Chapter 5: Deep Learning, Meta-Cognition, & Learning Preferences

Chapter 5: Deep Learning, Meta-Cognition, & Learning Preferences

Understanding the process of learning, memory, and your preferred learning style are all critical academic success factors. In this chapter, we will discuss how we learn, how memory works, and how you can identify your personal learning styles.

What is Thought?

“Cogito ergo sum.” This famous Latin phrase comes from French philosopher René Descartes in the early 1600s. Translated into English, it means “I think, therefore I am.” It’s actually a profound philosophical idea, and people have argued about it for centuries: we exist, and we are aware that we exist, because we think. Without thought or the ability to think, we don’t exist. Do you agree? Even if you think Descartes got it wrong, most would say that thought is intimately connected to being human and that, as humans, we are all thinking beings. What, then, are thinking and thought? Below are some basic working definitions:

- Thinking is the mental process you use to form associations and models of the world. When you think, you manipulate information to form concepts, to engage in problem-solving, to reason, and to make decisions.

- Thought can be described as the act of thinking that produces thoughts, which arise as ideas, images, sounds, or even emotions

Metacognition

Metacognition is one of the distinctive characteristics of the human mind that enables us to reflect on our own mental states. It is defined as “cognition about cognitive phenomena,” or “thinking about thinking.” Metacognition is reflected in many day-to-day activities, such as when you realize that one strategy is better than another for solving a particular type of problem, or when you are able to recognize how your own experiences and perspectives may impact how you understand, react to, or judge certain situations.

Metacognition includes two clusters of activities: knowledge about cognition and regulation of cognition. Metacognitive knowledge refers to a person’s knowledge or understanding of cognitive processes. In other words, it is the ability to think about what you know and how you know it. This includes knowledge about your own strengths and limitations as well as factors that may interact to help or hinder your learning. Metacognitive regulation builds on this knowledge and refers to a person’s ability to regulate cognitive processes during problem-solving. You use metacognitive knowledge to make decisions about how to approach new problems or how to effectively learn new information and skills. This involves using various self-regulatory mechanisms like planning ahead, monitoring your progress, and evaluating your own efficiency and effectiveness in learning a task. To give a concrete example of these metacognitive activities, let’s apply them to how you study for an exam. Knowing that your cell phone’s notifications tend to distract you from studying is an example of metacognitive knowledge: you are aware of your phone’s potential to hinder your learning. Metacognitive regulation requires you to take action based on this knowledge and would involve you making the conscious decision to put your cell phone where you cannot see or hear it or to turn it off completely, while you study. In doing so, you regulate your use of your phone to help yourself be more successful in preparing for your exam.

We said earlier that metacognitive knowledge involves thinking about the cognitive process, about what you know and how you know it. An important first step in developing metacognitive knowledge about yourself as a learner is to develop an awareness of how we learn new things. Consider experiences you’ve had with learning something new, such as learning to tie your shoes or drive a car. You probably began by showing interest in the process, and after some struggling, it became second nature. These experiences were all part of the learning process, which can be described in four stages:

1. Unconscious incompetence: This will likely be the easiest learning stage—you don’t know what you don’t know yet. During this stage, a learner mainly shows interest in something or prepares for learning. For example, if you wanted to learn how to dance, you might watch a video, talk to an instructor, or sign up for a future class. Stage 1 might not take long.

2. Conscious incompetence: This stage can be the most difficult for learners because you begin to register how much you need to learn—you know what you don’t know. This is metacognition at work! Think about the saying “It’s easier said than done.” In stage 1 the learner only has to discuss or show interest in a new experience, but in stage 2, he or she begins to apply new skills that contribute to reaching the learning goal. In the dance example above, you would now be learning basic dance steps. Successful completion of this stage relies on practice.

3. Conscious competence: You are beginning to master some parts of the learning goal and are feeling some confidence about what you do know. For example, you might now be able to complete basic dance steps with few mistakes and without your instructor reminding you how to do them. Stage 3 requires skill repetition, and metacognition helps you identify where to focus your efforts.

4. Unconscious competence: This is the final stage in which learners have successfully practiced and repeated the process they learned so many times that they can do it almost without thinking. At this point in your dancing, you might be able to apply your dance skills to a freestyle dance routine that you create yourself. However, to feel you are a “master” of a particular skill by the time you reach stage 4, you still need to practice constantly and reevaluate which stage you are in so you can keep learning. For example, if you now felt confident in basic dance skills and could perform your own dance routine, perhaps you’d want to explore other kinds of dance, such as tango or swing. That would return you to stage 1 or 2, but you might progress through the stages more quickly this time since you have already acquired some basic dance skills.

As a result of many amazing and potent research discoveries, the scientific community is learning a great deal about how plastic, malleable, and constantly changing the brain is. For example, the act of thinking—just thinking—can affect not only the way your brain works but also its physical shape and structure. While thinking is not a substitute for practice, you might be surprised to find how far it can get you. The following video explores some of these discoveries, which relate to all the thinking and thoughts involved in college success.

The following sections will help you to think more deeply and critically about your own thinking and learning. They will introduce you to some theories that help explain how people learn and how we can improve our learning. You will be able to think about your own learning in the context of these theories to identify your own strengths and areas where you can work to improve your learning process.

What are Learning Objectives?

What exactly are learning objectives? Learning objectives specify what someone will know, care about, or be able to do as a result of a learning experience. When your professor states a learning objective, it describes what you can expect to get out of a particular class, assignment, or reading.

