The Theory of Andragogy

The Theory of Andragogy

In another life, I was a high school math teacher and utilized many pedagogical strategies familiar to and used by many other pre-K through 12 teachers. Now as a medical software trainer at a large hospital system, I still use many of those pedagogical strategies but tend to utilize the four principles of andragogy more often than not now.

Both andragogy and pedagogy are terms of Greek origin with "paidi" meaning "child" and "andras" meaning "man" (respectively). The verb "ago" in Greek means "guide" to together:

paidi(child) + ago(guide) = pedagogy

andras(man) + ago(guide) = andragogy (Pappas, 2015)

If pedagogy is the study of education from a child-focused approach, andragogy is an adult focused teaching approach (Pappas, 2015).

At a glance, one can ask "What is the difference in educating a child versus an adult? Learning is learning!" But that cannot be more untrue as learning behaviors between adults and children are extremely different; adults also have the advantage of experience to draw from which plays a large role in their education. Readiness to learn, motivation, and many more factors impact the educational approach taken with adults compared to children. Knowing these differences between your target audience i.e. learners will make a difference in whether or not they learn. Read on to learn more about andragogy and its role and application in the technology rich 21st century.

As mentioned earlier, andragogy is the art of adult education or simplified, any form of adult education. German educator Alexander Kapp first used the term andragogy in 1833. American adult education expert Eduard Lindeman continued to spread the idea of andragogy but it is Malcolm Knowles, considered the father of andragogy, who in 1970 made the first attempt to categorize and describe adult education. It was actually under the guidance of Lindeman and Knowles was first introduced to andragogy and adult education; as a result, Knowles noted he was "so excited" that it "became my chief source of inspiration and ideas for a quarter of a century" (Smith, 2002).

Similar to those before him in the field of andragogy, Knowles indicated that adult and children students learned very differently. In 1980, he made four assumptions about adult learners; considering how you view each assumption, there can be as many as six assumptions. However, the four he introduced in 1980 are:

- Self-concept: as a learner matures, he/she moves from a dependent personality to that of an independent, self-directing one.

- Adult learner experience: as a learner matures, he/she acquires a continually growing collection of experience that becomes a valuable resource for learning.

- Readiness to learn: as a learner matures, his/her readiness to learn increases in accordance with the development tasks of his/her roles.

- Orientation to learning: as a learner matures, the application of knowledge is sooner than later, and learning moves from subject-centric to problem-centric (Pappas, 2015).

In 1984, Knowles added a fifth assumption that as learners mature, motivation is internal.

Also in 1984, Knowles introduced his four principles of andragogy. Again, depending on how you break down Knowles' assumptions and principles, there can be up to six. Moving forward, I will categorize them into the below four principles as was also described by Christopher Pappas of elearningindustry.com. Regardless of the number of assumptions, principles, or categorizations, all of the foundations of Knowles' andragogy theory can be seen. His four principles are:

- Adults need to be actively involved in the planning and evaluation of their instruction i.e. buy-in which produces more faith and confidence in the adult students.

- The basis of learning activities are experiences including mistakes.

- Subjects that have immediate relevance to their personal lives or impact their jobs interest adults the most.

- Adult learning is problem-centric and not content-centric (Pappas, 2013).

Learning Theorist: Malcolm Knowles - Andragogy

According to Christopher Pappas, Knowles established five assumptions about adult learners and four principles by which to teach adults (2013). The assumptions and principles blur into each other depending on where you stand but I cannot say that I disagree with any other categorizations I've seen elsewhere. However, I have designed this lesson based on the four principles Pappas stated but the above video explores six. The overlap is clear and further search will produce resources with varying numbers of principles. Here are the four introduced in 1980:

- Adults need to be actively involved in the planning and evaluation of their instruction.

- The basis of learning activities are experiences including mistakes.

- Subjects that have immediate relevance to adults' personal lives or impact their jobs interest them the most.

