Resistance Through Photography: Preserving the Truth of the Holocaust

Resistance Through Photography: Preserving the Truth of the Holocaust

↠ Research Question: How was photography used a form of resistance during the Holocaust? ↞

re.sist.ance - the refusal to accept or comply with something; the attempt to prevent something by action or argument.

When we think of resistance during the Holocaust images of armed resistance fighters ambushing groups of Nazis with guns blazing often come to mind. However, forms of unarmed resistance during the Holocaust, especially photography, proved to be just as dangerous for the Nazis in the long run. This research project focuses of five different Holocaust photographers who risked their lives to preserve the photographs they took (oftentimes secretly) of the horrific situations around them.

PLEASE BE AWARE – Some of the photographs depicted on this web page are immensely disturbing . While creating this project I questioned whether it would be ethical to use certain photographs, however, I ultimately decided that the best way to honor the victims of the Holocaust was to preserve the truth by showing these images. Every victim of the Holocaust deserves to have their story told without censorship.

"Jureczek and I were ordered to burn the negatives in the furnace and we took out what was left of them. We were doing it under Walter’s supervision. Before we left the camp on January 18, 1945, we secured the negatives in the laboratory, boarding the entrance up so that no one could get in there." (Testimony of Wilhelm Brasse provided by Auschwitz.org).

"At the last moment we were ordered to burn all the negatives and photographs kept in Erkennungsdienst (Identification Department). First, we put wet photo paper into the tile furnace in the laboratory and then loads of photos and negatives. Such an amount of material prevented the smoke from escaping. When we lit the furnace, we thought that only some of them, at the furnace door, would burn and then the fire without oxygen would be put out. (…) Pretending to be in hurry, I deliberately scattered some of them around the rooms of the laboratory. I knew that during the hurried evacuation, nobody would have time to take everything and something would survive." (Testimony of Bronislaw Jureczek provided by Auschwitz.org).

Thanks to the bravery of Brasse and his colleague, around 38,000 photos from Auschwitz were preserved. Many of Wilhelm Brasse's photos were used as evidence to convict the Nazis of their horrible crimes against humanity. These photos can be seen today at the Auschwitz Museum, in numerous books, and in documentaries. Wilhelm Brasse passed away in Poland in 2012.

Wilhelm Brasse before the start of WWII (c. 1938). .

Wilhelm Brasse before the start of WWII (c. 1938). .

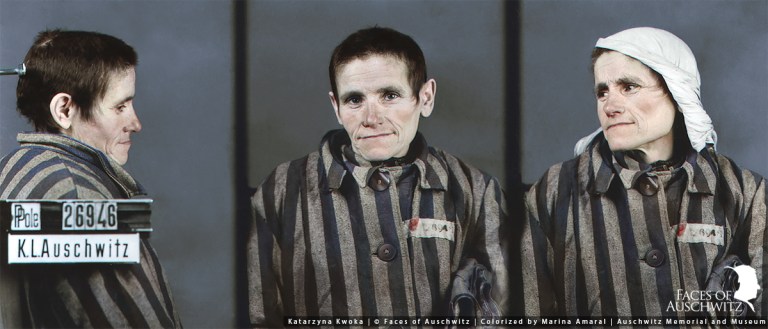

Identity Photograph of Czeslawa Kwoka taken by Wilhelm Brasse (c.1942).

Identity Photograph of Czeslawa Kwoka taken by Wilhelm Brasse (c.1942).

↠ Czeslawa Kwoka ↞

Czeslawa Kwoka was born in Poland on August 15, 1928. She was a Polish Roman Catholic. Czeslawa and her mother, Katarzyna Kwoka (both pictured above), were displaced by the Nazis and subsequently shipped to Auschwitz in December 1942. The memory of Czeslawa Kwoka was burned into Wilhelm Brasse's mind:

“She was so young and so terrified. The girl didn’t understand why she was there and she couldn’t understand what was being said to her. So this woman Kapo (a prisoner overseer) took a stick and beat her about the face. This German woman was just taking out her anger on the girl. Such a beautiful young girl, so innocent. She cried but she could do nothing. Before the photograph was taken, the girl dried her tears and the blood from the cut on her lip. To tell you the truth, I felt as if I was being hit myself but I couldn’t interfere. It would have been fatal for me. You could never say anything.” (Testimony of Wilhelm Brasse provided by Auschwitz.org).

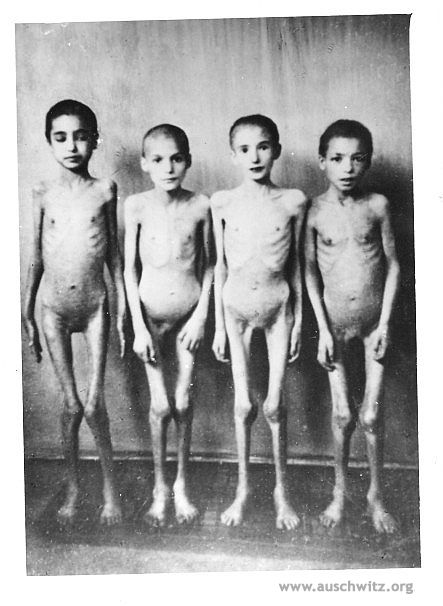

The only known surviving photo of Josef Mengele's medical experiments on prisoners. Photo taken by Wilhem Brasse (c. 1943).

The only known surviving photo of Josef Mengele's medical experiments on prisoners. Photo taken by Wilhem Brasse (c. 1943).↠ Victims of Josef Mengele ↞

According to information found on Auschwitz.org, Mengele's secretary and a female Kapo brought four Jewish girls to Brasse for photographs. They were two sets of twins, about 12-15 years old, so skinny that their uniforms hung off their bodies. Mengele had requested full-length photos of them unclothed. Once the girls understood that they needed to undress they began to cry. Brasse had an idea, grabbing a big display screen used as a backdrop for portraits of the SS, he advised them to undress behind it. After they undressed, the girls came out from behind the screen looking frightened and embarrassed. While looking through the viewfinder of his camera, Brasse realized that the girls had been starved. Their ribs were protruding, and their stomachs and thighs were so sunken that he might have encircled them with his hands. Years later, Brasse still remembered how hard he fought to hold back his tears at that moment. After taking the photographs, Brasse asked Mengele's secretary — herself a Polish prisoner — what Mengele did to the girls. All she knew, she stated, was that he measured and weighed them. Brasse took some of his bread and asked the secretary to sneak it to the girls. She obliged. The fate of these four children remains unknown, although, they most likely perished in Auschwitz.