Paying attention to learning objectives can help focus your attention on the most critical aspects of a learning experience. If you read the objectives closely, it can also help you determine how deeply you are expected to engage with the material. We will now look at Bloom’s taxonomy, which provides a framework for interpreting learning objectives.

Bloom's Taxonomy

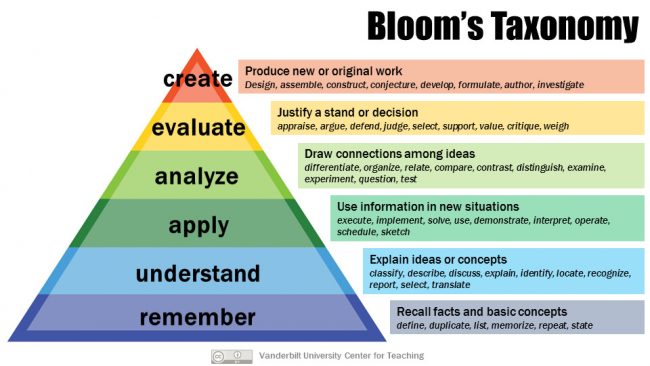

In 1956, Dr. Benjamin Bloom, an American educational psychologist who was particularly interested how people learn, chaired a committee of educators that developed and classified a set of learning objectives, which came to be known as Bloom’s taxonomy. This classification system has been updated a little since it was first developed, but it remains important for both students and teachers in helping to understand the skills and structures involved in learning.

Bloom’s taxonomy divides the cognitive domain of learning into six main learning-skill levels, or learning-skill stages, which are arranged hierarchically—moving from the simplest of functions like remembering and understanding, to more complex learning skills, like applying and analyzing, to the most complex skills—evaluating and creating. The lower levels are more straightforward and fundamental, and the higher levels are more sophisticated. See Figure 1, below.

"Bloom's Taxonomy" from Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Provided by Vanderbilt University, available at https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/ License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

The following table describes the six main skill sets within the cognitive domain and gives you information on the level of learning expected for each. Read each description closely for details of what college-level work looks like in each domain (note that the table begins with remembering, the lowest level of the taxonomy).

| MAIN SKILLS LEVELS WITHIN THE COGNITIVE DOMAIN | DESCRIPTION | EXAMPLES OF RELATED LEARNING SKILLS (specific actions related to the skill set) |

| REMEMBERING | When you are skilled in remembering, you can recognize or recall knowledge you’ve already gained, and you can use it to produce or retrieve definitions, facts, and lists. Remembering may be how you studied in grade school or high school, but college will require you to do more with the information. | identify · relate · list · define · recall · memorize · repeat · record · name |

| UNDERSTANDING | Understanding is the ability to grasp or construct meaning from oral, written, and graphic messages. Each college course will introduce you to new concepts, terms, processes, and functions. Once you gain a firm understanding of new information, you’ll find it easier to comprehend how or why something works. | restate · locate · report · recognize · explain · express · identify · discuss · describe · review · infer · illustrate · interpret · draw · represent · differentiate · conclude |

| APPLYING | When you apply, you use or implement learned material in new and concrete situations. In college you will be tested or assessed on what you’ve learned in the previous levels. You will be asked to solve problems in new situations by applying knowledge and skills in new ways. You may need to relate abstract ideas to practical situations. | apply · relate · develop · translate · use · operate · organize · employ · restructure · interpret · demonstrate · illustrate · practice · calculate · show · exhibit · dramatize |

| ANALYZING | When you analyze, you have the ability to break down or distinguish the parts of material into its components, so that its organizational structure may be better understood. At this level, you will have a clearer sense that you comprehend the content well. You will be able to answer questions such as what if, or why, or how something would work. | analyze · compare · probe · inquire · examine · contrast · categorize · differentiate · contrast · investigate · detect · survey · classify · deduce · experiment · scrutinize · discover · inspect · dissect · discriminate · separate |

| EVALUATING | With skills in evaluating, you are able to judge, check, and even critique the value of material for a given purpose. At this level in college you will be able to think critically, Your understanding of a concept or discipline will be profound. You may need to present and defend opinions. | judge · assess · compare · evaluate · conclude · measure · deduce · argue · decide · choose · rate · select · estimate · validate · consider · appraise · value · criticize · infer |

| CREATING | With skills in creating, you are able to put parts together to form a coherent or unique new whole. You can reorganize elements into a new pattern or structure through generating, planning, or producing. Creating requires originality and inventiveness. It brings together all levels of learning to theorize, design, and test new products, concepts, or functions. | compose · produce · design · assemble · create · prepare · predict · modify · plan · invent · formulate · collect · generalize · document combine · relate · propose · develop · arrange · construct · organize · originate · derive · write |

Reading and interpreting learning objectives is a metacognitive act, as the information can help you determine the level of learning expected of you and give you clues as to how you can prepare for assessment. For example, if your objective is to identify the parts of an atom, you should first recognize that being able to “identify” information falls within the domain of “remembering”; you will need to memorize the parts and be able to correctly label them. Flash cards, labeling a diagram, or drawing one yourself should be sufficient ways to prepare for your test. If, however, your objective is to calculate atomic mass, you will need to know not only the parts of the atom but also how to account for those parts to come up with the atomic mass; “calculate” falls within the domain of “applying,” which requires you to take information and use it to solve a problem in a new context.