- Adult learning is problem-centric and not content-centric (2013).

In a nutshell, adults need to be active participants of their education whether it is the design and development or the instructional aspect itself. This creates more buy-in and faith in the curriculum. Furthermore, with so much more experience to draw from to contribute to the planning and evaluation of their education, doing so will give the curriculum value thus making it more meaningful - not just in principle but in the adult's personal and professional life. Lastly, adult learning tends to be more problem-centric i.e. what is the problem and how can it be solved. For example, how can the last year's third quarter trends and profits predict this year's trends (problem focused) for an adult, accounting student instead of what is 15% of $25 for a high school math student.

Andragogy: Adult Learner Principles

Pappas, C. (2014). Instructional design models and theories: Computer-based instruction theory. Retrieved from https://elearningindustry.com/computer-based-instruction-theory.

Pappas, C. (2015). Pedagogy vs andragogy in eLearning: Can you tell the difference? Retrieved from https://elearningindustry.com/pedagogy-vs-andragogy-in-elearning-can-you-tell-the-difference.

Pappas, C. (2013). The adult learning theory – andragogy – of Malcolm Knowles. Retrieved from https://elearningindustry.com/the-adult-learning-theory-andragogy-of-malcolm-knowles.

Smith, M. K. (2002). Malcolm Knowles, informal adult education, self-direction and andragogy. The encyclopedia of informal education. Retrieved from https://infed.org/mobi/malcolm-knowles-informal-adult-education-self-direction-and-andragogy/.

Malcolm Knowles (Smith, 2002)

Malcolm Knowles (Smith, 2002)

Malcolm Shepherd Knowles was born in 1913 in Montana to loving parents; he said of his father that he "gave me the feeling that he respected my mind" (Smith, 2002). After high school, he attended Harvard where he met his wife Hulda before gaining employment with the new National Youths Administration (NYA) in Massachusetts. Here, he met and worked with leading American education expert Eduard Lindeman who took him under his wings (2002). Knowles read Lindeman's Meaning of Adult Education which he reacted to with "I was so excited in reading it that I couldn't put it down. It became my chief source of inspiration and and ideas for a quarter of a century" (Smith, 2002). Knowles has originally planned a career in the Foreign Service but this was a pivotal turning point in his life leading him towards education, specifically adult education, instead.

While completing his master degree at the University of Chicago, Knowles worked as the director of adult education at Central Chicago YMCA. During his time at the University of Chicago, he came to understand what it meant to get "turned on" to learning - to be a facilitor of learning rather than a teacher (2002). His master thesis laid the groundwork for his first book Informal Adult Education in which he explained his belief in the difference between formal and informal education.

After the University of Chicago and the Central Chicago YMCA, Knowles stayed close to education such as with his executive director position at the newly formed Adult Education Association of the USA, his tenured associate professorship of adult education at Boston University, and his involvement with the non-profit group National Training Laboratories that focused on adult education (2002). During this time, he published several books including The Modern Practice of Adult Education. Andragogy versus pedagogy; this detailed the difference in learning between adult and children. This also included the assumptions and principles mentioned earlier. He later revised and released this book again under the new title In The Modern Practice of Adult Education; From Andragogy to Pedagogy (2002). Other publications to follow were The Adult Learner. A neglected species, Self-Directed Learning. A guide for learners and teachers, and Andragogy in Action. Applying modern principles of adult education. Later, The Making of an Adult Educator. An autobiographical journey detailing Knowles' own personal reflections on his personal and personal life was published. He retired in 1979 and passed away on Thanksgiving day in 1997 but is credited for many firsts. He's credited as the first to attempt a comprehensive theory of adult education as well as the first to chart the adult education rise and movement (2002).

In 1950, Knowles published his first book Informal Adult Education which detailed his belief in the difference between formal and informal education. Knowles believed information education to be any gained from associations or clubs or any environment that provided opportunities for a person to practice and refine skills/knowledge they already had and knew (Knowles, 1950). Formation education was that provided by institutions of learning like high school, universities, trade schools, etc, where students participated for grades and credit (1950).

