Classification

Classification

There are several reasons for classification. All cultures have grouped plants and animals into categories. We all group things to make it easier to keep track. On a simple level, look at motor vehicles. They are grouped into classes of cars and trucks.

- One of the primary reasons is that there are just two many species to keep track of , We try to make sense of an extraordinary large volume of information - organize.

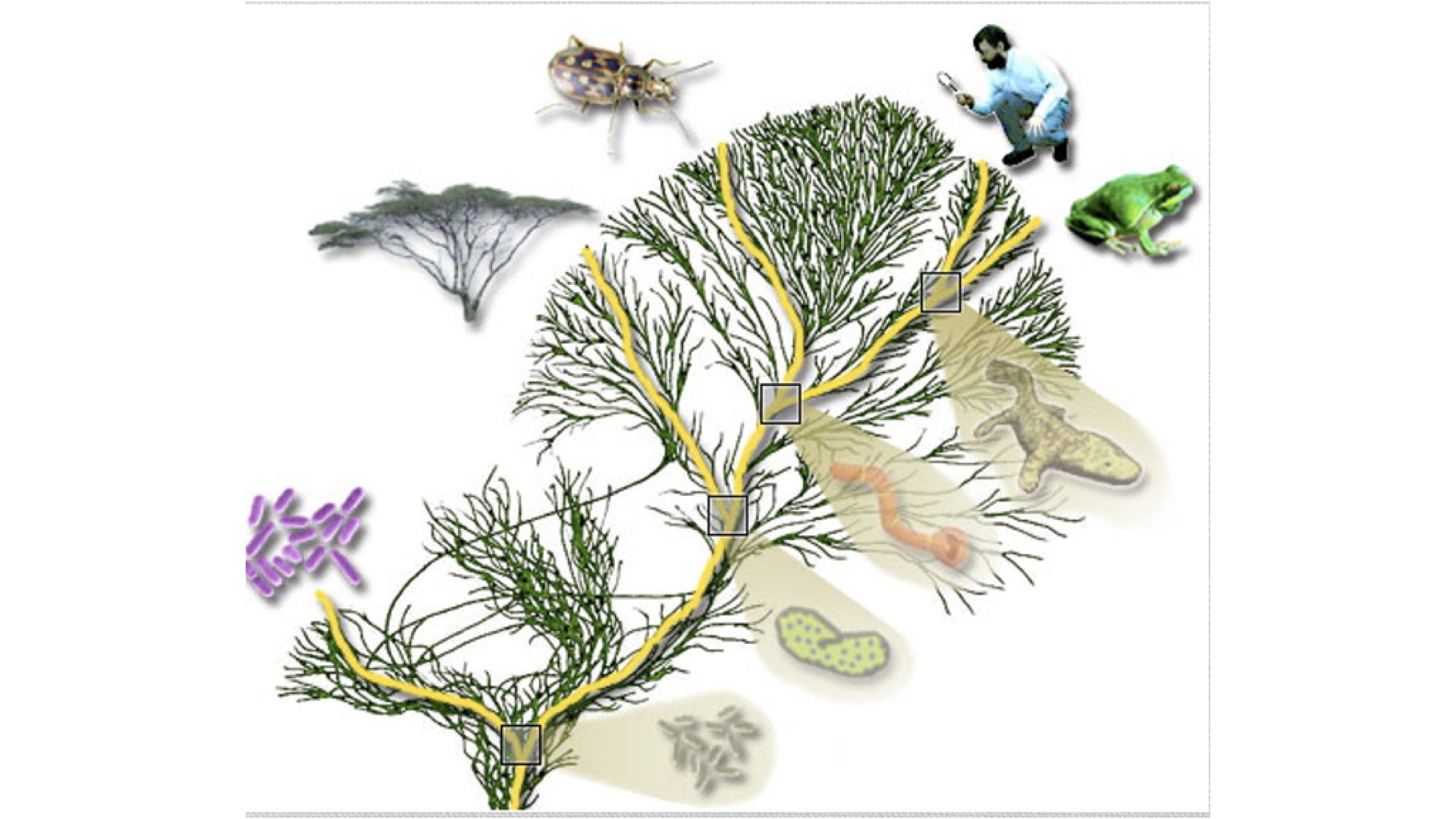

- Today, another major reason is to reflect evolutionary relationships. Evolution is the connection between species. Classifications try to ensure that evolutionary relationships between species are accurately displayed. Of course, as we learn new things about both current and past species, these relationships change and the classifications must also change.