Thinking comes naturally. You don’t have to make it happen—it just does. But you can make it happen in different ways. For example, you can think positively or negatively. You can think with “heart” and you can think with rational judgment. You can also think strategically and analytically, and mathematically and scientifically. These are a few of multiple ways in which the mind can process thought. To exercise metacognition is to think about your own thinking and cognitive processes. What are some forms of thinking you use? When do you use them, and why?

The theories of learning presented here will provide frameworks to help you make sense of all this thinking and act on it in ways that most effectively support your learning.

Model of Strategic Learning

The word “strategic” suggests the execution of a carefully planned strategy with the intent of achieving a specific goal. The model of strategic learning, as outlined by Claire Weinstein, provides a comprehensive framework for developing appropriate strategies for learning given the

unique conditions of each learner for any given learning experience. The model incorporates the learner’s skill, will, academic environment, and self-regulation:

- Skill refers to the learner’s content knowledge, self-awareness of strengths and weaknesses, and ability to employ effective skills such as goal-setting, active listening and reading, and note-taking.

- Will refers to the learner’s state of mind. This includes motivation, how you feel about learning (ranging from fear and anxiety to excitement and joy), beliefs about your abilities, and your level of commitment to personal goals.

- The academic environment encompasses factors that are external to the individual learner but still impact the learning process. Examples include access to academic support resources, the requirements of particular classes or assignments, teacher expectations, and the social context in which the learner lives.

- Finally, self-regulation is how the learner recognizes and manages each of these factors. To be strategic about learning, you may exert self-control in the form of time-management, emotional control, seeking assistance, and/or monitoring progress; a learner who does so is more likely to be successful than one who fails to self-regulate. Within this model, the learner is always at the center. Each learner is uniquely situated in terms of skill, will, and academic environment; it is also up to each learner to exercise self-regulation where possible to minimize or work around factors that interfere with learning and maximize those that support it.

Memory is an information processing system that we often compare to a computer. Memory is the set of processes used to encode, store, and retrieve information over different periods of time.

From "Memory Encoding". Authored by: Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wmopen-psychology/chapter/how-memory-functions/ . License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike, available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

Encoding involves the input of information into the memory system. Storage is the retention of the encoded information. Retrieval, or getting the information out of memory and back into awareness, is the third function.

Encoding

We get information into our brains through a process called encoding, which is the input of information into the memory system. Once we receive sensory information from the environment, our brains label or code it. We organize the information with other similar information and connect new concepts to existing concepts. Encoding information occurs through both automatic processing and effortful processing.

If someone asks you what you ate for lunch today, more than likely you could recall this information quite easily. This is known as automatic processing, or the encoding of details like time, space, frequency, and the meaning of words. Automatic processing is usually done without any conscious awareness. Recalling the last time you studied for a test is another example of automatic processing. But what about the actual test material you studied? It probably required a lot of work and attention on your part in order to encode that information. This is known as effortful processing.

When you first learn new skills such as driving a car, you have to put forth effort and attention to encode information about how to start a car, how to brake, how to handle a turn, and so on. Once you know how to drive, you can encode additional information about this skill automatically.

What are the most effective ways to ensure that important memories are well encoded? Even a simple sentence is easier to recall when it is meaningful (Anderson, 1984). Read the following sentences (Bransford & McCarrell, 1974), then look away and count backward from 30 by threes to zero, and then try to write down the sentences (no peeking back at this page!).

- The notes were sour because the seams split.

- The voyage wasn’t delayed because the bottle shattered.

- The haystack was important because the cloth ripped.

How well did you do? By themselves, the statements that you wrote down were most likely confusing and difficult for you to recall. Now, try writing them again, using the following prompts: bagpipe, ship christening, and parachutist. Next count backward from 40 by fours, then check yourself to see how well you recalled the sentences this time. You can see that the sentences are now much more memorable because each of the sentences was placed in context. The material is far better encoded when you make it meaningful.

There are three types of encoding. The encoding of words and their meaning is known as semantic encoding. It was first demonstrated by William Bousfield (1935) in an experiment in which he asked people to memorize words. The 60 words were actually divided into 4 categories of meaning, although the participants did not know this because the words were randomly presented. When they were asked to remember the words, they tended to recall them in categories, showing that they paid attention to the meanings of the words as they learned them.

Visual encoding is the encoding of images, and acoustic encoding is the encoding of sounds, words in particular. To see how visual encoding works, read over this list of words: car, level, dog, truth, book, value. If you were asked later to recall the words from this list, which ones do you think you’d most likely remember? You would probably have an easier time recalling the words car, dog, and book, and a more difficult time recalling the words level, truth, and value. Why? Because you can recall images (mental pictures) more easily than words alone. When you read the words car, dog, and book you created images of these things in your mind. These are concrete, high-imagery words. On the other hand, abstract words like level, truth, and value are low-imagery words. High-imagery words are encoded both visually and semantically (Paivio, 1986), thus building a stronger memory.

Now let’s turn our attention to acoustic encoding. You are driving in your car and a song comes on the radio that you haven’t heard in at least 10 years, but you sing along, recalling every word. In the United States, children often learn the alphabet through song, and they learn the number of days in each month through rhyme: “Thirty days hath September, / April, June, and November; / All the rest have thirty-one, / Save February, with twenty-eight days clear, / And twenty-nine each leap year.” These lessons are easy to remember because of acoustic encoding. We encode the sounds the words make. This is one of the reasons why much of what we teach young children is done through song, rhyme, and rhythm.