In 1970, he published The Modern Practice of Adult Education. Andragogy versus pedagogy in which he discusses the difference between adult and children education, stating that both groups learn very differently. His four assumptions were included in this publication as well as suggestions on how to organize, administer, design, and manage learning activities for adults (Smith, 2002).

In 1980, after being challenged with evidence that andragogy wasn't always the best fit for adult education nor was pedagogy always the best fit for children, Knowles revised and republished his 1970 book under the adjusted title In the Modern Practice of Adult Education; From Andragogy to Pedagogy (2002). He agreed with critics and added a 5th assumption about adult learners; furthermore, he established his 4 principles of adult education (as previously discussed). The most outstanding conclusion of this publication was that andragogy should be considered learner focused as adults have experience and self-direct whereas children do not yet have that experience to draw from to apply to their education and require the direction of an instructor (2002).

Knowles published several more books throughout his career including his autobiographical book The Making of an Adult Educator. An autobiographical journey in 1989.

With more adults returning to school and the option of remote education becoming more available, Knowles' theory of andragogy coupled with computer-based instruction (CBI) is a great marriage that will produce effective instructional program.

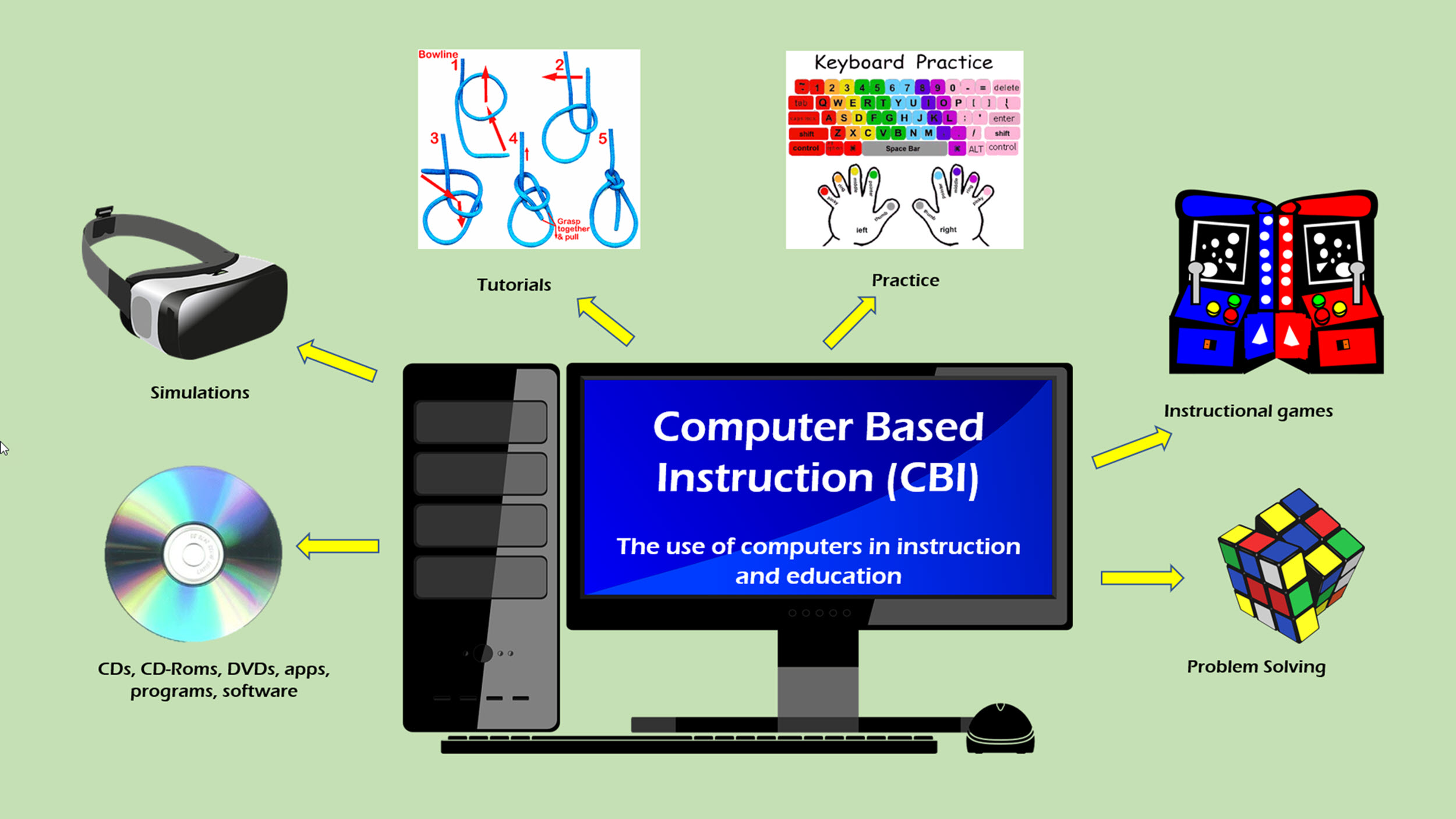

Computer-based instruction (CBI) which is often referred to as computer-assisted instruction is any education that uses a computer or any other technology/applications/software accessible through such a device (Pappas, 2014).

Various types of CBI strategies are seen in the below graphic but through these tools (among many others), all of Knowles' principles of andragogy can be easily implemented to create an effective instructional program.

Imagine a hospital/health organization that is implementing a new GI specific software. All GI staff will need to be trained but to simplify this example, the focus will be on GI nurses training, designing and developing their instructional program, testing, assessing, evaluating, and more using Knowles' theory of andragogy and CBI.

Principles 1 and 2 of the andragogy theory are closely related so they will be combined to help design the new GI nurse instructional program. Therefore: Adults should be a part of the planning and evaluation of their education contributing based off of their own personal experiences, both successes and failures.

