Chapter 2: Goal Setting & Motivation

Chapter 2: Goal Setting & Motivation

Some people are goal oriented and seem to easily make decisions that lead to achieving their goals, while others seem just to “go with the flow” and accept what life gives them. While the latter may sound pleasantly relaxed, moving through life without goals may not lead anywhere at all. The fact that you’re in college now shows you already have the major goal to complete your college program.

Many people have no goals or have only vague, idealized notions of what they want. These notions float among the clouds in their heads. They are wonderful, fuzzy, safe thoughts such as “I want to be a good person,” “I want to be financially secure,” or “I want to be happy.”

Generalized outcomes have great potential as achievable goals. When we keep these goals in a nonspecific form, however, we may become confused about ways to actually achieve them.

Make your goal as real as a finely tuned engine. There is nothing vague or fuzzy about engines. You can see them, feel them, and hear them. You can take them apart and inspect the moving parts.

Goals can be every bit as real and useful. If you really want to meet a goal, then take it apart. Inspect the moving parts—the physical actions that you will take to make the goal happen and fine-tune your life.

There are many useful methods for setting goals. Experiment and modify as you see fit

An important part of being a successful student is defining your goals and developing a plan to meet those goals. Your goals are the overarching principles that help guide your decisions and help you make your plan for success. Goals are broad, general ideas about what you want to accomplish.

Objectives then, are the smaller, more defined steps you take to meet your goals. Objectives are more specific than goals. They must be measurable. For example, the objective “to learn more about project management” is not measurable. How would you determine if you met that objective?

Objectives should be realistic as well. For example, let’s say you set the objective of taking five classes per term for the next two years to meet your goal of graduating with a bachelor’s degree in project management. However, you also have a full-time job, which requires you to travel, and three children under the age of five to care for. Would this be a realistic objective? Likely not.

The first step of setting and attaining appropriate goals is to define the areas in which you want to create goals.

An important part of setting goals is to figure out the areas of your life where you can set goals. You should write goals in several areas of life. People who set goals in only one area of life— such as their career—may find that their personal growth becomes one-sided. They might experience success at work while neglecting their health or relationships with family members and friends.

To avoid this outcome, set goals in a variety of categories. Consider what you want to experience in these areas:

- Education

- Career

- Finances

- Family life or relationships

- Social life

- Spirituality

- Health

Add goals in other areas as they occur to you. Below is a set of questions we can ask ourselves at any turn to help focus on personal goals:

- What are my top-priority goals?

- Which of my skills and interests make my goals realistic for me?

- What makes my goals believable and possible?

- Are my goals measurable? How long will it take me to reach them? How will I know if I have achieved them?

- Are my goals flexible? What will I do if I experience a setback?

- Are my goal controllable? Can I achieve them on my own?

- Are my goals in sync with my values?

As you move through your college career, make a point to ask these questions regularly.

Not all goals can or should be accomplished in the same time frame. As you create your plan of setting and attaining goals and to get a comprehensive vision of your future, include the following time frames:

- Long-term goals. Long-term goals represent major targets in your life. These goals can take 5 to 20 years to achieve. In some cases, they will take a lifetime. They can include goals in education, careers, personal relationships, travel, or financial security—whatever is most important to you.

- Mid-term goals. Mid-term goals are objectives you can accomplish in 1 to 5 years. They include goals such as completing a course of education, paying off a car loan, or achieving a specific career level. These goals usually support your long-term goals.

- Short-term goals. Short-term goals are the ones you can accomplish in a year or less. These goals are specific achievements, such as completing a particular course or group of courses, hiking down the Appalachian Trail, or organizing a family reunion.

Setting your goals to include long-term, mid-term, and short-term time frames will not only help you create a more comprehensive plan but also allow you to more easily identify your accomplishments along the way.

Once you have defined your goals and set the time frame for each of your goals, you are ready to create your plan. Your plan should have goals in several areas of your life and include short-term, mid-term, and long-term goals. To create a plan that is achievable, make sure you write it down.

Having goals you talk about or that only exist in your mind may not give you the motivation you need to attain them.

In addition, once you create your plan, you want to take immediate action to increase your odds of success. Decrease the gap between stating a goal and starting to achieve it. If you slip and forget about the goal, you can get back on track at any time by doing something about it.