Which of the three types of encoding do you think would give you the best memory of verbal information? Some years ago, psychologists Fergus Craik and Endel Tulving (1975) conducted a series of experiments to find out. Participants were given words along with questions about them. The questions required the participants to process the words at one of the three levels. The visual processing questions included such things as asking the participants about the font of the letters. The acoustic processing questions asked the participants about the sound or rhyming of the words, and the semantic processing questions asked the participants about the meaning of the words. After the participants were presented with the words and questions, they were given an unexpected recall or recognition task.

Words that had been encoded semantically were better remembered than those encoded visually or acoustically. Semantic encoding involves a deeper level of processing than the shallower visual or acoustic encoding. Craik and Tulving concluded that we process verbal information best through semantic encoding, especially if we apply what is called the self-reference effect. The self-reference effect is the tendency for an individual to have better memory for information that relates to oneself in comparison to material that has less personal relevance ( according to Rogers, Kuiper & Kirker, 1977). Could semantic encoding be beneficial to you as you attempt to memorize the concepts in this chapter?

Storage

information and place it in storage. Storage is the creation of a permanent record of information.

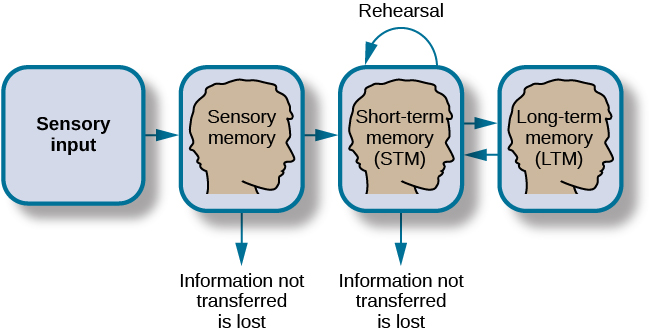

In order for a memory to go into storage (i.e., long-term memory), it has to pass through three distinct stages: Sensory Memory, Short-Term Memory, and finally Long-Term Memory. These stages were first proposed by Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin (1968). Their model of human memory, called Atkinson-Shiffrin (A-S), is based on the belief that we process memories in the same way that a computer processes information.

From "Storage". Authored by: Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wmopen-psychology/chapter/reading-storage/ . License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike, available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

According to the Atkinson-Shiffrin model of memory, information passes through three distinct stages in order for it to be stored in long-term memory.

Sensory Memory

In the Atkinson-Shiffrin model, stimuli from the environment are processed first in sensory memory: storage of brief sensory events, such as sights, sounds, and tastes. It is very brief storage—up to a couple of seconds. We are constantly bombarded with sensory information. We cannot absorb all of it, or even most of it. And most of it has no impact on our lives. For example, what was your professor wearing the last class period? As long as the professor was dressed appropriately, it does not really matter what she was wearing. Sensory information about sights, sounds, smells, and even textures, which we do not view as valuable information, we discard. If we view something as valuable, the information will move into our short-term memory system.

One study of sensory memory researched the significance of valuable information on short-term memory storage. J. R. Stroop discovered a memory phenomenon in the 1930s: you will name a color more easily if it appears printed in that color, which is called the Stroop effect. Try an experiment: name the colors of the words presented in the image below. Do not read the words, but say the color the word is printed in. For example, upon seeing the word “red” in green print, you should say “green,” not “red.” This experiment is fun, but it’s not as easy as it seems.

The Stroop effect describes why it is difficult for us to name a color when the word and the color of the word are different. Try it yourself below:

"Stroop Effect Test" provided by the University of Washington, available at: https://faculty.washington.edu/chudler/java/timestc.html

"Stroop Effect Test" provided by the University of Washington, available at: https://faculty.washington.edu/chudler/java/timestc.html

Short-Term Memory

Short-term memory is a temporary storage system that processes incoming sensory memory; sometimes it is called working memory. Short-term memory takes information from sensory memory and sometimes connects that memory to something already in long-term memory. Short-term memory storage lasts about 20 seconds. Think of short-term memory as the information you have displayed on your computer screen—a document, a spreadsheet, or a web page. Information in short-term memory either goes to long-term memory (when you save it to your hard drive) or it is discarded (when you delete a document or close a web browser).

You may find yourself asking, “How much information can our memory handle at once?” George Miller (1956), in his research on the capacity of memory, found that most people can retain about 7 items in short-term memory. Some remember 5, some 9, so he called the capacity of short-term memory the range of 7 items plus or minus 2. To explore the capacity and duration of your short-term memory, have a partner read the strings of random numbers below out loud to you, beginning each string by saying, “Ready?” and ending each by saying, “Recall,” at which point you should try to write down the string of numbers from memory.

Work through this series of numbers using the recall exercise explained above to determine the longest string of digits that you can store. Note the longest string at which you got the series correct. For most people, this will be close to 7, Miller’s famous 7 plus or minus 2. The recall is somewhat better for random numbers than for random letters (according to Jacobs, 1887), and also often slightly better for information we hear (acoustic encoding) rather than see (visual encoding) (according to Anderson, 1969).