↠ Picturing Auschwitz ↞

(YouTube. Courtesy, AFP News Agency).

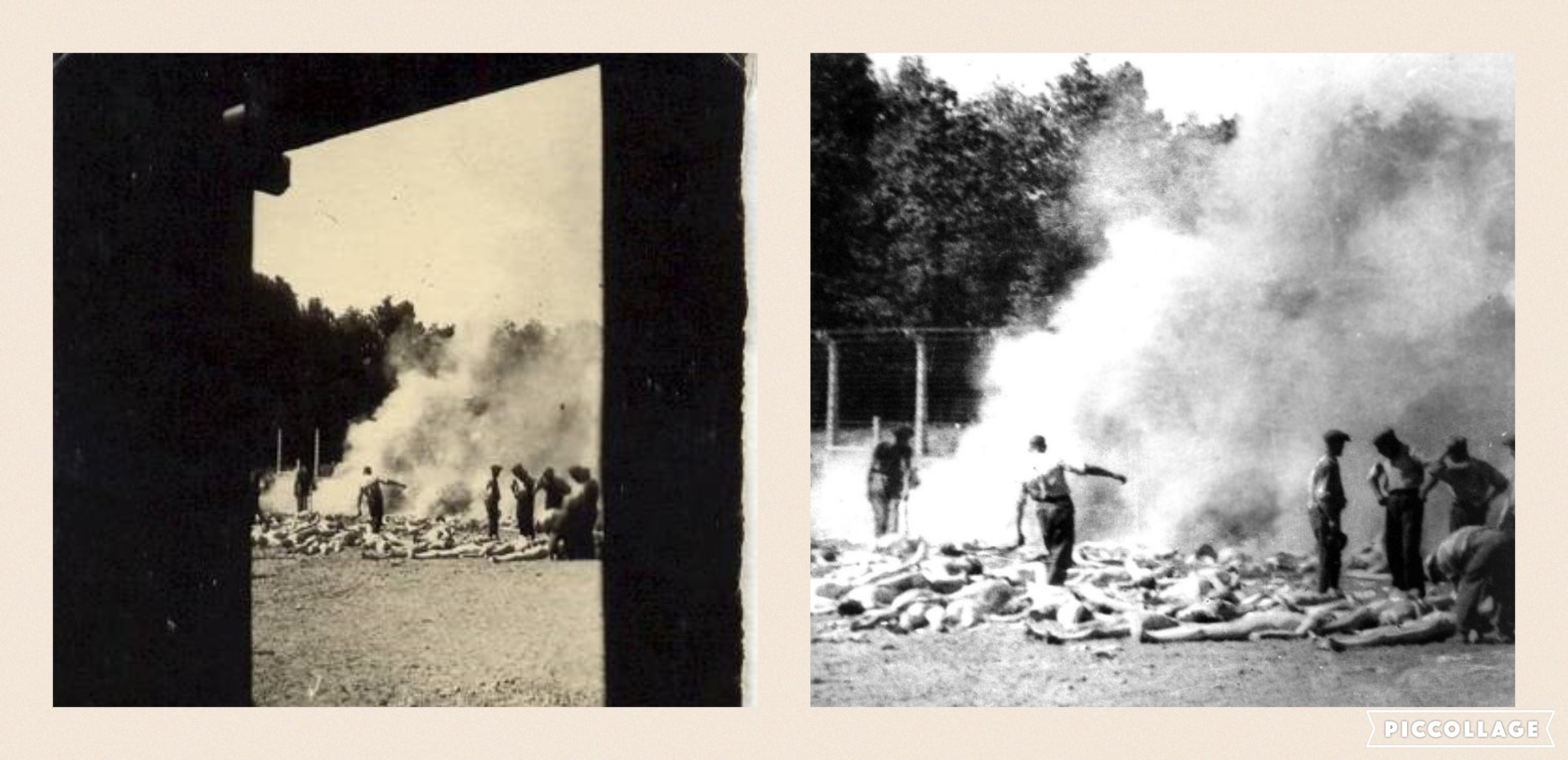

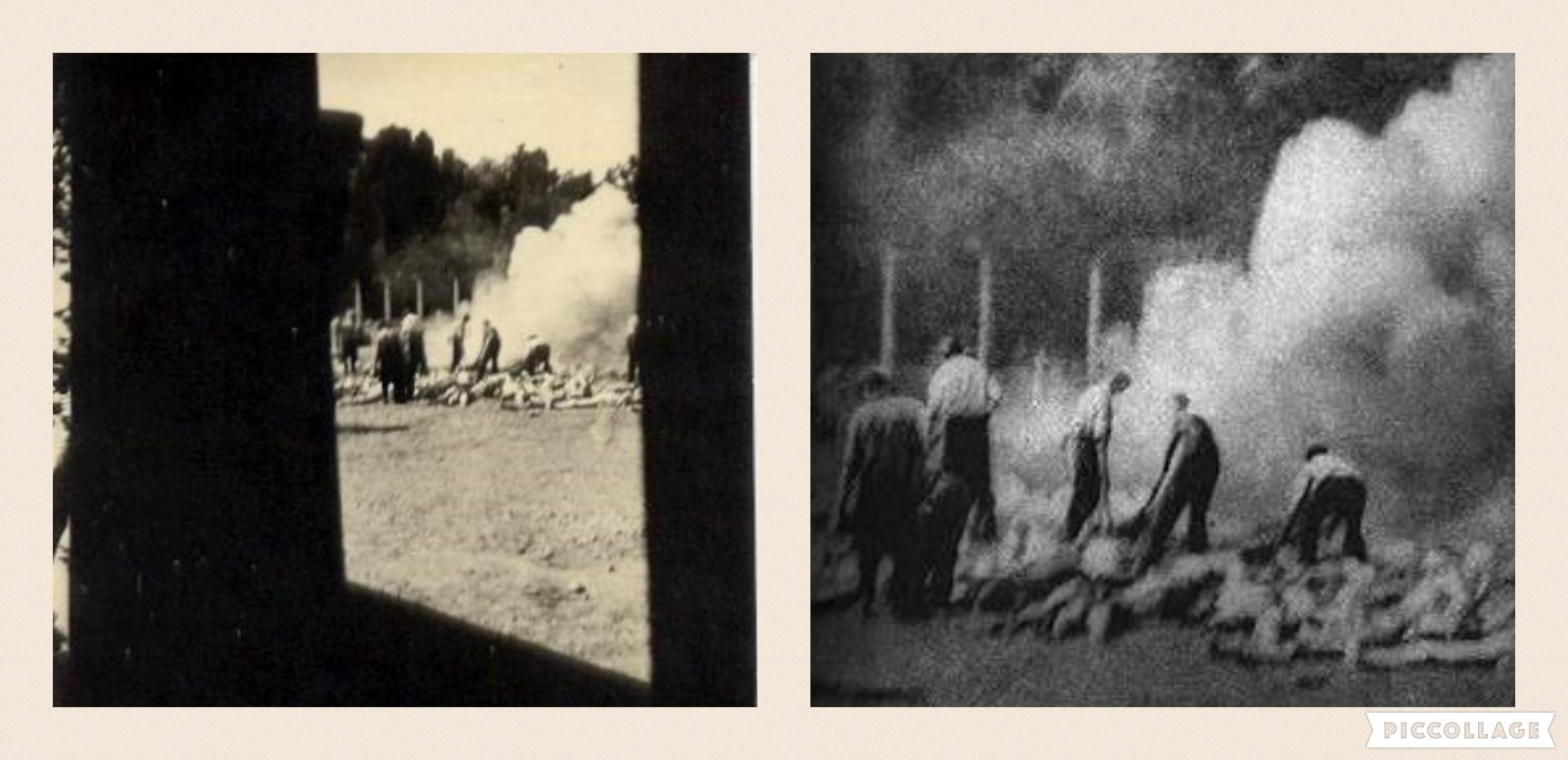

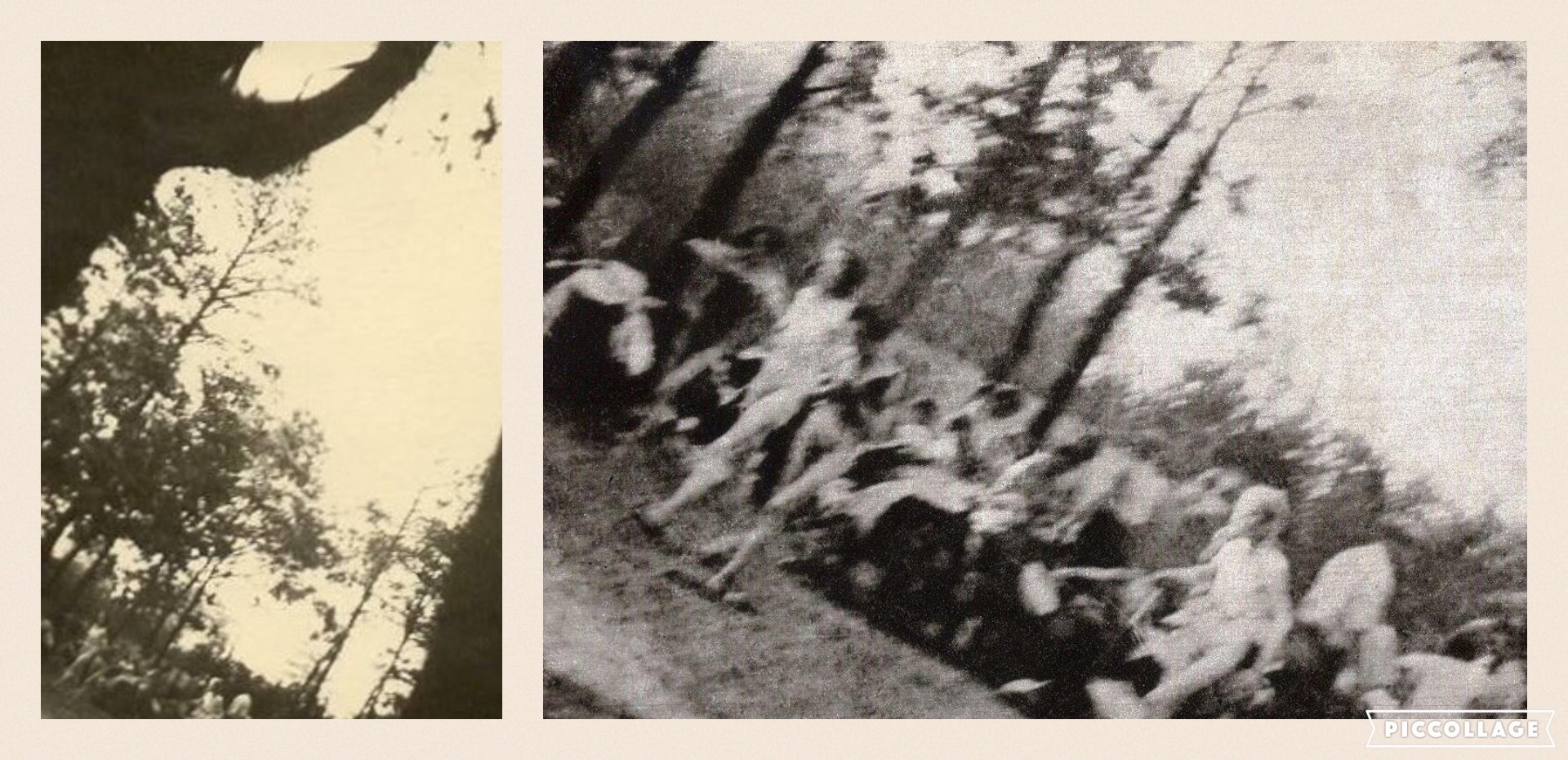

The Sonderkommando photographs from Auschwitz are four blurry photos taken secretly from inside the camp in August 1944. They are some of the only known photos in existence of events around the gas chambers. Those who have given eyewitness accounts pertaining to Auschwitz' Sonderkommando photographs usually only refer to the person behind the camera as "Alex, a Jewish prisoner from Greece". Research indicates that "Alex" was most likely Alberto Errera, a Greek naval officer who, at a later date, was shot and killed for striking an SS officer.

