Meaning and Memory Through the Visual Art of the Shoah

Meaning and Memory Through the Visual Art of the Shoah

The category of "Holocaust Art", or the Art of the Shoah, is not as finite and fixed as one might think. The exploration of such a complex and horrific event in history calls for many methods of inquiry, and the visual arts is one that has repeatedly been called in to question. How does the recreation of these events in the visual arts serve the memory of the Shoah? Is it possible to represent such atrocities in an abstract artistic medium? Or should the recollection of these events take the form of something along the lines of a documentary? The artists I will explore here have done all of this and then some, as this category of Visual Art attempts to both reconcile the events of the Shoah, pay tribute to those lost, create a visual record of the violence/destruction, and allows the artists to make sense of themselves after experiencing this violence firsthand.

"With the passage of time, memories of any major historical event diminish, and strategies of recall evolve. Within survivor communities private memories are subsumed into collective memory which in turn becomes the group's epistemological ground and the imagination's battlefield...To study the codes of memory - private and public - embedded in poetic language is to reveal an ongoing process by which the past is being continually renegotiated into the present" (Ezrahi 1989).

Considering the visual arts as a form of "poetic language" as a visible set of symbols and metaphors, is where I begin my inquiry into the role of this medium and how it represents the Shoah. The three artists I have chosen, some more than others, all rely on the visual collection of symbols and the meaning behind them to represent the horrors they have witnessed firsthand. These events have shaped them as people, and therefore shape how they represent the way they have been affected by them. Each artist started their lives as someone who studied the arts, but became shifted in their expression as they went through the imprisonment and persecution under the Nazi's. A large part of the Nazi's program was destruction of not only people, but of culture as well, leaving a vacuum to be filled by creators of culture. Their "private memories" become "collective memories" through the creation of their art. They both make sense of the "private memories", and share them as a "collective" record of what had happened to them. Through this synthesis of the memories they have, and "renegotiating the past with the present", they create what can be called a visual language of symbols and meaning, referred to here as "poetic language". This "language" is the core of their art, where they continually make sense of the events that have shaped them and the world around them.

Alone

Alone

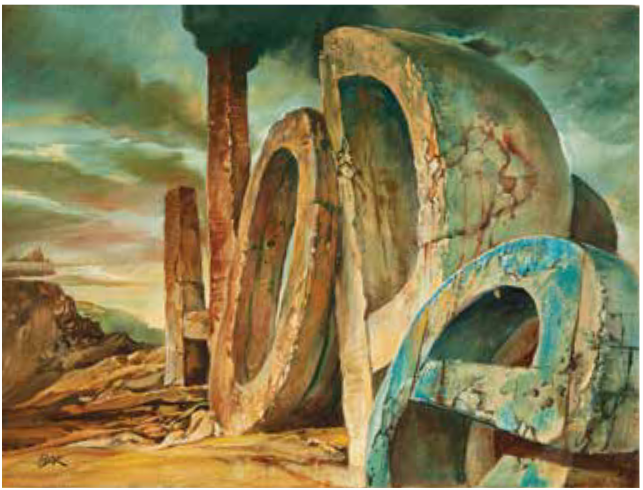

"I felt that I had a story to tell, and I wanted to touch other people. And I wanted to tell them something, and I could not say it directly, because people are kind of reluctantly accepting graphic images. I wanted to tell them something, what did I want to tell them? I want to tell them that there once was a world and the world was destroyed, and I wanted to speak also about the survivors, and I wanted to say that the survivors are people who try to rebuild something that is similar to the reality that existed once, but cannot be totally reconstructed" (Bak 2017).