| 9754 | 68259 | 913825 | 5963827 | 86951372 | 719384273 |

| 6419 | 67148 | 648327 | 5316842 | 51739826 | 163875942 |

Long-term Memory

Long-term memory is the continuous storage of information. Unlike short-term memory, the storage capacity of long-term memory has no limits. It encompasses all the things you can remember that happened more than just a few minutes ago to all of the things that you can remember that happened days, weeks, and years ago. In keeping with the computer analogy, the information in your long-term memory would be like the information you have saved on the hard drive. It isn’t there on your desktop (your short-term memory), but you can pull up this information when you want it, at least most of the time. Not all long-term memories are strong memories. Some memories can only be recalled through prompts. For example, you might easily recall a fact— “What is the capital of the United States?”—or a procedure—“How do you ride a bike?”—but you might struggle to recall the name of the restaurant you had dinner when you were on vacation in France last summer. A prompt, such as that the restaurant was named after its owner, who spoke to you about your shared interest in soccer, may help you recall the name of the restaurant

Retrieval

So you have worked hard to encode (via effortful processing) and store some important information for your upcoming final exam. How do you get that information back out of storage when you need it? The act of getting information out of memory storage and back into conscious awareness is known as retrieval. This would be similar to finding and opening a paper you had previously saved on your computer’s hard drive. Now it’s back on your desktop, and you can work with it again. Our ability to retrieve information from long-term memory is vital to our everyday functioning. You must be able to retrieve information from memory in order to do everything from knowing how to brush your hair and teeth, to driving to work, to knowing how to perform your job once you get there.

There are three ways you can retrieve information out of your long-term memory storage system: recall, recognition, and relearning. Recall is what we most often think about when we talk about memory retrieval: it means you can access information without cues. For example, you would use recall for an essay test. Recognition happens when you identify information that you have previously learned after encountering it again. It involves a process of comparison. When you take a multiple-choice test, you are relying on recognition to help you choose the correct answer. Here is another example. Let’s say you graduated from high school 10 years ago, and you have returned to your hometown for your 10-year reunion. You may not be able to recall all of your classmates, but you recognize many of them based on their yearbook photos.

The third form of retrieval is relearning, and it’s just what it sounds like. It involves learning information that you previously learned. Whitney took Spanish in high school, but after high school, she did not have the opportunity to speak Spanish. Whitney is now 31, and her company has offered her an opportunity to work in their Mexico City office. In order to prepare herself, she enrolls in a Spanish course at the local community center. She’s surprised at how quickly she’s able to pick up the language after not speaking it for 13 years; this is an example of relearning.

Forgetting

As we just learned, your brain must do some work (effortful processing) to encode information and move it into short-term, and ultimately long-term memory. This has strong implications for you as a student, as it can impact your learning – if you do not do the work to encode and store information, you are likely to forget it altogether.

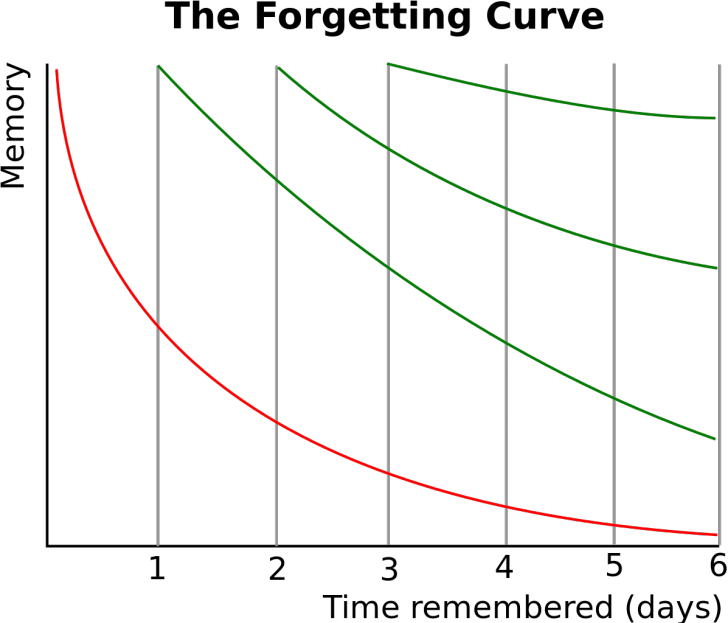

The forgetting curve hypothesizes the decline of memory retention over time. This curve shows how information is lost over time when there is no attempt to retain it.

In 1885, German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus hypothesized that the rate of forgetting is exponential. Using himself as the sole subject in his experiment, he memorized lists of three-letter nonsense syllable words—two consonants and one vowel in the middle. He then measured his own capacity to relearn a given list of words after a variety of given time period. He found that forgetting occurs in a systematic manner, beginning rapidly and then leveling off, represented graphically in the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve. From this research, Ebbinghaus concluded that much of what we forget is lost soon after it is originally learned, but that the amount of forgetting eventually levels off. Research indicates that people forget 80 percent of what they learn only a day later. This statistic may not sound very encouraging, given all that you’re expected to learn and remember as a college student. Really, though, it points to the importance of a study strategy other than waiting until the night before a final exam to review a semester’s worth of readings and notes. When you learn something new, the goal is to “lock it in” sooner rather than later and move it from short-term memory to long-term memory, where it can be accessed when you need it (like at the end of the semester for your final exam or maybe years from now). The next section will explore a variety of strategies you can use to process information more deeply and help improve recall.

"Forgetting Curve" from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forgetting_curve

Jennifer felt anxious about an upcoming history exam. This would be her first test in a college class, and she wanted to do well. Jennifer took lots of notes during class and while reading the textbook. In preparation for the exam, she tried to review all five textbook chapters along with all of her notes. The morning of the exam, Jennifer felt nervous and unprepared. After so much studying and review, why wasn’t she more confident?