One of the most important things to do when creating your goals is to write down your goals. Writing down your goals greatly increases your chances of meeting them. Writing exposes undefined terms, unrealistic time frames, and other symptoms of fuzzy thinking.

One idea to keep track of your goals is to write each one on a separate 3 × 5 card or type them all into a document on your computer or your phone. Update your list as your goals change.

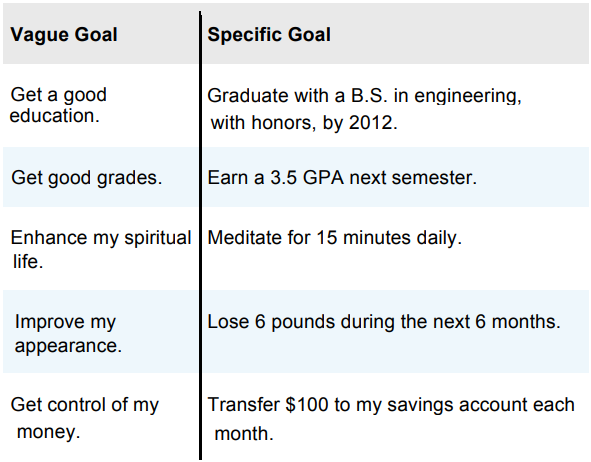

In addition to writing down your goals, make sure your goals are specific. Make clear what actions are needed or what results are expected. Consider these examples of vague goals and specific goals. Which goals are written in a way that is measurable and realistic?

From "Setting and Attaining Goals" in OpenNow College Success. Authored by Cengage Learning. Provided by: CEngage. Available at: https://oercommons.s3.amazonaws.com/media/editor/179572/CengageOpenNow_CollegeSuccessNarrative.pdf License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, available at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

When stated specifically, a goal might look different to you. If you examine it closely, a goal you once thought you wanted might not be something you want after all. Or you might discover that you want to choose a new path to achieve a goal that you are sure you want.

Motivation is an important part of being a successful student. There are at least two ways to think about motivation. One is that the terms self-discipline, willpower, and motivation describe something missing in ourselves. We use these words to explain another person’s success—or our own shortcomings: “If I were more motivated, I’d be more successful in school.”

The other approach to thinking about motivation is to stop assuming that motivation is mysterious, determined at birth, or hard to come by. Motivation could be something that you already possess—the ability to do a task even when you don’t feel like it. This is a habit that you can develop with practice.

Promise it. Motivation can come simply from being clear about your goals and acting on them. Say that you want to start a study group. You can commit yourself to inviting people and setting a time and place to meet. Promise your classmates that you’ll do this, and ask them to hold you accountable. Self-discipline, willpower, and motivation—none of these mysterious characteristics has to get in your way. Just make a promise and keep your word.

Befriend your discomfort. Once you’re aware of your discomfort, stay with it a few minutes longer. Don’t judge it as good or bad. Accepting discomfort robs it of power. It might still be there, but in time it can stop being a barrier for you. Discomfort can be a gift—an opportunity to do valuable work on yourself. On the other side of discomfort lies mastery.

Change your mind—and your body. You can also get past discomfort by planting new thoughts in your mind or changing your physical stance. For example, instead of slumping in a chair, sit up straight or stand up. Get physically active by taking a short walk. Notice what happens to your discomfort.

Work with your thoughts. Replace “I can’t stand this” with “I’ll feel great when this is done” or “Doing this will help me get something I want.”

Sweeten the task. Sometimes it’s just one aspect of a task that holds you back. You can stop procrastinating merely by changing that aspect. If distaste for your physical environment keeps you from studying, for example, then change that environment. Reading about social psychology might seem like a yawner when you’re alone in a dark corner of the house. Moving to a cheery, well-lit library can sweeten the task.

Turn up the pressure. Sometimes motivation is a luxury. Pretend that the due date for your project has been moved up 1 month, 1 week, or 1 day. Raising the stress level slightly can spur you into action. In that way, the issue of motivation seems beside the point, and meeting the due date moves to the forefront.

Turn down the pressure. The mere thought of starting a huge task can induce anxiety. To get past this feeling, turn down the pressure by taking baby steps. Divide a large project into small tasks. In 30 minutes or less, you could preview a book, create a rough outline for a paper, or solve two or three math problems. Careful planning can help you discover many such steps to make a big job doable.