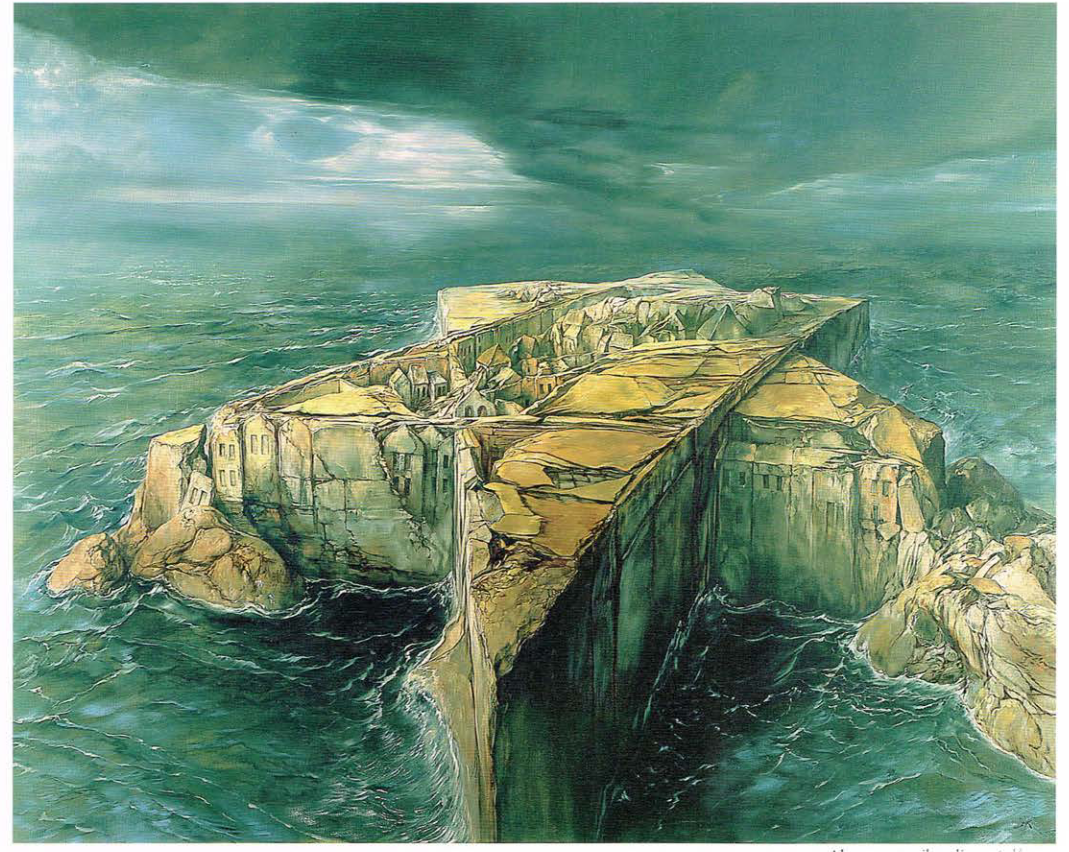

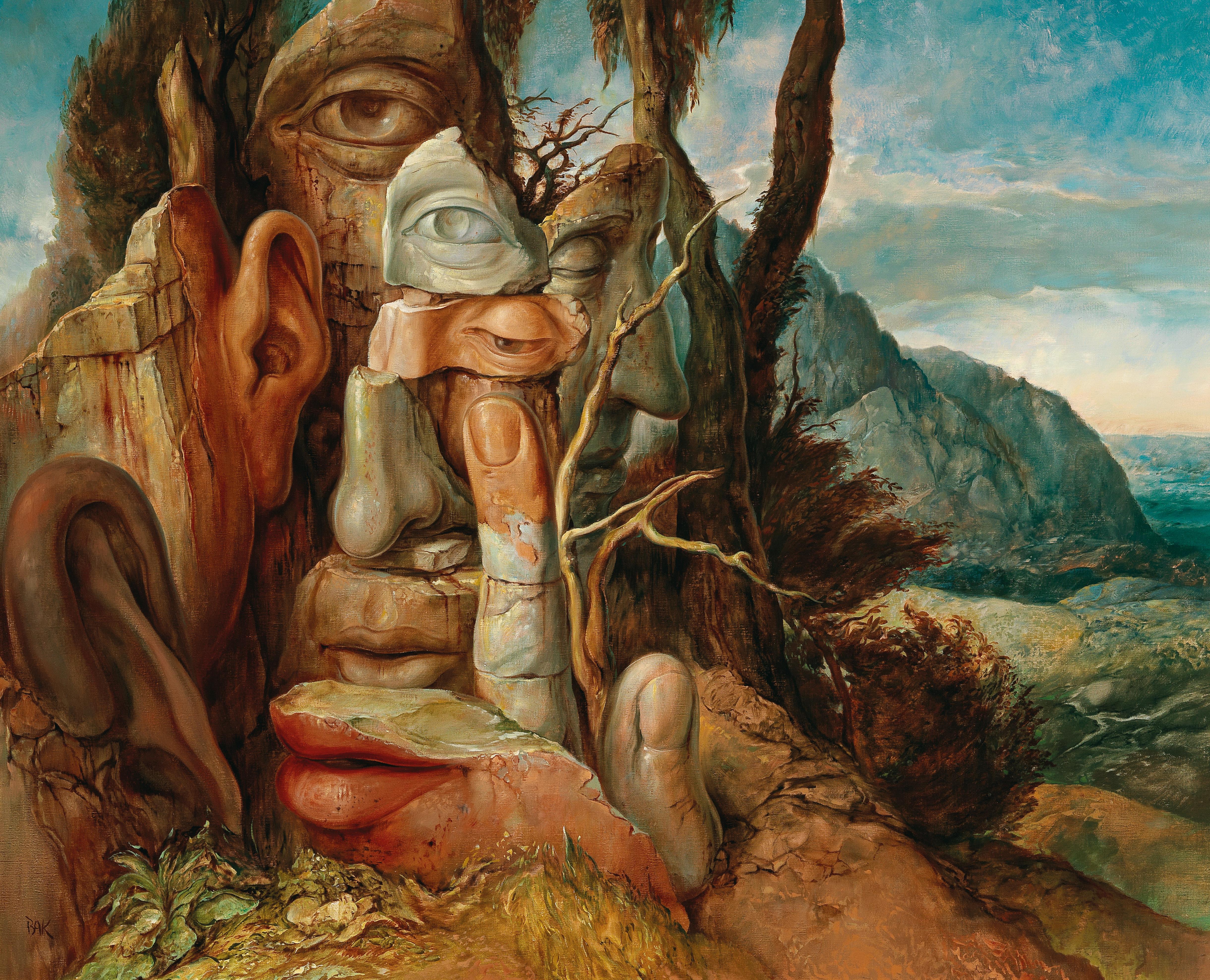

Landscape with Five Senses

Landscape with Five Senses

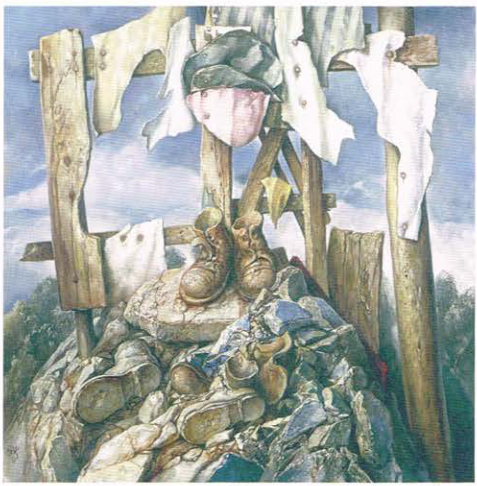

Bypassing

BypassingSamuel Bak's visual language is composed of many different symbols, but a distinct style of the contrast between a "destroyed world" and "rebuilding" a world (Bak 2017). The composition being based off of the idea of "reconstruction" is the central theme in Bak's art that is seen in other artists work as well. Rebuilding after such a horrific event such as the Shoah is a common theme among Shoah Art, with "total reconstruction" not being possible. Therefore we see a very fragmented rebuilding of a world in Samuel Bak's work. It calls into question whether it is being rebuilt, or torn down. The position of the work is between destruction and reconstruction, with neither being clearly represented or "possible", as Bak says.

Another common theme among the art of the Shoah is that of documentation. With so much destruction of people, culture, records, and photographs, there is a vacuum left that art has the potential to fill. It is this vacuum in which David Olère's work resides. As one of the "sonderkommandos", or a person in charge of cleaning out the gas chambers of the dead bodies, David witnessed some of the most graphic and incomprehensible moments of the Shoah. With the absence of photographic documentation of these horrors, he took it upon himself to document these moments and actions through his art.

GassingIn literally depicting these moments as he witnessed them firsthand, we now have a visual record that attempts to convey some of the most horrific moments of the Shoah. In this piece, Gassing, we see a container labeled "Zyklon B", which was the gas created to murder those who entered these chambers. There is a combination of emotion in the people depicted, and factual representation of the events that took place. Shoah art attempts to do both, convey the emotional trauma of the people who were killed, and provide a record where one was not kept in the first place. The act of documentation through art is another common theme we see in Shoah art.