To ensure the nurses are part of the planning and evaluation of their education, the training and instructional design team requests volunteer nurses (SMEs) who assist in planning the instructional program. This requires (but is not limited to)

- Determining the topics to be trained

- Determining the topics that can be trained in ILT and those that can be accomplished via CBI e.g. eLearnings, online reviews, assessments, etc.

- Determining the various types of CBI strategies and activities to utilize versus those that are not as applicable (e.g. pre-req eLearnings and formative assessments are appropriate for CBI delivery through videos and online games but the formative assessment may be better delivered via in-person performance assessment instead of CBI approach).

- Request that SMEs and additional volunteer nurses not originally part of the planning/developing (perhaps Super Users) be a part of the testing (evaluation). This could involve:

- Attendance in pilot testing ILT that include CBI instruction/review (e.g. exercise books with activities/scenarios that are completed in an online training environment)

- Provide feedback from pilot testing to evaluate, assess, and enhance the current instructional program.

Principles 3 and 4 can also be combined as they work well together. Therefore: Adults are interested in learning topics that most pertain to their immediate like, personal and professional, and more often than not, these are problem centered instead of content-centered.

To apply these principles, as mentioned above, SMEs will assist in determining the topics that need to be taught that are most closely pertinent to real-life i.e. GI procedure documentation. This can include:

- Checking in patient to procedure

- Documenting the start of the procedure

- Documenting scope in/out

- Specimen collection

- Documenting supplies, equipment, implants, etc

- Document timeouts, etc

However, nurse training would not include any topics like scheduling or discharge as this is left to other staff. With the SME’s knowledge, they can pinpoint the exact topics that GI nurses can relate to and therefore, see the value of their education in the instructional program.

After determining real-life scenarios/topics to include in the instructional program, the scenarios can be designed to be problem-centric

All of the above are example strategies to apply the principles of the andragogy theory to 21st century education.