- Classification systems help scientists place newly discovered species into correct classifications.

- Classification systems also help as identification keys.

We generally don’t pay much attention to classifi cation until our biology class makes us do it. Actually, we all use classification systems to make sense of the world around us—on a number of levels. For instance, we all refer to annoying small life forms as “bugs.” But the word “bug” doesn’t tell you much about them. They might be mosquitoes, gnats, chiggers, ants, spiders, wasps, etc. We also refer to a set of objects as “tools.” A tool may be anything from a simple wrench or screwdriver to a radial arm saw. To simply tell someone you need a tool is not sufficient. A lot more information is needed to describe any particular tool. Since biology studies the living world, it is important to try to make some sense out of the vast number of different organisms. So, we give them names and organize groups of similar organisms into categories to make them easier to talk about and understand. There is a huge difference between telling someone each of thefollowing:

- There is a life form on your arm.

- There is a bug on your arm.

- There is a small object on your arm that is moving.

- There is a black, one half-inch organism with eight legs on your arm.

- There is a black spider on your arm.

- There is a Latrodectus mactans (black widow) on your arm.

So we use classifi cation to organize the large number of living organisms into a more easily understandable body of knowledge. As an analogy, think of someone’s garage. We have all seen the inside of someone’s garage where things were just piled all over. There were all kinds of tools and other objects; but, since they weren’t organized, they were difficult if not impossible to find. Then there is Tim the Toolman’s garage. Every tool in its place—on a pegboard, with an outline of the tool on the pegboard, so you know what belongs there when the item is missing. You can find anything.

Classification is organization—something we all plan to try some day. Classification probably began as soon as humans had names for different organisms. We know that the early Greeks divided animals into three groups—those that lived on land, those that lived in the water, and those that flew. While this is certainly one way to organize our thinking about living organisms, it has limitations in its ability to group related organisms together—we all know that birds and dragonflies are not anywhere near the same organism. The same could be said for jellyfish and dolphins. Plants presented similar difficulties.

Basically, the problem is what basis to use to group organisms. The search was for a “natural” system of classification that one could use to “naturally” divide organisms into groups—such as petals or ovaries on flowers of plants or teeth or wings on animals. There was little success with this approach through the 1600s.

In the late 1700s, Carolus developed a system that used “ranks” in which to put organisms. He used descriptions (plants only to start) of the organism, either his own or others, to find similar characteristics among the plants. This led to the now familiar binomial nomenclature (genus and species) designation for each organism. In this system, each species was considered to be a model of a “perfect” type specimen that did not change—sort of like Plato’s cave and the shadows that we see. These were collected into larger groups at higher ranks. However, since the late 1800s we also understand that organisms change with time, evolve, and have ancestral relationships. So, in the twentieth and now twenty-first centuries, biologists are also focusing on the evolutionary relationships of organisms. In other words, those organisms most closely related to each other should also be classifi ed in closely related groups. Take house cats, mountain lions, and beagles. You know what they all are. Even though house cats are about the size of a beagle and frequently found in the same habitat, it is easy to see that house cats and mountain lions are more closely related than house cats and beagles. This is an evolutionary relationship. The common ancestor of house cats and mountain lions is closer than either of them with a common ancestor to both dogs and cats. Our classification system should

represent this evolutionary relationship. In fact, today, classification is almost entirely about evolutionary relationships. As we learn more about evolutionary relationships of organisms, classifi cations are rearranged to refl ect this new knowledge. These changes are also being driven by molecular levels of knowledge—DNA and proteins.