Ask for support. Other people can become your allies in overcoming procrastination. For example, form a support group and declare what you intend to accomplish before each meeting. Then, ask members to hold you accountable. If you want to begin exercising regularly, ask another person to walk with you three times per week. People in support groups, ranging from Alcoholics Anonymous to Weight Watchers, know the power of this strategy.

Compare the payoffs with the costs. Skipping a reading assignment can give you time to go to the movies. However, you might be unprepared for class and have twice as much to read the following week. Maybe there is another way to get the payoff (going to the movies) without paying the cost (skipping the reading assignment). With some thoughtful weekly planning, you might choose to give up a few hours of television and end up with enough time to read the assignment and go to the movies.

Heed the message. Sometimes lack of motivation carries a message that’s worth heeding. An example is the student who majors in accounting but seizes every chance to be with children. His chronic reluctance to read accounting textbooks might not be a problem. Instead, it might reveal his desire to major in elementary education. His original career choice might have come from the belief that “real men don’t teach kindergarten.” In such cases, an apparent lack of motivation signals a deeper wisdom trying to get through.

At times, unexpected events and challenges can get in the way of best-laid plans. For example, you might get sick or injured or need to deal with a family issue or a financial crisis. Earlier in this section we considered a scenario in which a student realized she needed to change her major and her career plans. Such upsets, whether minor or major, may trigger a need to take some time off from school—perhaps a term or a year. Your priorities may shift. You may need to reevaluate goals.

Problem-Solving Strategies

Below is a simple list of four problem-solving strategies. They can be applied to any aspect of your life.

- What is the problem? Define it in detail. How is it affecting me and other people?

- How are other people dealing with this problem? Are they adjusting their time management skills? Can they still complete responsibilities, and on time?

- What is my range of possible solutions? Are solutions realistic? How might these solutions help me reach my goal/s?

- What do I need to do to implement solutions?

You may wish to also review the earlier set of questions about focusing with intention on goals.

Be confident that you can return to your intended path in time. Acknowledge the ways in which you need to regroup. Read inspiring words from people who have faced adversity and gained. Line up your resources, be resolved, and proceed with certainty toward your goals.

Setting goals can be a challenge, but working toward them, once you’ve set them, can be an even greater challenge—often because it implies that you will be making changes in your life. You might be creating new directions of thought or establishing new patterns of behavior, discarding old habits or starting new ones. Change will always be the lifeblood of achieving your goals.

You may find that as you navigate this path of change, one of your best resources is your social network. Your family, friends, roommates, coworkers, and others can help you maintain a steady focus on your goals. They can encourage and cheer you on, offer guidance when needed, share knowledge and wisdom they’ve gained, and possibly partner with you in working toward shared goals and ambitions. Your social network is a gold mine of support.

Here are some easy ways you can tap into goal-supporting “people power”:

- Make new friends

- Study with friends

- Actively engage with the college community

- Volunteer to help others

- Join student organizations

- Get an internship

- Work for a company related to your curriculum

- Stay connected via social media (but use it judiciously)*

- Keep a positive attitude

- Congratulate yourself on all you’ve done to get where you are

*A note about social media: More than 98 percent of college-age students use social media, says Experian Simmons. Twenty-seven percent of those students spent more than six hours a week on social media (UCLA, 2014). The University of Missouri, though, indicates in a 2015 study that this level of use may be problematic. It can lead to symptoms of envy, anxiety, and depression. Still, disconnecting from social media may have a negative impact, too, and further affect a student’s anxiety level.

Is there a healthy balance? If you feel overly attached to social media, you may find immediate and tangible benefit in cutting back. By tapering your use, your can devote more time to achieving your goals. You can also gain a sense of freedom and more excitement about working toward your goals.

SOURCES

- OpenNow College Success. Authored by Cengage Learning. Provided by: CEngage. Available at: https://oercommons.s3.amazonaws.com/media/editor/179572/CengageOpenNow_CollegeSuccessNarrative.pdf License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, available at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

- “Set Yourself Up for Success” from Effective Learning Strategies at Austin Community College. Authored by: Heather Syrett. Provided by: Austin Community College. Available at: https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/8434. License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

- College Success. Authored by: Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/sanjacinto-learningframework/chapter/classattendance/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike, available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/