GassingIn literally depicting these moments as he witnessed them firsthand, we now have a visual record that attempts to convey some of the most horrific moments of the Shoah. In this piece, Gassing, we see a container labeled "Zyklon B", which was the gas created to murder those who entered these chambers. There is a combination of emotion in the people depicted, and factual representation of the events that took place. Shoah art attempts to do both, convey the emotional trauma of the people who were killed, and provide a record where one was not kept in the first place. The act of documentation through art is another common theme we see in Shoah art.  Their Last Steps

Their Last StepsThe final moments of those who entered the gas chambers have been thought to never be seen or captured by photographic record, so it is through David's art that we have at the very least, an attempted recreation of these moments, and at the most, documentation of these moments.

The Oven Room

The Oven RoomThe importance of David Olère's work is providing us a record of buildings, labor, and moments from the Shoah that otherwise would never be seen. In this piece, The Oven Room, we see the actual construction of these rooms and the horrors they were utilized for. The trough along the right was to facilitate the dragging of bodies from the gas chambers. The black and white composition of these convey a bleak depiction of the labor of those chosen to do this work, which is undoubtedly an accurate representation of these people's jobs.

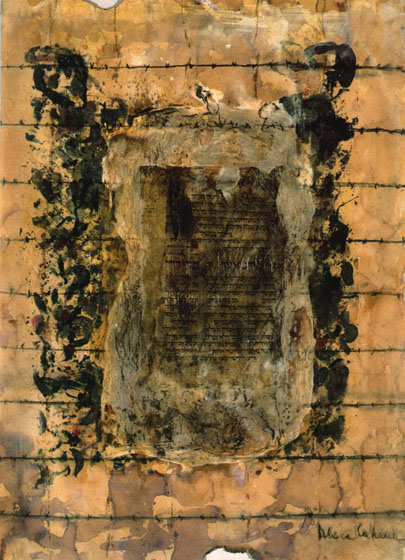

Lamentations is one of the most poignant pieces I have come across from Cahana's body of work. Slightly less abstract than her other work, we get a a more pressing sense of the mission that Cahana has given herself. As art historian Barbara Rose wrote in regards to Cahana and her work, she is "Determined to overcome the contradiction between aesthetics and mass murder, two irreconcilable opposites representing the highest and lowest levels of human consciousness" (Rose 1986). In attempting to translate the experiences she went through in Auschwitz, this piece shows us a page from the Torah, the Jewish holy book, behind a wall of barbed wire. The immediate symbology of containing a page from the holy book of the Jewish faith behind a barbed wire fence is seen, and the viewer feels more aligned with not only the humanistic experience of being imprisoned, but the cultural effect of the Shoah as well. The destruction sought by the Nazi regime was not just based in imprisoning and killing the humans that they persecuted, but destroying the culture altogether. The book burnings of the Shoah were an early sign of what was to come, and the destruction of the Jewish culture was second only to the destruction of its people. Cahana's art seeks to represent this here. It also works as a medium to translate her own personal experience of being imprisoned. When viewing this piece, we get a constricted feeling, like if we wanted to reach out and touch the page of the Torah, we couldn't. Reaching the absolute understanding of what it meant to be in Auschwitz is in this same vein. Unless we were there, we cannot truly understand the incomprehensible horror, but the aim of the piece alone is not to translate this. It is to give us a "glimpse of the story" (Cahana), and alongside other pieces from survivors, whether it is firsthand accounts or more abstract representations such as this, we can hopefully achieve a level of understanding and empathy that honors those that went through this experience themselves.

After the End

After the EndThe Shoah is a time of incomprehensible violence, trauma, and pain for individuals who survived, children and family of survivors, and anyone in close proximity to its effects. This level of pain and violence warrants a reflex that it is negative, and the act itself is. But the central question that these artists here have at the very least asked, and at the most attempt to answer, is what does one do with this pain and memory? And the audience is asked the same thing. How does one take the memory translated through an artistic medium and do something with it? What comes of a secondary experience from a piece of art? In asking this question of pain and suffering, Sungju Park-Kang in their paper Pain as Masquerades/Masquerades as Pain remarks "Pain has many faces and works with a complicated picture. It constitutes one of the core features of human affairs. One could reflect on pain and injury, which might lead to a different kind of politics, rather than just dismiss and forget" (Park-Kang 161). When much of the world tends to "dismiss and forget" the pain and suffering of those who experience genocide, the act of these artists of the Shoah is to "reflect on pain", and preserve and process the memory of this "pain", so others who did not experience it firsthand may "lead to a different kind of politics", one which does not lead to war and genocide. The art of the Shoah holds a particular place in the history of the world, giving those who weren't there a chance to glimpse the horror behind the acts, but hold the humanity of those who suffered in their hands.