Quiz: A lesson quiz will be available on (date) after all material on this page has been reviewed.

Final Assessment: Select a topic for which you will plan two instructional programs. It is not necessary to design them. One will be for adult learners using the learning theory of andragogy. The other will be for middle schoolers using a theory of your choice or you may use the theory of andragogy to plan the middle school program as well.

Example topic: how to find percent of a larger value.

Adult learners using andragogy: plan instructional program on calculating interest accrued on a loan or dividend on stocks.

Middle school students using learning theory of your choice: plan instructional program on percentages of red, blue, yellow, orange, and green M&Ms in a fun size pack.

After planning an instructional program for each, use the following to construct a 3-4 page paper. Please cite references accordingly.

- Give a brief description of each program including the theory used in each, the design models, and the strategies/tools/activities used (2 paragraphs).

- In one paragraph of the paper, discuss why you chose the learning theory you used to design the middle schoolers' percent lesson. If you chose a theory other than andragogy, why? If you chose to design the middle school program with andragogy, why?

- Compare and contrast the two program. Could the instructional program for the adult learners be applicable, effective, and beneficial for the middle schoolers? How about the other way around? Why or why not?

- Based on the reading and your own planning for this paper, do you agree with Knowles' assumptions of adult learners? Are they are applicable only to adults or do you believe they can be applied to younger learners? Explain.

Include an introduction and closing paragraph. Include references.

My personal belief of instructional design is applicable to both children and adult learners.

I believe instructional design should first begin by identifying the target audience, their needs, and the topic. This will impact the learning theory (or theories) and instructional design model (or models) utilized. For example, andragogy may not be the most fitting to teach a group of fifth graders about fractions and percentages as these learners will have very littelr fractions/percentage experiences to draw from. But for adults returning to school and taking an introductory math course, andragogy would be more appropriate.

From this point on, overall I believe instructional design should include an instructional/demonstration component. In other words, an expert or teacher should explain and demonstrate. In the example of fifth graders learning about fractions, a teacher should explain what common denominators are and then demonstrate how to find them. The same is true for adult learners.

Instruction and demonstration is followed by guided practice opportunities for the students. The instructional design can present this as a traditional paper and pencil worksheet. Or it can be a fun review game online. For example, two numbers can be presented like 2 and 5 which a grid below with possible common denominators display for the student to choose. Upon choosing a correct common denominator, the value is replaced by a star or something fun. Once a student connects a row of three common denominator stars, they "level" up. While it is a game, it is still educational; it ties a new concept back to a familiar situation (online games) while still promoting learning.

The student will continue to practice with guidance decreasing. The instructional design should provide a variety of strategies and tools that accommodates multiple learning styles and needs. But through these different tools, students can continue to practice and formative assessments are performed. They can be formal (graded as with quizzes) or informal (as with the online review game). These assessments provide feedback for correction and progress.

Finally, the instructional design will include a final, summative assessment providing the student an opportunity to demonstrate mastery of the new topic. Again, this component can be traditional paper and pencil, online, a performance assessment, a written or oral assessment; as before, a variety should be offered.

It is my belief that except for a few exception, instructional design overall for all audience types, topics, learning theories, or design models should include the above components for maximum learning.

With many learning theories to choose from, it is important to know your target audience before selecting one. By the same token, more than one learning theory can be applicable to a target audience. In my line of work, I find that andragogy and cognitivism work very well together.

However, in reviewing Malcolm Knowles' theory of andragogy, his principles are very applicable to adult learners and perhaps even some to young learners. Often we think of education as for the young, from pre-K to high school at the minimum; much research has been completed for the younger students. Yet, until Knowles' and the adult education movement, that arena had not been considered and a distinction in learning styles and needs was not identified. Fortunately, thanks to Malcolm Knowles and his theory of andragogy, a very helpful foundation was laid for designing education for adults.