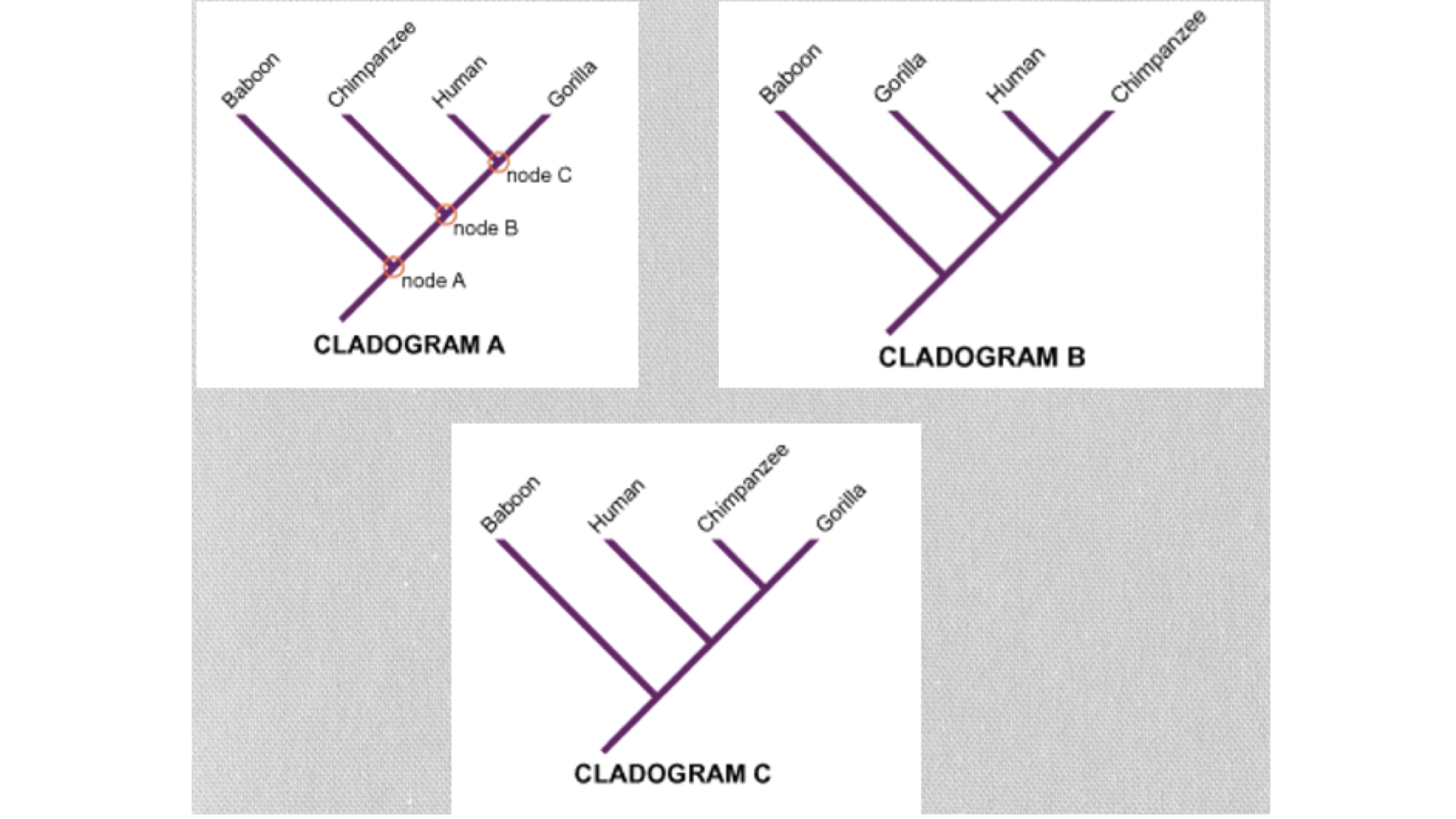

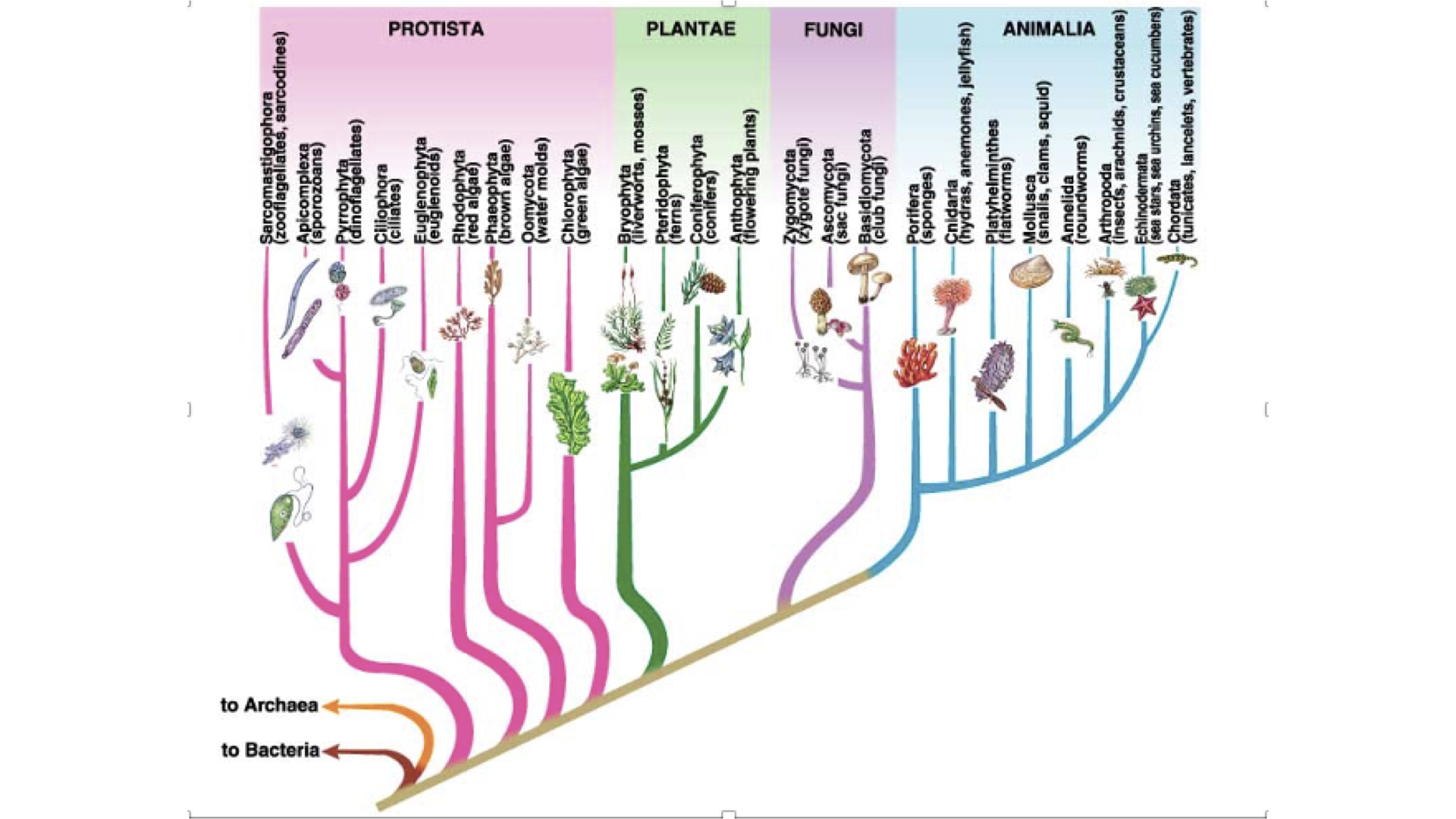

As an example, above are four species and three different ways of arranging their evolutionary relationships. Based strictly on appearance, it is not immediately obvious which of these are correct. With today's molecular data, we know that option B is more correct than the other two. This process gives us an approximate tree diagram as shown below:

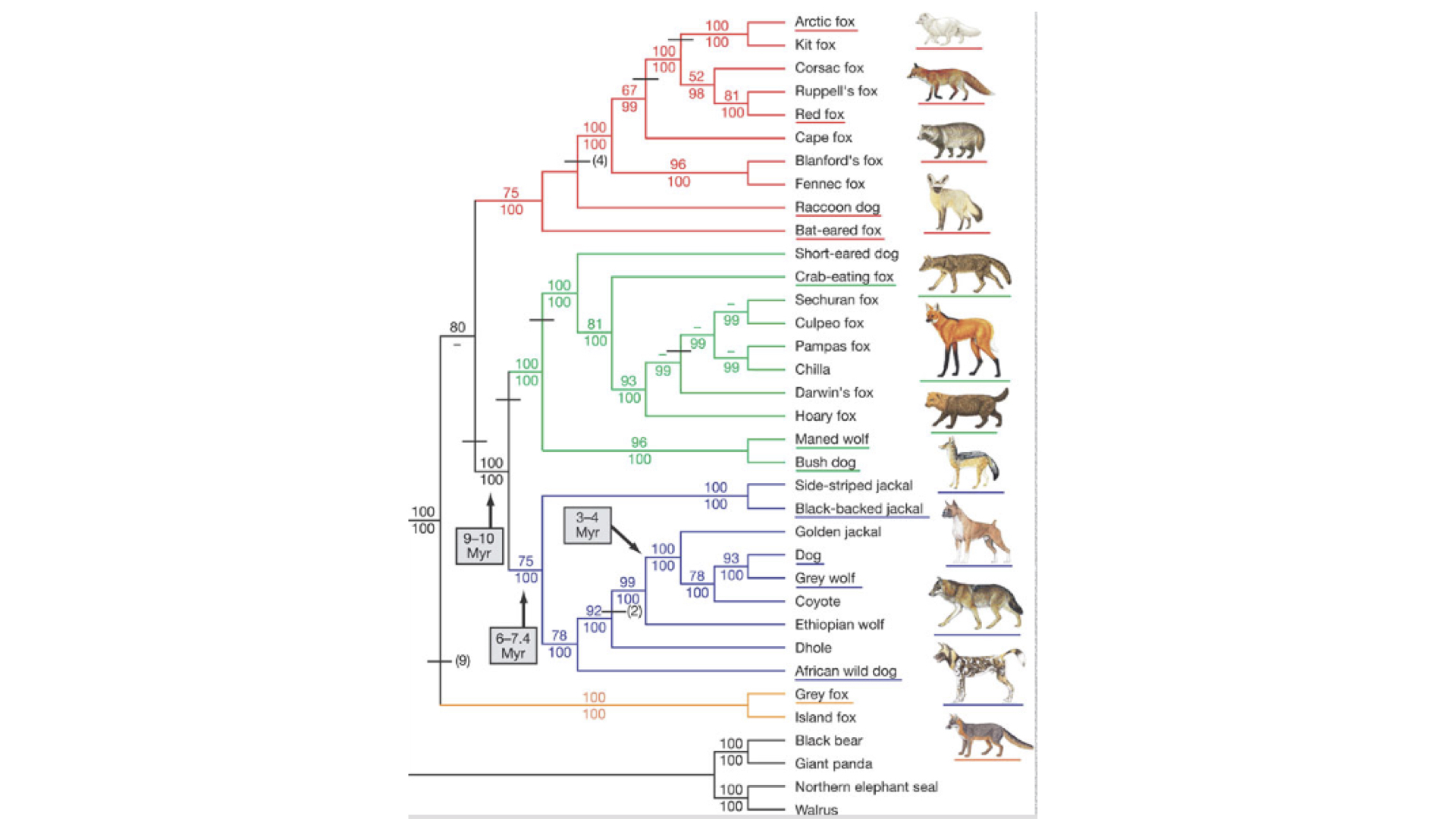

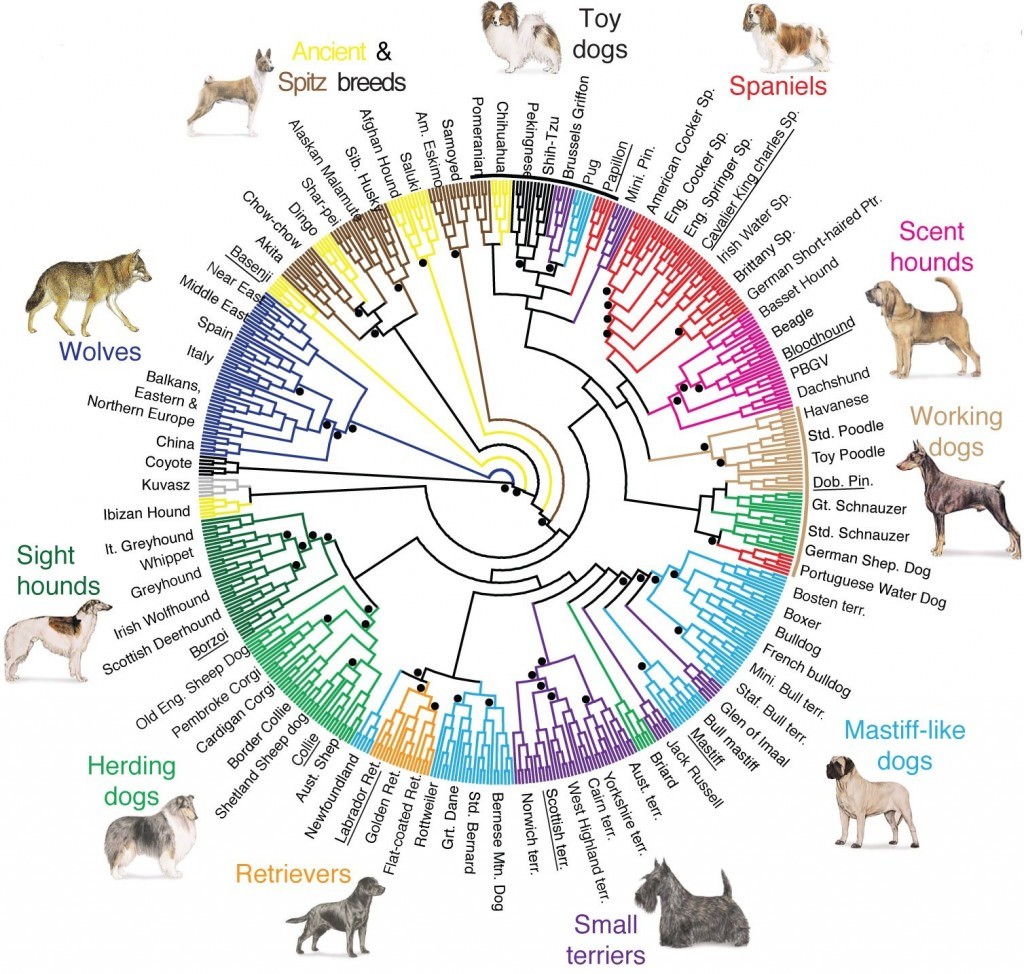

Below are two more diagrams; one for canids and one for dogs more specifically that parts from the gray wolf..

As you go through the major groups of organisms at the Domain and Phylum level, pay attention to the unique characteristics used to place organisms into the various groups. You will probably not be a taxonomist but you can at least appreciate that there is a "madness to the method" used.

On the outside chance that you are more interested in the process, I recommend the Tree of Life Web Project.