Man, Women, and Child (Bak)

Man, Women, and Child (Bak)

Not to let the world forget. My art and my writing are my Kaddish for those who did not survive" (Cahana).

Homage to Raoul Wallenberg

Homage to Raoul Wallenberg Alice Lok Cahana self describes her art as her "Kaddish", or a Jewish prayer for the dead. Her art encapsulates the form of Shoah art as a method of tribute for those that have past. Ironically enough, she also takes the viewpoint that "No words are adequate for this task. The art cannot express it" (Cahana). She gives power to the idea that these events are unable to be expressed through words or art, yet she tries anyway as a form of tribute. She speaks of the "silent oath" to "tell a glimpse of the story". Each piece made, whether it adequately retells of the destruction and violence or not, is a piece of the larger puzzle. Shoah art as a category in the whole attempts to piece together this puzzle of retelling the story, with each piece of art lending a part to the legacy of the Shoah.

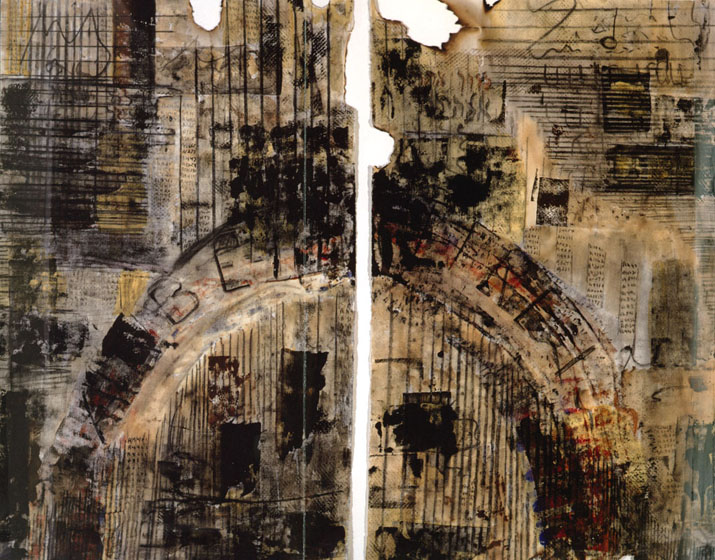

Concert in Auschwitz

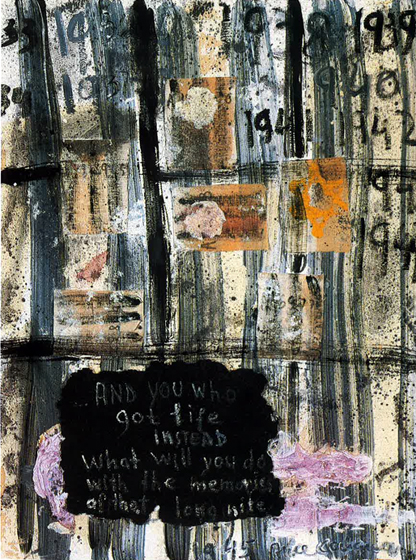

Concert in AuschwitzThese two pieces of Cahana's in particular lend a specific piece to this puzzle. The first one, Homage to Raol Wallenberg, is actually composed of some of the passport books that Roal Wallenberg fabricated to save Jews in Budapest. Her inclusion of the literal passports that were used pays direct homage to the actions of those who attempted to save Jews during the Shoah, and incorporates fragmented pieces of the history of the Shoah. The use of collage techniques is a metaphor for the layers and fragmented pieces of life that were destroyed or saved during this time period. In this same vein of creating wholeness from including fragmented or partially destroyed pieces of history in her work, the second piece Concert in Auschwitz includes sheet music of Jewish songs, a testament to not just the people who died in Auschwitz, but the culture of the people who died.

In this video, Samuel Bak shares his mission through his art, and interlaces it with his family's story under the Nazi regime.

He speaks of people's "reluctance to accept graphic imagery" (Bak), which is why he relies so much on metaphor and symbology. He knows he has a story to tell, but doesn't want to let it get muddled among graphic imagery that will turn people away.