Jennifer’s situation shows that there really is such a thing as studying too much. Her mistake was in trying to master all of the course material. Whether you take one or more than one class, it’s simply impossible to retain every single particle of information you encounter in a textbook or lecture. And, instructors don’t generally give open-book exams or allow their students to preview the quizzes or tests ahead of time. So, how can you decide what to study and “know what to know”? The answer is to prioritize what you’re trying to learn and memorize, rather than trying to tackle all of it. Below are some strategies to help you do this.

- Think about concepts rather than facts: From time to time, you’ll need to memorize cold, hard facts—like a list of math equations or a vocabulary list in a Spanish class. Most of the time, though, instructors will care much more that you are learning about the key concepts in a subject or course—such as how photosynthesis works, how to write a thesis statement, the causes of the French Revolution, and so on. Jennifer, from the scenario above, might have been more successful with her studying—and felt better about it—if she had focused on the important historical developments (the “big ideas”) discussed in class, as opposed to trying to memorize a long list of dates and facts.

- Take cues from your instructor: Pay attention to what your instructor writes on the board or includes in study guides and handouts. Although these may be short—perhaps just a list of words and phrases—they are likely core concepts that you’ll want to focus on. Also, instructors tend to refer to important concepts repeatedly during class, and they may even tell you what’s important to know before an exam or other assessment.

- Look for key terms: Textbooks will often put key terms in bold or italics. These terms and their definitions are usually important and can help you remember larger concepts.

- Use summaries: Textbooks often have summaries or study guides at the end of each chapter. These summaries are a good way to check in and see whether you grasp the main elements of the reading (each chapter of this text, for example, ends with a set of “key takeaways” that reiterate the most important concepts). If no summary is available, try to write your own—you’ll learn much more by writing about what you read than by reading alone

In the previous discussion of how memory works, the importance of making intentional efforts to transfer information from short-term to long-term memory was noted. Below are some strategies to facilitate this process:

- Start reviewing new material immediately: Remember that people typically forget a significant amount of new information within 24 hours of learning it. As a student, you can benefit from starting to study new material right away. If you’re introduced to new concepts in class, for example, don’t wait a few days, or until the test is coming up, to start reviewing your notes and doing the related reading assignment. The sooner the better! Studying notes and writing questions or comments about what you learned right after class can help keep new information fresh in your mind.

- Study frequently for shorter periods of time: Once information becomes a part of long-term memory, you’re more likely to remember it. If you want to improve the odds of recalling course material by the time of an exam or in a future class, try reviewing it a little bit every day. Building up your knowledge and recall this way can also help you avoid needing to “cram” and feeling overwhelmed by everything you may have forgotten. Strengthening Your Memory We’ve discussed the importance of zeroing in on the main concepts you learn in class and of transferring them from short-term to long-term memory. But how can you work to strengthen your overall memory? Some people have stronger memories than others, but memorizing new information takes work for anyone. Below are some strategies that can aid memory.

We’ve discussed the importance of zeroing in on the main concepts you learn in class and of transferring them from short-term to long-term memory. But how can you work to strengthen your overall memory? Some people have stronger memories than others, but memorizing new information takes work for anyone. Below are some strategies that can aid memory.

Rehearsal

One strategy is rehearsal, or the conscious repetition of information to be remembered (Craik & Watkins, 1973). This strategy is linked to studying material frequently for shorter periods of time. You may not remember when or how you learned skills like riding a bike or tying your shoes. Mastery came with practice, and at some point the skills became second nature. Academic learning is no different: if you spend enough time with important course concepts and practice them often, you will know them in the same way you know how to ride a bike, almost without thinking about them. For example, think about how you learned your multiplication tables. You may recall that 6 x 6 = 36, 6 x 7 = 42, and 6 x 8 = 48. Memorizing these facts is rehearsal.

Incorporate visuals

Visual aids like note cards, concept maps, and highlighted text are ways of making information stand out. Because they are shorter and more concise, they have the advantage of making the information to be memorized seem more manageable and less daunting (than an entire textbook chapter, for example). Some students write key terms on note cards and hang them around their desk or mirror so that they routinely see them and study them without even trying.

Create mnemonics

Memory devices known as mnemonics can help you retain information while only needing to remember a unique phrase or letter pattern that stands out. Mnemonic devices are memory aids that help us organize information for encoding. They are especially useful when we want to recall larger bits of information such as steps, stages, phases, and parts of a system (Bellezza, 1981).

There are different types of mnemonic devices, such as the acronym. An acronym is a word formed by the first letter of each of the words you want to remember. For example, even if you live near one, you might have difficulty recalling the names of all five Great Lakes. What if I told you to think of the word Homes? HOMES is an acronym that represents Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, and Superior: the five Great Lakes.

Another type of mnemonic device is an acrostic: You make a phrase of all the first letters of the words. For example, if you are taking a math test and you are having difficulty remembering the order of operations, recalling the sentence “Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally” will help you, because the order of mathematical operations is Parentheses, Exponents, Multiplication, Division, Addition, Subtraction. There also are jingles, which are rhyming tunes that contain keywords related to the concept, such as “i before e, except after c.” You might use a mnemonic device to help you remember someone’s name, a mathematical formula, or the six levels of Bloom’s taxonomy.

Chunking

Another strategy is chunking, where you organize information into manageable bits or chunks (Bodie, Powers, & Fitch-Hauser, 2006). Chunking is useful when trying to remember information like dates and phone numbers. Instead of trying to remember 5205550467, you remember the number as 520-555-0467. So, if you met an interesting person at a party and you wanted to remember his phone number, you would naturally chunk it, and you could repeat the number over and over, combining the strategies of chunking and rehearsal.