Two photos were taken from inside one of the gas chambers and two more photos were taken from outside. Due to the fact that these photos were taken secretly, the camera was unable to be aimed with any precision (that is why the shots are blurry and off-centered). Other members of the Sonderkommando in the camp's Crematorium V helped obtain and hide the camera, and acted as lookouts. One of the men involved, Alter Fajnzylberg, described how the photos were taken:

"On the day on which the pictures were taken ... we allocated tasks. Some of us were to guard the person taking the pictures. In other words, we were to keep a careful watch for the approach of anyone who did not know the secret, and above all for any SS men moving about in the area. At last the moment came. We all gathered at the western entrance leading from the outside to the gas-chamber of Crematorium V: we could not see any SS men in the watchtower overlooking the door from the barbed wire, nor near the place where the pictures were to be taken. Alex, the Greek Jew, quickly took out his camera, pointed it towards a heap of burning bodies, and pressed the shutter. This is why the photograph shows prisoners from the Sonderkommando working at the heap. One of the SS was standing beside them, but his back was turned towards the crematorium building. Another picture was taken from the other side of the building, where women and men were undressing among the trees. They were from a transport that was to be murdered in the gas-chamber of Crematorium V." (Testimony of Alter Fajnzylberg provided by Jewishvirtuallibrary.org).

After the photos were taken, the film was smuggled out of the camp in a tube of toothpaste by members of the Polish underground. The note that accompanied the film said:

"Urgent. Send two metal rolls of film for 6x9 as fast as possible. Have possibility of taking photos. Sending you photos of Birkenau showing prisoners sent to gas chambers. One photo shows one of the stakes at which bodies were burned when the crematoria could not manage to burn all the bodies. The bodies in the foreground are waiting to be thrown into the fire. Another picture shows one of the places in the forest where people undress before ‘showering’—as they were told—and then go to the gas-chambers. Send film roll as fast as you can. Send the enclosed photos to Tell (Teresa Łasocka-Estreicher of the Polish underground) —we think enlargements of the photos can be sent further." (Jewishvirtuallibrary.org).

Alberto "Alex" Errera and the other Sonderkommandos involved in taking and preserving these photographs are heroes. They were willing to risk their lives to let the outside world know what was going on inside of Auschwitz. They resisted the Nazis by taking and smuggling photographs right under their noses.

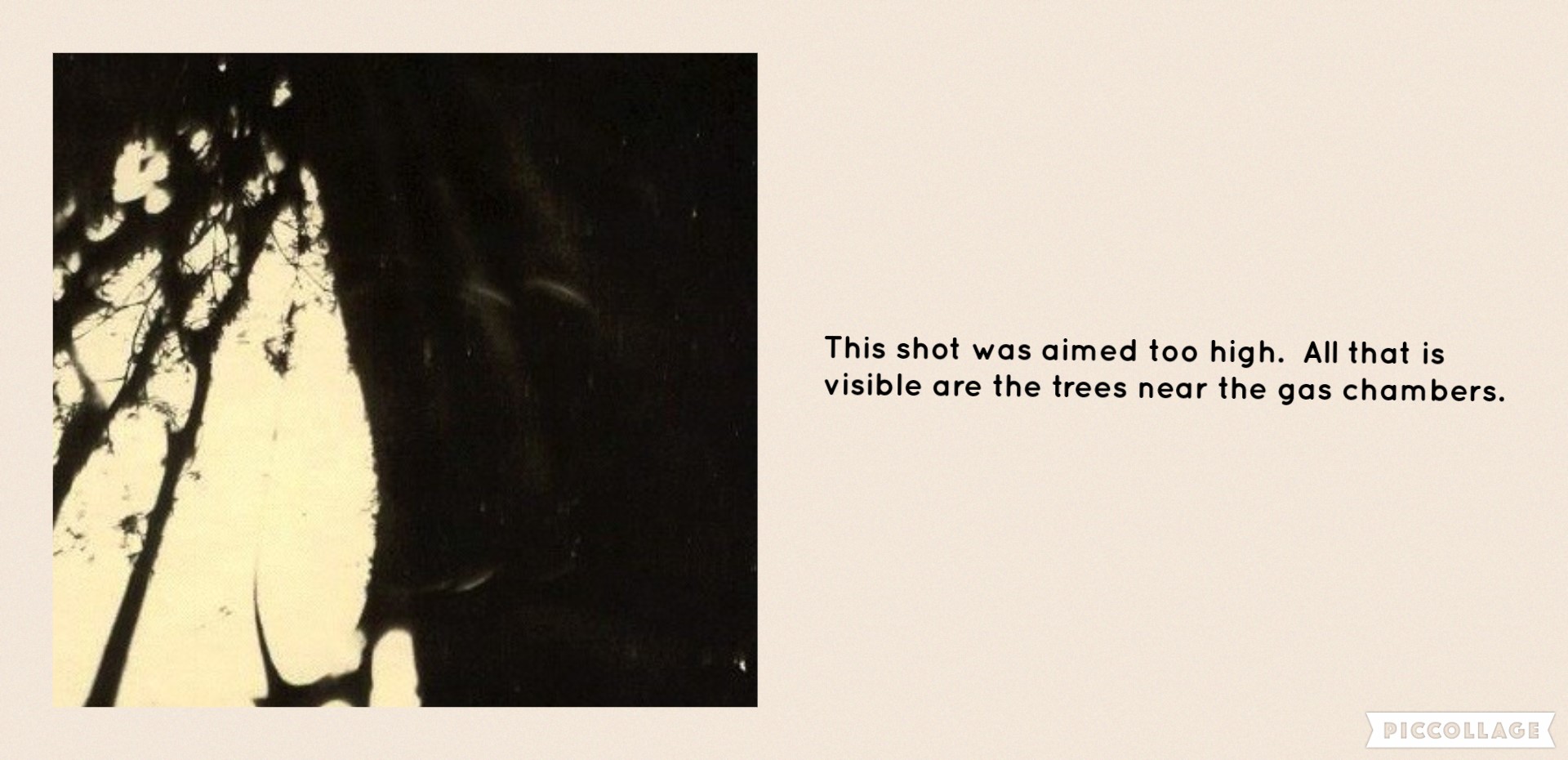

PLEASE NOTE – The Sonderkommando photographs from Auschwitz were cropped by members of the Polish underground so that the figures in the photos could be seen more clearly. Both the original and the cropped versions are available below. ↡

This photo shows piled up corpses waiting to be burned. Original photo on the left, cropped photo on the right.