Samuel Bak

Born in 1933 in Vilna, Poland, Samuel Bak came to age during a crucial time in the onset of the events of the Shoah. During the years of 1940-1944, Vilna was under Soviet control, and then transferred to German control. His first exhibition was in the Vilna Ghetto at only nine years old, and his talent was noticed immediately. During this time of occupation, Bak's father and four grandparents perished at the hand of the Nazi's. After the war, Samuel and his mother fled to the displaced person's camp in Landsberg, where he took up painting lessons at the Blocherer School in Munich. Anywhere he moved, Samuel Bak continued his artistic education, culminating in exhibitions in Rome and solo exhibitions in the Jerusalam and Tel Aviv museums in 1963. His art has been shown all over the world in the decades since, and his name has become almost synonymous with "The art of the Holocaust". He now lives in Boston after becoming a citizen in 1993. (Pucker Gallery)

Alice Lok Cahana

Alice Lok Cahana was born in 1929 in Savar, Hungary. Enrolled in a Jewish High School, she first learned to draw here while attending, and shortly after was sent to Auschwitz and Bergen-Belson concentration camps. She was one of the few that survived, and subsequently moved to Sweden from 1952 to 1957. Afterwards, she moved to Houston, Texas where she discovered her artistic expression among the more abstract "colorfields" movement that was taking root there at the time. After this time studying at the University of Houston and Rice University, she made a pivotal decision to return to her home in Savar, where she discovered that "nothing remained of the Jewish community she had known: "The same railroad tracks that took me to Auschwitz took me back. It seemed like nothing had changed there - the town was still mute and silent - no memorial, no remembrance, no one missed us or cared. It was one of the most shocking events I experienced after the Holocaust" (Purdue). After this trip, her art took extended from her abstract roots to the form that we know her for today, creating visual memorials for the dead who perished during the Shoah.

David Olère

David was born in Warsaw, Poland in 1902. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts until he was 16 in Poland. During these years he displayed wood cuts and other art at art houses in Danzig and Berlin. After this he worked as a set designer for the Europäische Film Allianz, and even briefly for Paramount Pictures in Europe. In 1930 he married his wife Juliette Ventura and had their son Alexandre. When war was declared in Europe, he was drafted into the infantry regiment in France, and during 1943 was arrested by French Police during a round up of Jews. After this he was sent to Auschwitz where he worked as a "sonderkommando", and was responsible for emptying the gas chambers after rounds of murders occurred. In addition to these horrors, he also witnessed countless others such as the medical experiments done on the old and sick the rape of women prisoners at the hand of SS soldiers. These events that he witnessed became the basis for the art he created during and after his imprisonment in Auschwitz, creating a visual documentary of events that photography never touched.

The visual language and metaphors used by Samuel Bak are some of the most striking symbols I have come across in the Art of the Shoah. In this famous piece Absence (Bak 1997), we see a method of Bak's art that we see throughout his pieces, the use of negative space to evoke a sense that something is there, but not in the whole sense. The image appropriated here is of a famous picture of a boy surrendering in the Warsaw Ghetto (pictured below).

Utilizing this famous image in his own visual metaphor is Bak's way of bringing factual/photographic testimony of the Shoah to his art, and intertwining it with his own experience as well. The reconstruction of something that was there before using the debris of the city and every day objects is a symbol that Bak uses throughout his work. A viewer gets the sense of the boy through the negative space, and the attempt to make his image from the rubble of the city scape is a metaphor for the attempts to create a life after the Shoah. He is not wholly recreated, as seen with the negative space, but an outline of him remains. The question asked continually through Bak's work is whether this reconstruction is possible after such an event. He is simultaneously attempting to do this for himself through the work, and also causing the viewer to ask the same question. If it was possible, I think Bak would have simply painted a portrait, but the way he is portraying the boy through the negative space of the crumbling city around him evokes questions of the possibility of recreation or reconstruction after the Shoah.