Connect new information to old information

Take stock of what you already know—information that’s already stored in long-term memory—and use it as a foundation for learning newer information. It’s easier to remember new information if you can connect it to old information or to a familiar frame of reference. For example, if you are taking a sociology class and are learning about different types of social groups, you may be able to think of examples from your own experience that relates to the different types.

Get quality sleep

Although some people require more or less sleep than the recommended amount, most people should aim for six to eight hours every night. School puts a lot of demands on the brain, and, like tired muscles after a long workout, your brain needs to rest after being exercised and taking in all sorts of new information during the day. Plus, while you are sleeping, your brain is still at work. During sleep, the brain organizes and consolidates information to be stored in long-term memory (Abel & Bäuml, 2013). A good night’s rest can help you remember more and feel prepared for learning the next day.

Kyle was excited to take a beginning Spanish class to prepare for a semester abroad in Spain. Before his first vocabulary quiz, he reviewed his notes many times. Kyle took the quiz, but when he got the results, he was surprised to see that he had earned a B-, despite having studied so much. Kyle’s professor suggested that he experiment with different ways of studying. For example, in addition to studying his written notes, he might also try listening to audio recordings of the vocabulary words and repeating them out loud.

Many of us, like Kyle, are accustomed to very traditional learning styles as a result of our experience as K–12 students. For instance, we can all remember listening to a teacher talk and copying notes off the chalkboard. However, when it comes to learning, one size doesn’t fit all. People have different learning strengths, styles, and preferences, and these can vary from subject to subject. For example, while Kyle might prefer listening to recordings to help him learn Spanish, he might prefer hands-on activities like labs to master the concepts in his biology course. This chapter will explore some theories that take into account these different approaches to learning.

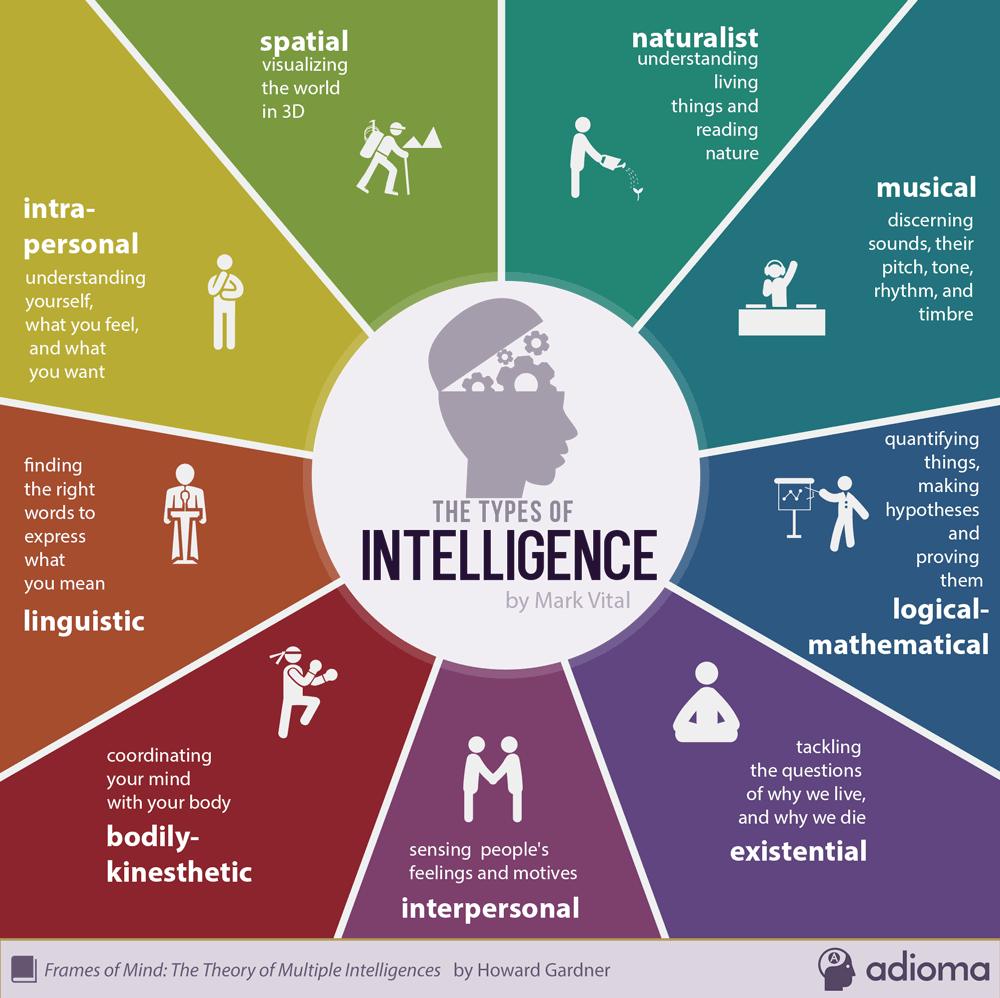

For nearly a century, educators and psychologists have debated the nature of intelligence, and more specifically whether intelligence is just one broad ability or can take more than one form. Many classical definitions of the concept have tended to define intelligence as a single broad ability that allows a person to solve or complete many sorts of tasks, or at least many academic tasks like reading, knowledge of vocabulary, and the solving of logical problems.