This photo shows bodies being dragged into an outdoor fire pit. Original photo on the left, cropped photo on the right.

This photo shows undressed women being taken to the gas chamber. Original photo on the left, cropped photo on the right.

Due to the fact that these photos were being taken secretly using a concealed camera, this shot was accidently aimed too high. All you can see in this photo are the trees near the gas chambers.

Zvi Kadushin was born in Lithuania in 1910. He always had an avid interest in photography and in his spare time he built cameras. When WWII began and the Germans invaded, all of the Jews, including Zvi Kadushin, were forced to relocate into a fenced-in part of Kovno which came to be known as the Kovno Ghetto. The first violent attacks on the Jews of Kovno in 1941, is what made Kadushin start to secretly document life in the ghetto. It was forbidden for Jews to take unauthorized photographs of ghetto life. If the Nazis found out Kadushin had a camera and was using it to document what was happening, they would have killed him on the spot. Knowing the risks, Kadushin continued to resist the Nazis by secretly taking photographs through a buttonhole of his coat.

"Acquiring and developing film secretly outside the ghetto were just as perilous as using hidden cameras inside. Kadish received orders to work as an engineer repairing x-ray machines for the German occupation forces in the city of Kovno. Once in the city, he discovered opportunities to barter for film and other necessary supplies. He developed his negatives at the German military hospital, using the same chemicals he used to develop x-ray film, and succeeded in smuggling them out in sets of crutches." (USHMM.org).

In March 1944, Zvi Kadushin found out the Gestapo were looking for him — they had somehow discovered that he was taking illegal photographs. Kadushin buried many of his photographs, along with the negatives, in a milk can underneath his house. He then fled the ghetto and went into hiding. He photographed the liquidation of the Kovno Ghetto from the Aryan side in July, 1944. Following the liberation of Kovno, he returned to the ghetto area. He photographed what was left, including the charred remains of countless victims. Kadushin dug up the prints and negatives that he had buried and eventually made his way to American-occupied Germany to put them on display for other survivors. After some time, Zvi Kadushin moved to the United States and changed his name to George Kadish. He passed away in 1997. Today, Kadushin's photos can be seen in museums around the world, a reminder of the risks one man took to resist the Nazis and preserve the truth.

Zvi Kadushin after the liberation of the Kovno Ghetto (c. 1944).

Zvi Kadushin after the liberation of the Kovno Ghetto (c. 1944).

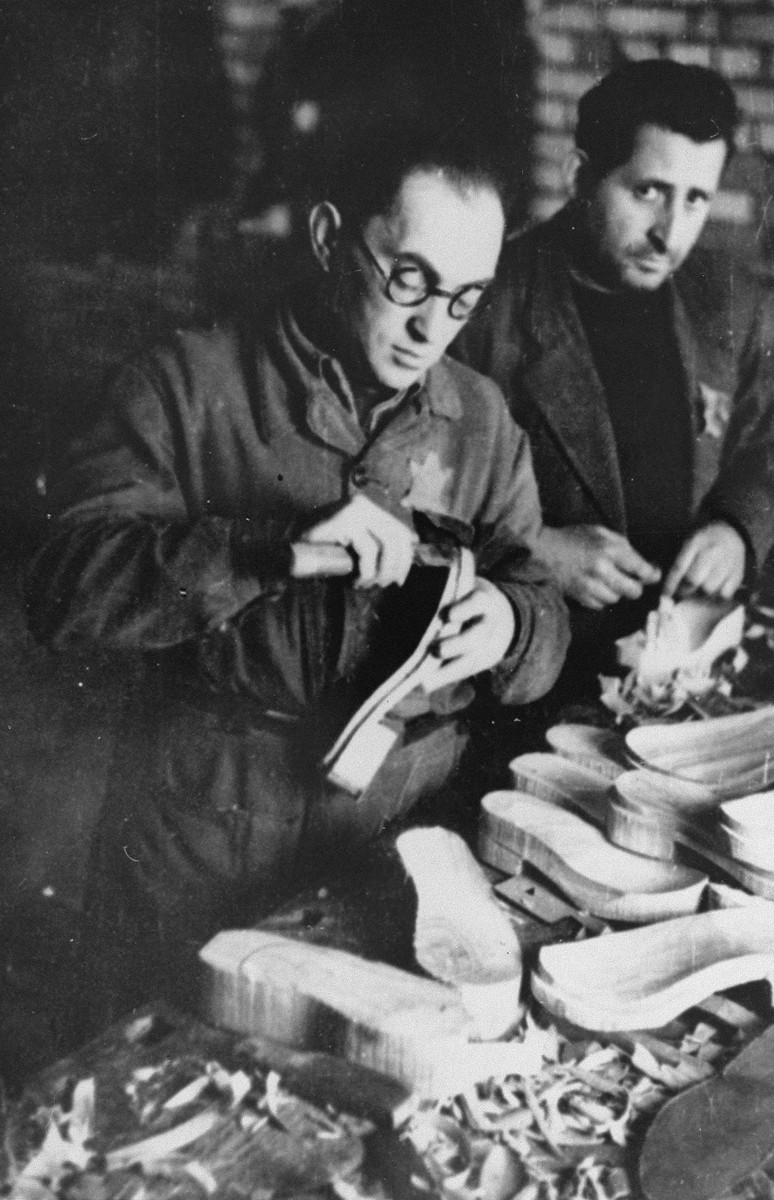

↠Two men fashioning wooden clogs in the Kovno Ghetto↞

"Following the Big Action of October 28, 1941 (a mass murder of Jews in Kovno), most of the adults remaining in the Kovno ghetto were put on forced labor, primarily in military installations outside the ghetto. In an attempt to find alternative work for those less able to withstand the harsh conditions of the labor brigades, the Jewish Council promoted the establishment of workshops in the ghetto. Women with small children and yeshiva students were also given work in the workshops. With German approval, the first workshop was opened on January 12, 1942. This was a tailoring shop to sew and repair German military uniforms. Eventually the ghetto established forty workshops, which manufactured clothing, leather goods, soap, brushes and metalwork. There was even a toy workshop that shipped its products to German children as Christmas gifts from the ghetto. The workshops, though nominally supervised by the German Stadtskommissar (the head of a town in occupied German territories), were largely run by Jews themselves who practiced considerable deception. Thus, following the children's action in nearby Siaulai (mass murder of children in 1943), large numbers of underaged laborers were given work in the Kovno workshops in order to protect them in the event of a similar action. Workshop employees were also able to funnel a large quantity of items to ghetto residents and the underground. Moshe Segalson, head of the workshops, reports that of the 4,000 aluminum cups and pots sent for repair, only 460 were returned to the German army. Jewish partisans, departing for the forests, were thus able to leave the ghetto equipped with mess kits and warm clothing courtesy of the ghetto workshops." (USHMM.org)