As a direct witness to the one of the most horrifying aspect of the Shoah, the gassing of massive groups of people, David Olère tends to insert himself into his own paintings as a sort of self portrait. Here we see a recreation of a radical act of resistance that Olère participated in. After those imprisoned and chosen for gassing undressed and entered the chamber, he went through the belongings of those who perished to gather the food they had brought with them in order to throw it over the fence to other sections of the camp for others to eat. Along with the violence and death of the Shoah, there was rarely visual documentation of the acts of resistance that Jewish prisoners used to fight for survival. This is the most striking theme in Olère's work, that he was able to document the moments that would otherwise have been long lost and forgotten. In this way, his work directly affects the memory of the events of the Shoah, providing a record of the parts that would otherwise have perished at the hands of the Nazi's. In the foreground of the painting we also see a small doll, giving us a symbol for the range of lives lost in the gassing. This method of genocide affected everyone, no matter what age group or gender they belonged to. Including this in the painting both assists Olère with at the least, processing these memories, and at the most, ridding himself of having to return to it over and over. For the viewer of the art, it is a stark reminder of the far reaches of the violence of the Shoah. In the background of the painting we have another symbol, perhaps on a more spiritually optimistic note. The cart of bodies being walked away towards a building in the background is being illuminated by a beam of light that is cutting through the clouds. This seems to be included in the painting as a reminder to those viewing it that even when death and violence was the core of the Shoah, those that perished should be the centered focus of the events. The light being cast on to the bodies brings our attention to them in the painting, as it should always be brought to outside of the painting. In attempting to understand the Shoah, those that were the victims or survivors should always be centered, and not the narratives of those that enacted the violence.

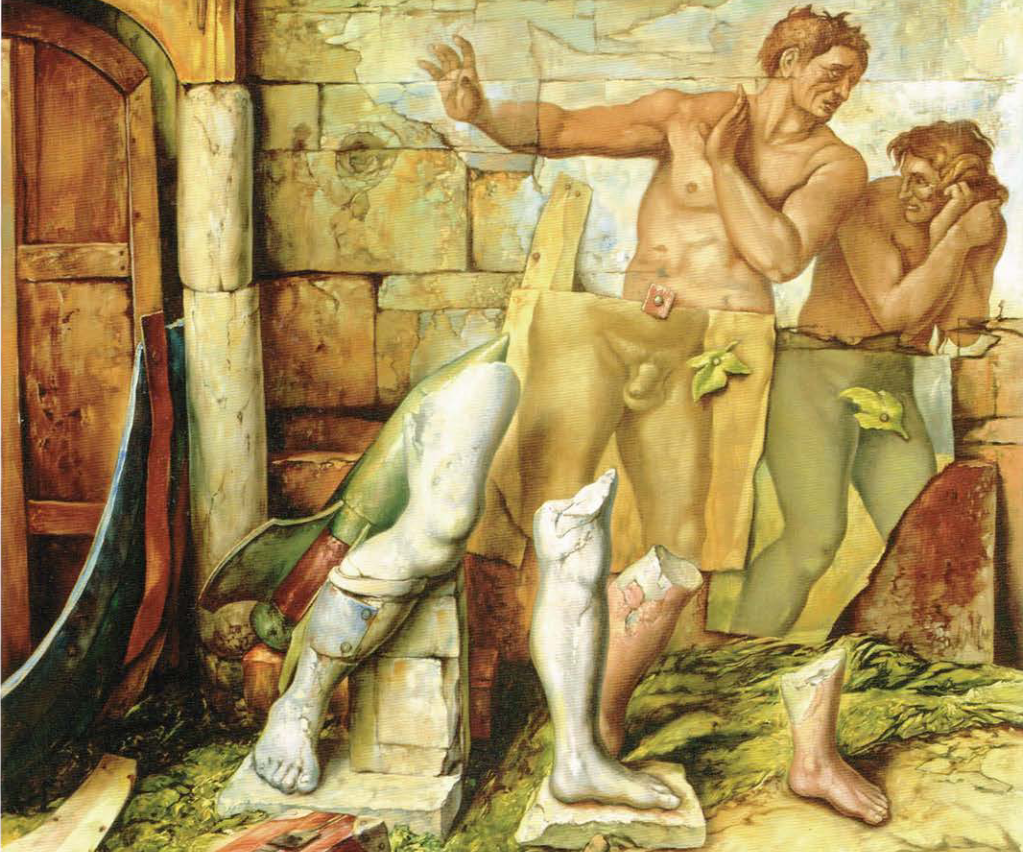

Banishment (Bak - Partial Screenshot)

Banishment (Bak - Partial Screenshot)

Destruction of the Jewish People (Olere 1946)

Destruction of the Jewish People (Olere 1946) And You Who Got Life Instead (Cahana 1978-79)

And You Who Got Life Instead (Cahana 1978-79)