One of the most prominent of these models to portray intelligence as having multiple forms is Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences. Gardner proposes that there are eight different forms of intelligence, each of which functions independently of the others. Each person has a mix of all eight abilities—more of some and less of others—that helps to constitute that person’s individual cognitive profile. These eight intelligences are summarized in the table below. Since most tasks—including most tasks in classrooms—require several forms of intelligence and can be completed in more than one way, it is possible for people with various profiles of talents to succeed on a task equally well. In writing an essay, for example, a student with high interpersonal intelligence but rather average verbal intelligence might use her interpersonal strength to get a lot of help and advice from classmates and the teacher. A student with the opposite profile might work well on his own but without the benefit of help from others. Both students might end up with essays that are good, but good for different reasons.

This model can be useful as a way for students to think about how you approach your learning. Multiple intelligences suggest that there is (or may be) more than one way to be “smart,” and that you can benefit from identifying your personal strengths and preferences.

Learning styles are also called learning modalities. Neil Fleming’s VARK model proposes four learning modalities, which relate learning to the senses:

- Visual learning

- Auditory learning

- Read/write learning

- Kinesthetic learning

Fleming claimed that visual learners have a preference for seeing information represented through visual aids that use methods other than words, such as graphs, charts, diagrams, and symbols. Auditory learners best learn by listening (lectures, discussions, tapes, etc.). Read/write learners have a preference for written words and gravitate toward readings, dictionaries, reference works, and research. Tactile/kinesthetic learners prefer to learn via experience—moving, touching, and doing (active exploration of the world, science projects, experiments, etc.). Additional examples of these modalities are shown in the table below.

Sensory Learning Styles and Examples:

Visual | Auditory | Reading/Writing | Kinesthetic |

picture · shape · sculpture · painting | listening · rhythms · tones · beats | books · articles · research · take notes | gestures · body movements · object manipulation · positioning |

The VARK model can be a helpful way of thinking about different learning styles and preferences, but they are certainly not the last word on how people learn or prefer to learn. Many educators consider the distinctions useful, finding that students benefit from having access to a blend of learning approaches. Others find the idea of three or four “styles” to be distracting or limiting.

Multimodal Learning

In the college setting, you’ll probably discover that instructors teach their course materials according to the method they think will be most effective for all students. Thus, regardless of your individual learning preference, you will probably be asked to engage in all types of learning. For instance, even if you consider yourself to be a “visual learner,” you will still probably have to write papers in some of your classes. Research suggests that it’s good for the brain to learn in new ways and that learning in different modalities can help learners become more well-rounded.

Consider the following statistics on how much content students absorb through different learning methods:

- 10 percent of content they read

- 20 percent of content they hear

- 30 percent of content they visualize

- 50 percent of what they both visualize and hear

- 70 percent of what they say

- 90 percent of what they say and do

The range of these results underscores the importance of mixing up the ways in which you study and engage with learning materials.

Through completing the multiple intelligences and learning styles activities, you have likely discovered that you have multiple strengths and preferences. Applying more than one approach is known as multimodal learning. This strategy is useful not only for students who prefer to combine learning styles and intelligences but also for those who may not know which works best for them. It’s also a good way to mix things up and keep learning fun.

For example, consider how you might combine visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learning styles to a biology class. For visual learning, you could create flashcards containing images of individual animals and the species name. For auditory learning, you could have a friend quiz you on the flashcards. For kinesthetic learning, you could move the flash cards around on a board to show a food web (food chain).

SOURCES

- Active Listening in the Classroom” from Effective Learning Strategies at Austin Community College. Authored by: Heather Syrett. Provided by: Austin Community College. Available at: https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/8434. License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

- “Personal Learning Preferences” from Effective Learning Strategies at Austin Community College. Authored by: Laura Lucas. Provided by: Austin Community College. Available at: https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/8434. License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

- “Theories of Learning” from Effective Learning Strategies at Austin Community College. Authored by: Laura Lucas. Provided by: Austin Community College. Available at: https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/8434. License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

- College Success. Authored by: Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/sanjacinto-learningframework/chapter/classattendance/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike, available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

- OpenNow College Success. Authored by Cengage Learning. Provided by: CEngage. Available at: https://oercommons.s3.amazonaws.com/media/editor/179572/CengageOpenNow_CollegeSuccessNarrative.pdf License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, available at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

- The Learning Cycle and Learning Styles (Monroe Community College). Provided by: Lumen Learning Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/collegesuccess2x30master/chapter/participating-inclass/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike.

- Patterns of Thought. Provided by: Lumen Learning Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/collegesuccesslumen/chapter/patterns-of-thought/ . License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike.

- The Learning Process. Provided by: Lumen Learning Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/collegesuccesslumen/chapter/the-learning-process/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike.

- Creative Thinking Skills. Provided by: Lumen Learning Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/collegesuccesslumen/chapter/creative-thinking-skills/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike.

- Meta-Cognition in Mindfulness: A Conceptual Analysis. Authored by: Dilwar Hussain. Provided by: Psychological Thought. Located at: http://psyct.psychopen.eu/article/view/139/html. License: CC BY: Attribution, available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

- Emotional Intelligence. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emotional_intelligence. License: CC BY-SA: AttributionShareAlike, available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

- Three Aspects of Successful Intelligence. Authored by: Mary Frangie. Provided by: Critical and Creative Thinking Graduate Program, University of Massachusetts Boston. Located at: http://cct.wikispaces.umb.edu/Three+Aspects+of+Successful+Intelligence. License: CC BY: Attribution, , available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/