↠A Jewish vendor in the Kovno Ghetto↞

"Close-up of a Jewish vendor in the Kovno ghetto who was known as 'Hamster' for gathering and selling bread on the black market. A few days after this photo was taken, he was shot by the Germans." (USHMM.org).

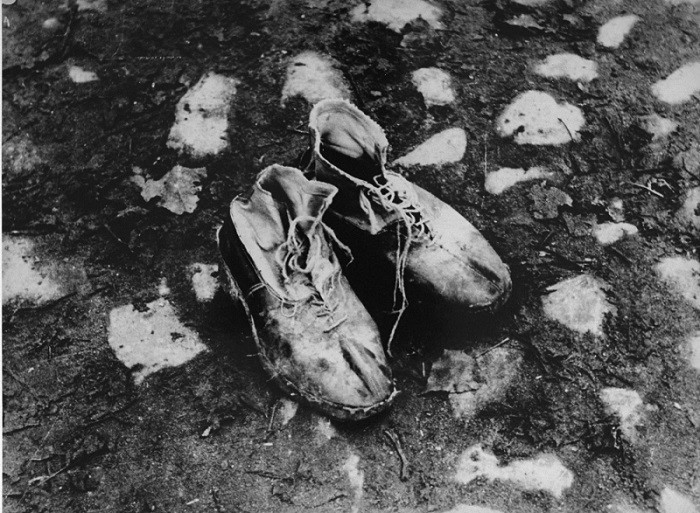

↠ "The Body is Gone" ↞

These shoes were left behind after one of the deportation acts in the Kovno Ghetto. Zvi Kadushin captioned this photo "The Body is Gone".

↠ Smoke rising from Kovno Ghetto during liquidation ↞

"The liquidation of the Kovno ghetto/concentration camp began on Saturday, July 8, 1944, three weeks before the Soviet liberation of the city. Approximately 6,100 Jews were transported over a six-day period to concentration camps: the women to Stutthof and the men to Dachau. Knowing that thousands failed to appear for the round-ups and likely remained hidden in bunkers, the SS ordered German troops to raze the former ghetto. Every house was blown up and the ruins doused with gasoline and incinerated. Thousands were either burned to death or shot trying to flee. The fires burned for a week, leaving a charred landscape of rubble and stone chimneys. Only approximately 100 Jews survived the liquidation." (USHMM.org).

↠ Ruins of Kovno Ghetto after liquidation ↞

↠Charred remains in Kovno Ghetto after liquidation↞

↠ Henryk Ross: Photographs From A Nazi Ghetto ↞

(YouTube. Courtesy, HISTORY).

Henryk Ross was born in Poland in 1910. He had a background in photography; before WWII he was a sports photographer for a Warsaw newspaper. Ross was living in Lodz, Poland in 1940 when the Germans forced all the Jews into a sealed off area of Lodz — this area became known as the Lodz Ghetto. Due to his prior photography skills, Ross was able to secure a job as one of the official photographers in the ghetto. Ross was one of the people in charge of producing identity and propaganda photographs for the Department of Statistics in the Lodz Ghetto. Thanks to his job, Ross had access to film and processing facilities in the ghetto. He began to secretly document the conditions in the ghetto, the suffering of the Jews there, and the brutality of the Germans.

"His work was an act of resistance against the prohibition of the Germans and the ghetto authorities to take pictures that were not officially approved. He hid his camera underneath his coat, opened it slightly, and snapped the photographs. Ross exposed himself to dangers and risked his life in order to take the pictures. In this fashion, he accumulated thousands of pictures that tell us what life was like in the Lodz Ghetto." (Yadvashem.org).

The liquidation of the Lodz Ghetto began in 1944. Henryk Ross buried his photographic evidence in the ground somewhere in the ghetto, hoping that someone would find it if he didn't survive.

"Just before the closure of the ghetto (1944) I buried my negatives in the ground in order that there should be some record of our tragedy, namely the total elimination of the Jews from Lodz by the Nazi executioners. I was anticipating the total destruction of Polish Jewry. I wanted to leave a historical record of our martyrdom." (Testimony of Henryk Ross provided by Yadvashem.org).

