (hypersensitivities), and control the extent of immune responses and inflammation. Elevated levels of eosinophils are referred to as eosinophilia. Basophils make up the fewest number of circulating WBCs and are thought to be involved in allergic reactions.

Lymphocytes include three types of cells, although the differential count does not distinguish among them:

- B lymphocytes (B cells) produce antibodies that target and destroy bacteria, viruses, and other “non-self” foreign antigens.

- T lymphocytes (T cells) mature in the thymus and consist of a few different types. Some T cells help the body distinguish between “self” and “non-self” antigens; some initiate and control the extent of an immune response, boosting it as needed and then slowing it as the condition resolves; and other types of T cells directly attack and neutralize virus-infected or cancerous cells.

- Natural killer cells (NK cells) directly attack and kill abnormal cells such as cancer cells or those infected with a virus.

Monocytes, similar to neutrophils, move to an area of infection and engulf and destroy bacteria. They are associated with chronic rather than acute infections. They are also involved in tissue repair and other functions involving the immune system.

Care must be taken when interpreting the results of a differential. A health care provider will consider an individual’s signs and symptoms and medical history, as well as the degree to which each type of cell is increased or decreased. A number of factors can cause a transient rise or drop in the number of any type of cell. For example, bacterial infections usually produce an increase in neutrophils, but a severe infection, like sepsis, can use up the available neutrophils, causing a low number to be found in the blood. Eosinophils are often elevated in parasitic and allergic responses. Acute viral infections often cause an increased level of lymphocytes (referred to as lymphocytosis).

An erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is a test that indirectly measures inflammation. This test measures how quickly erythrocytes or red blood cells (RBCs) settle at the bottom of a test tube that contains a blood sample. When a sample of blood is placed in a tube, the red blood cells normally settle out relatively slowly, leaving a small amount of clear plasma. The red cells settle at a faster rate when there is an increased level of proteins, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), that increases in the blood in response to inflammation. The ESR test is not diagnostic; it is a nonspecific test indicating the presence or absence of an inflammatory condition.

C-Reactive Protein (CRP) levels in the blood increase when there is a condition causing inflammation somewhere in the body. CRP is a nonspecific indicator of inflammation and one of the most sensitive acute phase reactants, meaning it is released into the blood within a few hours after the start of an infection or other cause of inflammation. The level of CRP can jump as much as a thousand-fold in response to a severe bacterial infection, and its rise in the blood can precede symptoms of fever or pain.

Serum lactate levels are measured when sepsis is suspected in a patient with an existing infection. Sepsis can quickly lead to septic shock and death due to multi-organ failure so early recognition is crucial. Lactate is one of the substances produced by cells as the body turns food into energy (i.e., cellular metabolism), with the highest level of production occurring in the muscles. Normally, the level of lactate in blood is low. Lactate is produced in excess by muscle cells and other tissues when there is insufficient oxygen at the cellular level.

Lactic acid can accumulate in the body and blood when it is produced faster than the liver can break it down, which can lead to lactic acidosis. Excess lactate may be produced due to several medical conditions that cause decreased transport of oxygen to the tissues, such as sepsis, hypovolemic shock, heart attack, heart failure, or respiratory distress.

Blood cultures are ordered when sepsis is suspected. In many facilities, lab personnel draw the blood samples for blood cultures to avoid contamination of the sample. With some infections, pathogens are only found in the blood intermittently, so a series of three or more blood cultures, as well as blood draws from different veins, may be performed to increase the chance of finding the infection.

Blood cultures are incubated for several days before being reported as negative. Some types of bacteria and fungi grow more slowly than others and/or may take longer to detect if initially present in low numbers.

A positive result indicates bacteria have been found in the blood (bacteremia). Other types of pathogens, such as a fungus or a virus, may also be found in a blood culture. When a blood culture is positive, the specific microbe causing the infection is identified and susceptibility testing is performed to inform the health care provider which antibiotics or other medications are most likely to be effective for treatment.

It is important for nurses to remember that when new orders for both antibiotics and a blood culture are received, antibiotics should not be administered until after the blood culture is drawn. Administering antibiotics before the blood culture is drawn will impact the results and adversely affect the treatment plan.

Several types of swabs and cultures may be ordered based on the site of a suspected infection, such as a nasal swab, nasopharyngeal swab, sputum culture, urine culture, and wound culture. If a lower respiratory tract infection is suspected, a chest X-ray may be ordered.

When antibiotics are prescribed to treat an infection, some types of antibiotics require blood tests to ensure the dosage of the medication reaches and stays within therapeutic ranges in the blood. These tests are often referred to as peak and/or trough levels. The nurse must be aware of these orders because they impact the timing of administration of antibiotics.