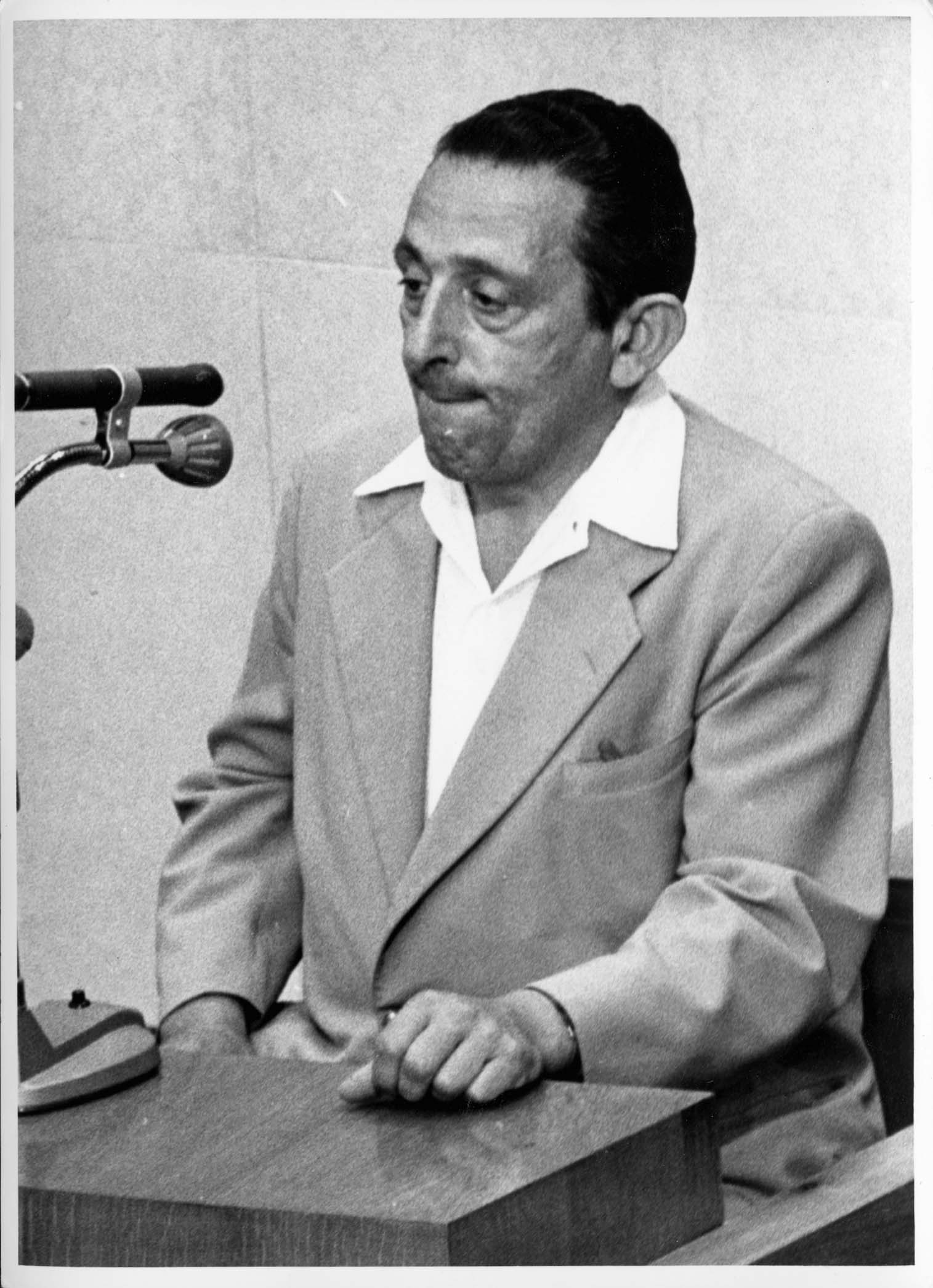

Henryk Ross survived the Holocaust. He dug up the photographs he buried after the liberation of Lodz. After WWII ended Ross eventually moved to Israel with his family. In 1961, the photographs Henryk Ross took in the Lodz Ghetto (along with his verbal testimony) were used as evidence to convict former SS officer Otto Adolf Eichmann of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes against the Jewish people. Ross passed away in Israel in 1991. Today, Ross' photos can be viewed in museums around the world.

"The photographs that Henryk Ross took that show the true conditions of the Lodz Ghetto are a testament to his bravery. Henryk Ross kept his exceptional collection and catalogued it for future generations in order for them to gain an insight into the suffering that the ghetto inhabitants faced." (Yadvashem.org).

PLEASE NOTE – Henryk Ross took many photographs of seemingly "happy" times in the ghetto, with people dressed nicely and smiling. You will not find any of these "happy" photographs on this page. Those photos are deceptive and they undermine the hardships and suffering of most of the people in the Lodz Ghetto. This page aims to preserve the truth of the Holocaust through photography, and those "happy" photos stand in stark contrast to the reality of the Holocaust.

"Having an official camera, I was able to capture all the tragic period in the Lodz Ghetto. I did it knowing that if I were caught my family and I would be tortured and killed."

- Henryk Ross

Henryk Ross' work ID card photo taken in the Lodz Ghetto. (c.1941).

Henryk Ross' work ID card photo taken in the Lodz Ghetto. (c.1941).

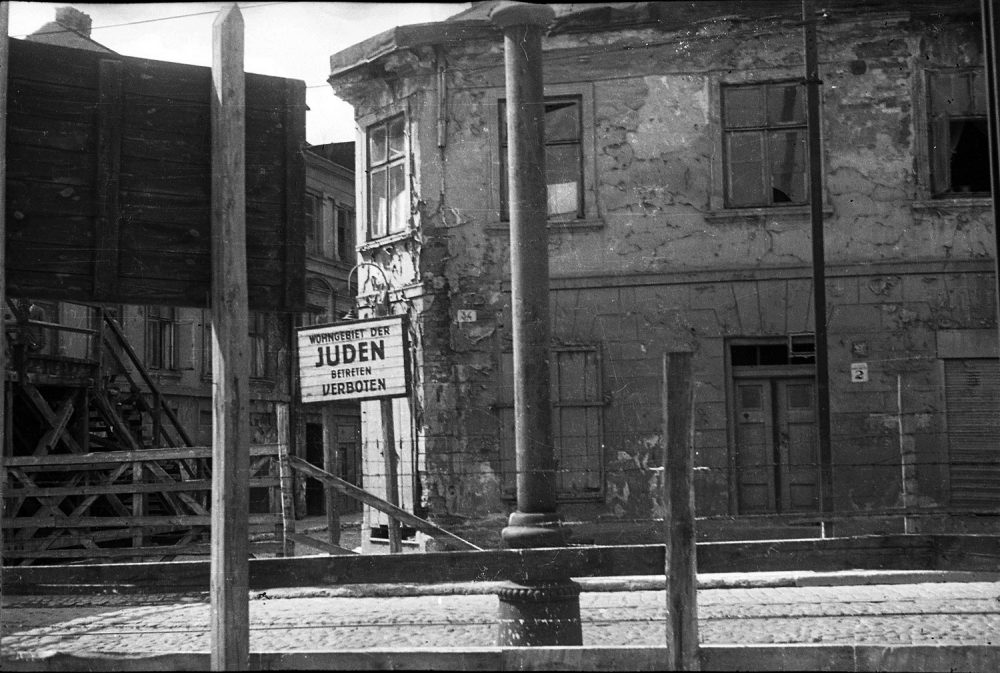

↠ “Wohngebiet der Juden Betreten Verboten” ↞

Henryk Ross' photo of a Lodz Ghetto entrance sign. Translated to English, the sign reads: “Residential area of the Jews, entry forbidden”. (WBUR. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

Henryk Ross secretly photographed this deportation in 1944. Ross described the circumstances under which he took this photograph at the Eichmann trial: "On one occasion, when people with whom I was acquainted worked at the railway station of Radegast, which was outside the ghetto but linked to it, and where trains destined for Auschwitz were standing – on one occasion I managed to get into the railway station in the guise of a cleaner. My friends shut me into a cement storeroom. I was there from six in the morning until seven in the evening, until the Germans went away and the transport departed. I watched as the transport left. I heard shouts. I saw the beatings. I saw how they were shooting at them, how they were murdering them, those who refused. Through a hole in a board of the wall of the storeroom I took several pictures." (Testimony of Henryk Ross provided by Yadvashem.org).

Henryk Ross' photo of Lodz Ghetto children being transported to the Chelmo nad Nerem death camp. (WBUR. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

Henryk Ross testifying during the Eichmann trial (c. 1961).

Henryk Ross testifying during the Eichmann trial (c. 1961).

Faye Schulman was born Faigel Lazebnik in Lenin, Poland (now Belarus) in the year 1919. She learned her photography skills from her oldest brother, Moishe Lazebnik, who worked as a professional photographer. In August 1942, the Germans killed 1,850 Jews from the Lenin Ghetto, including Faye's parents, sisters and younger brother. The bodies were thrown into three trenches that served as mass graves. They spared only 26 Jews that day, among them Faye for her photographic abilities. The Germans ordered Faye to develop their photographs of the massacre. As she developed the pictures, she was able to identify the exact trench where the bodies of her family members were…she secretly made copies for herself.

"During a partisan raid, Faye fled to the forests and joined the Molotava Brigade, a partisan group made mostly of escaped Soviet Red Army POWs.During a raid on Lenin, Faye succeeded in recovering her old photographic equipment. During the next two years, she took over a hundred photographs, developing the medium format negatives under blankets and making "sun prints" during the day. On missions Faye buried the camera and tripod to keep it safe. Her photos show a rare side of partisan activity -- one is a funeral scene where two Jewish partisans are being buried alongside Russian partisans, despite the intense antisemitism in the group." (USHMM.org).

After liberation, Faye married Morris Schulman, who was also a Jewish partisan. Faye and Morris enjoyed a prosperous life as decorated Soviet partisans, but wanted to leave Pinsk, Poland which reminded them of "a graveyard". Morris and Faye immigrated to Canada in 1948. Today, Faye’s photos can be seen in several books, documentaries, and in Holocaust museums around the world. She passed away in Toronto, Canada in April 2021. Faye Schulman remains one of the only known Jewish partisan photographers. She resisted the Nazis with a camera AND an automatic rifle; she was a courageous woman who wanted the world to know that there were Jewish people who were fighting back. She risked her life to preserve the truth of the Holocaust in the photographs she took.

Faye Schulman nee Lazebnik (c. 1938)

Faye Schulman nee Lazebnik (c. 1938)

↠ Faye Develops A Photo Of Her Family ↞

(YouTube. Courtesy, JPEF Interviews.)

Faye Schulman learning how to shoot her new automatic rifle (c. 1942).

Faye Schulman learning how to shoot her new automatic rifle (c. 1942).

Schulman with other members of the Molotava Brigade (c.1942-1943).

Schulman with other members of the Molotava Brigade (c.1942-1943).

Molotava Brigade (c. 1942).

Molotava Brigade (c. 1942).

"These are two Jews and two gentiles, all four buried in one grave together.... They fought together against the same enemy, so they are buried together." (Photo c. 1944). (Testimony of Faye Schulman provided by Jewishpartisans.org).

"I want people to know that there was resistance. Jews did not go like sheep to the slaughter. I was a photographer. I have pictures. I have proof." - Faye Schulman

Faye Schulman pictured with the same camera she used during her time in the Molotava Brigade. Picture taken by Moishe Lazebnik. (c. 1999).

Faye Schulman pictured with the same camera she used during her time in the Molotava Brigade. Picture taken by Moishe Lazebnik. (c. 1999).

↠ Faye With Her Camera ↞

(YouTube. Courtesy, JPEF Interviews.)

First off, all of the photographers discussed on this page are heroes, that is an undeniable fact. We know that these five photographers fought to preserve the truth through their photographs, however, it is also interesting to look at the photographic method each of these photographers had to use based on their individual circumstances. Wilhelm Brasse was forced to take portrait style identity photographs of inmates, and due to the clarity of these photos, the complex emotions of sadness, shock, fear, and anger that these victims of Auschwitz were feeling is almost tangible. The expressions etched on the faces of these people is testament of the brutality and despair of, what was for many of them, their final moments. Alberto Errera’s Sonderkommando photos, along with many of Kadushin's and Ross' photographs, are off-center and sometimes obstructed; it is evident that they were taken secretly and hastily by the person holding the camera. Considering that it was punishable by death for Jews to take unauthorized photographs in the ghettos or camps, these secret photographs, taken with concealed cameras, were the epitome of resistance against the Nazis. Faye Schulman’s photographic method was a little different; while she did take photographs of the events occurring around her, she was also in many of the photographs that she took. She was able to do this by placing her camera on a tripod and setting a timer. I believe she included herself in many of the photos she took because, while she wanted to photograph images of armed resistance against the Nazis, she also wanted to make it known that she was involved in that armed resistance as well.

The most important thing to remember about all of these photographers is why they fought to take and/or preserve the photographs they shot. They wanted to record the tragedy and dehumanization of the Jewish people (and the other people targeted by the Nazis). They wanted to preserve the truth of the Holocaust with undeniable evidence. They wanted the world to know that they resisted, that they fought back against overwhelming hate. In my opinion, the camera -especially in the hands of Brasse, Errera, Kadushin, Ross, and Schulman- became the most powerful weapon ever wielded against the Nazis because scars fade, but images don’t. Many of the photos taken by these five courageous photographers still survive today, preserving the truth of the Holocaust for generations to come.